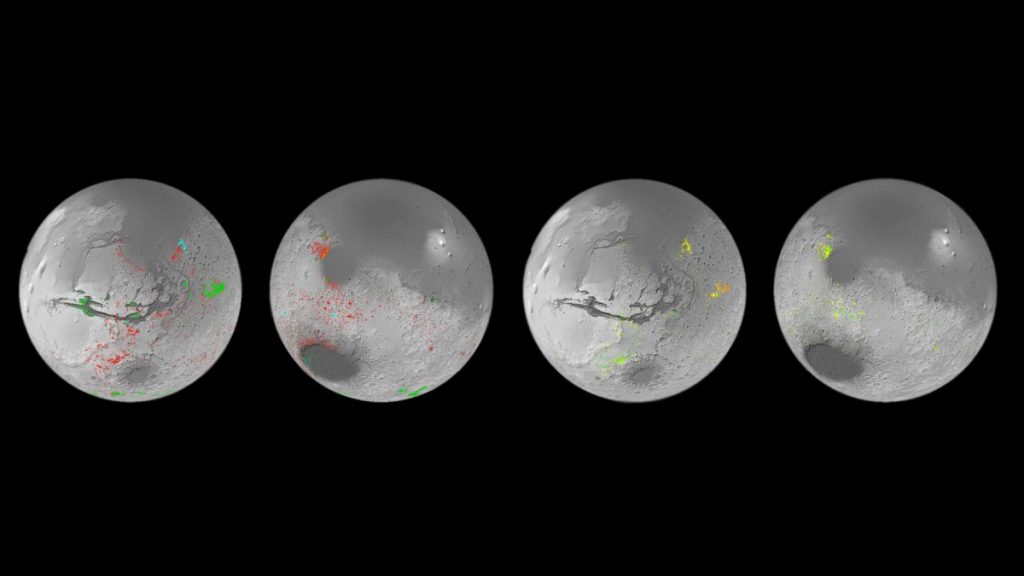

A new map of mineral deposits on Mars could not only change our understanding of past water distribution on the Red Planet but also help create a roadmap for future Mars exploration — including crewed missions.

The new map has revealed an unexpected abundance of minerals created by the interaction of rock and water, with hundreds of thousands formerly water-rich areas discovered in some of Mars‘ most ancient regions.

The map could lead to a more detailed investigation of Martian geology that could reveal what happened when Mars changed from a planet quite like Earth to the dry and arid world we see today, and whether the planet was ever capable of supporting life.

“I think we have collectively oversimplified Mars,” John Carter, assistant professor of planetary science at Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Paris-Saclay University, who was part of the team behind the map , said in a statement. (opens in new tab) “The evolution from lots of water to no water is not as clear cut as we thought, the water didn’t just stop overnight.”

Related: Mars was always too small to hold onto its oceans, rivers and lakes

Carter also explained that Mars’ more complex geology may be more similar to that of our planet than previously thought.

“We see a huge diversity of geological contexts so that no one process or simple timeline can explain the evolution of the mineralogy of Mars,” the researcher continued. “If you exclude life processes on Earth, Mars exhibits a diversity of mineralogy in geological settings just as Earth does.”

The map has been created using over a decade worth of data collected by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) OMEGA (Mars Express Observatoire pour la Mineralogie, l’Eau, les Glaces et l’Activité) instrument on the Mars Express spacecraft, and the CRISM (Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars) instrument on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Of particular interest on the map are the traces of water-rich minerals and rocks that were changed into clays and salts through interactions with water in the Red Planet’s distant past.

Revealing Mars’ complex geological past

Different water-rich clays and minerals are created when water interacts with rocks in a variety of conditions.

When small amounts of water interact with volcanic rock, clay minerals such as smectite and vermiculite form. These retain many of the same chemical elements — particularly iron and magnesium — as the volcanic rocks that birthed them.

When large amounts of water interact with rocks, however, the clays that are formed are less like the progenitor rocks as soluble elements are washed away. This leaves aluminum-rich clays like kaolin in their wake.

Up to a decade ago, researchers were only aware of around 1,000 such clay-rich outcrops on Mars. This meant aqueous clays were considered geological oddities and suggested that there were limitations to how much water had been on Mars in the past and for how long it had been preserved.

The new map shows that, surprisingly, these minerals are more prevalent than scientists thought, indicating that water played a much bigger role in shaping the geology of Mars.

“This work has now established that when you are studying the ancient terrains in detail, not seeing these minerals is actually the oddity,” Carter added.

Not only do these results suggest that water was prevalent and important in shaping Mars, but that the formation of clays and salts on the Red Planet is more complicated than previously suspected.

In the past scientists thought that just a few clay types were formed when Mars was in its wet period — estimated to have been as long as 4 billion years ago — and when the water dried up, the planet transitioned to the dry and arid world we see today, and salts were left behind.

The newly created map shows that while salts did form after clays in many areas, in some locations across the Martian surface there is a mixing of salts and clays, and there are also salts that predate the production of clay.

Planning for future Mars missions

The team behind the Mars mineral map didn’t stop at the basic detection of minerals. They also quantified the concentrations of these aqueous minerals present in a variety of locations.

Because these minerals still contain water molecules, they could be used by future crewed missions to extract water for both astronauts and for the production of fuel, lightening the load future space missions need to haul to the Red Planet as well as the cost of such missions.

The clays and salts could even be utilized as building materials to establish bases and other facilities on the Martian surface.

Even before crewed missions head to Mars, areas rich in aqueous minerals could prove excellent locations for robotic Mars missions to conduct geological research.

As a prime example of this, the Oxia Planum — a clay-rich site discovered during the creation of this map — has been suggested as a potential landing site for the ESA-operated Rosalind Franklin rover.

“If we know where, and in which percentage each mineral is present, it gives us a better idea of how those minerals could have been formed,” Lucie Riu, an ESA research fellow and co-author of the study, said in the statement. “This is what I am interested in, and I think this kind of mapping work will help open up those studies going forward.”

Two papers (opens in new tab) detailing the creation of this new Mars map are published in the journal Icarus. (opens in new tab)

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.