Pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell is the star of a kid’s book using an ancient language she happened to know: Latin.

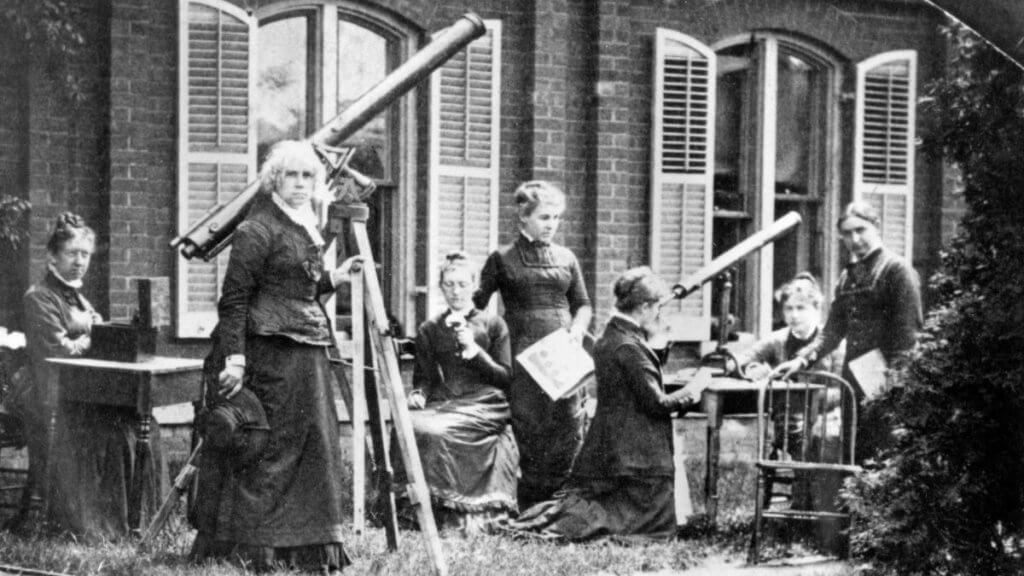

Massachusetts-born Maria Mitchell (1818-1889) is best known for discovering a comet in 1847 and working to inspire women astronomers as a professor of astronomy at Vassar College, which she joined in 1865. Some 205 years after her birth, Mitchell continues to inspire as the first U.S. woman astronomer.

Her legacy inspired Rachel Beth Cunning, a Latin and English as a second language teacher, to take on the challenge of making a children’s science book — a journey that brought Cunning back to her childhood, when she subscribed to astronomy magazines and read about the stars. Her Latin-language book is called Astronomia: Fabula Planetarium (Astronomy: Stories of the Planets; Bombax Press, 2022), and you can buy it on Amazon (opens in new tab).

Related: 20 trailblazing women in astronomy and astrophysics

“One of the things that I am generally very interested in — as someone who loves history and who loves nerdy science things and who loves literature and languages — is all the voices that get lost through time,” Cunning told Space.com in an interview earlier in March, which is Women’s History Month.

“There are a lot of voices that get lost,” Cunning continued, “and unfortunately, they tend to be women’s voices.”

Latin was the language of ancient Rome and, for a time, much of the world the imperialist ancients conquered; Latin then continued for centuries afterward as the primary language of the Christian church.

Much of the existing Latin literature today is male, but a precious minority of writing is female and receiving more scholar attention. It is thought that female voices were lost over the ages due not only to a lack of literacy or time to write, but also because the medieval preservationists who rewrote fading ancient manuscripts in what we now call Europe and the Middle East were not as inclined to include female voices.

Mitchell was fluent enough to read Latin-language science books (opens in new tab) in her childhood, which was not unusual in the 19th century; today, however, Latin’s schooling role has shifted considerably.

Latin’s descendants live on today in languages like French, Spanish and Portuguese (as well as English, given that the language began borrowing heavily from French after the Norman Conquest). But Latin is barely taught in schools or universities any more. That said, there is a growing “living Latin” movement of YouTubers, novella writers and teachers who use Latin in classes as a spoken language, rather than a grammar puzzle. That’s where the book about Mitchell comes in.

Related: Do we need a single international language in space?

(opens in new tab)

Cunning paid tribute to numerous educators who came before her and endeavored to make Latin more adaptable to the modern day. She herself found clever translations for “spaceship” and other modern technical terms in Latin, thanks to research in the community.

The story is meant to motivate young Latin learners to keep striving for their interests in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), Cunning said, through the example that Mitchell herself set during an era when women couldn’t even vote.

“You see this baller woman, advocating for education and the importance of education, and her role in helping other women have access to education. She’s really cool, and then she also did so much for just so many different groups,” Cunning said, pointing particularly to Mitchell’s Vassar College days.

Related: How women and the moon intertwine in literature

Cunning added that she wants to help expand the available Latin-language literature out there and to keep writing novellas from a female perspective, or, at the least, to include female voices. Some of her other Latin-language works (opens in new tab) include the myths of Cupid and Psyche, along with a fictional tale of a young girl living in Pompeii.

These female voices are needed for students, Cunning emphasized. “I want them to feel that they’re part of a long line of history, because they are part of a long group of women who are wonderful and smart and funny, who have made amazing contributions to science, the world and our understanding of it. That’s what I have often felt like was missing from my own education, is feeling that sense of continuity.”

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of “Why Am I Taller (opens in new tab)?” (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).