As China pushes deeper into space, exploring and even seeking to control territory on the moon, the Pentagon and Congress must move quickly to ensure freedom of operations in cislunar space—or risk ceding the the vast expanse between geosynchronous orbit and the moon to a rival, officials and experts say.

“Failure to act now will limit future options, create an unsustainable precedent in the cislunar environment, or even surrender U.S. leadership in space and weaken U.S. leadership globally,” warned retired Space Force Col. Charles Galbreath, senior resident fellow at the Mitchell Institute, in a new paper, “Securing Cislunar Space and the First Island Chain Off the Coast of Earth.”

Equating cislunar space and the Moon to the first and second island chains in the waters around China, Galbreath sees the competition for advantage in the cislunar regime as akin to naval competition in the age of exploration.

Even definitions are beginning to change. For years, “deep space” in the U.S. military context meant geosynchronous orbit (GEO), the zone about 36,000 miles from the Earth’s surface where the biggest and most expensive U.S. space assets operate, said Joel B. Mozer, former director of science, technology, and research for the Space Force, during a rollout event for Galbreath’s paper.

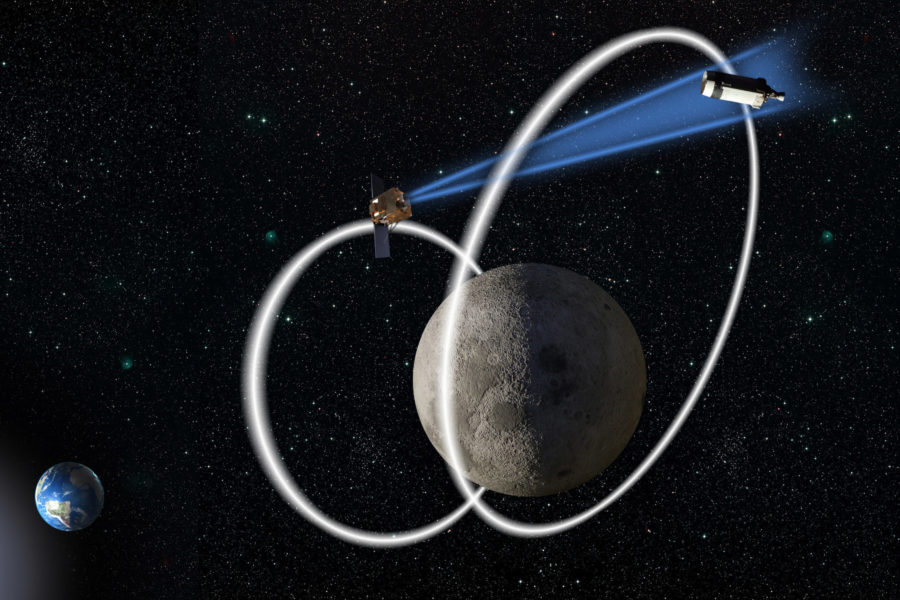

Now, however, the complex region is getting more attention. The Air Force Research Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate co-published a “primer” on cislunar space in 2021, laying out in clear terms the unique challenges of the region. Those challenges begin with its sheer expanse—equivalent, Mozer said, to “280,000 Earths”—and the challenging orbital dynamics that occur as objects get further from Earth and closer to the moon. Once far enough away to be affected by the gravitational pulls of both the Moon and the Earth, orbits change rapidly and become far harder to calculate and predict.

Driving interest in deep space are the many of the same factors as were in play at the dawn of the age of terrestrial exploration: potential scientific and economic interests. Both the U.S. and China have begun to amass allies in this new space race, and activities in cislunar space are expected to ramp up rapidly in the 2030s and beyond.

Galbreath argues the next few years are crucial. “Given a lack of established international norms, this will be just like any other era of territorial exploration and expansion—those who arrive first set the terms,” he wrote. Galbreath stressed during the rollout that he is not advocating for placing weapons in cislunar space, which could violate the Outer Space Treaty, which was designed to ensure peaceful space exploration. But he and others say China’s ambitions and the historical record are proof that the U.S. must be prepared.

“Human history says that when humanity goes to uncharted places and starts to interact with each other, that the need for defense has followed,” said then-Lt. Gen. Stephen N. Whiting at the Spacepower conference in Orlando, Fla., in December. “And as the economy moves out to new places like the moon, asteroids, Mars, you [may] need a military, just like when the countries of old would find a new uncharted place and start to develop the resources there needed a navy to protect that. That day is coming.”

Galbreath cited Ye Peijian, the head of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, who in 2015 compared the moon and Mars to the disputed islands in the East and South China Seas.

“The universe is an ocean, the moon is the Diaoyu Islands, Mars is Huangyan Island,” Peijan said then. “If we don’t go there now even though we’re capable of doing so, then we will be blamed by our descendants. If others go there, then they will take over, and you won’t be able to go even if you want to. This is reason enough.”

Such comments, Galbreath said, “invite comparison to the gray zone tactics demonstrated by China in pursuit of their self-interested goals and actions directed in isolation through their authoritarian regime, such as covert weaponization, territorial claims, coercion, and other aggressive behavior—conduct they have repeatedly and increasingly displayed in the Western Pacific.”

In response, the U.S. Space Force and Space Command should build out the infrastructures necessary to monitor and, if necessary, respond to threats in cislunar space, Galbreath recommended.

Already the Pentagon has started, establishing the 19th Space Defense Squadron to lead space domain awareness in cislunar and extra-geosynchronous areas, and also developing Oracle, an AFRL satellite for tracking objects in cislunar space, which is projected to launch in 2026. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has also funded a study on the lunar economy.

More is needed, and quickly, Galbreath argues. “An immediate, modest additive investment by Congress to the Space Force over the next five years will have a profound and lasting impact on the stability of new areas of space exploration, starting in the cislunar regime but extending further into the solar system,” he wrote. “This is a foundational era, and the U.S. must engage appropriately.”

Galbreath says a nominal investment of $250 million per year in new funding over the next five years, plus 200 Guardians focused on the mission, will accelerate U.S. understanding, capability, and capacity, and could stimulate further commercial development.

“Given that the United States is competing with adversaries in this domain, failure to act now will result in a capability gap,” he writes. “The initial efforts of AFRL and DARPA are excellent starts, but more needs to be done. This demands additive funding.”

Galbreath recommended that the Space Force and U.S. Space Command:

- Develop cislunar experts

- Establish doctrine, concepts of operations, and requirements to accelerate the race to the Moon and secure interests there

- Work with AFRL and DARPA to invest in cislunar research

- Invest to transition researchinto operational capabilities.