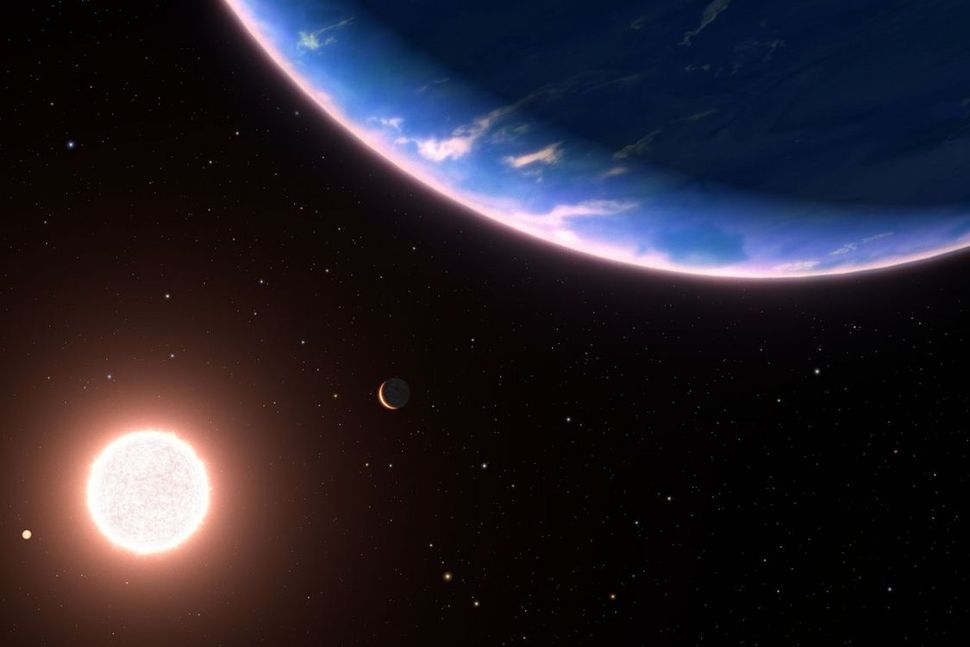

A nearby alien planet is the first of its kind, new observations by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) suggest.

Located around 100 light-years away from Earth, the exoplanet is shrouded in a thick envelope of steam. This world, designated GJ 9827 d, is around twice the size of Earth, three times more massive than our planet, and has an atmosphere almost entirely composed of water vapor.

“This is the first time we’re ever seeing something like this,” team member and former University of Michigan undergraduate student Eshan Raul, currently at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said in a statement. “The planet appears to be made mostly of hot water vapor, making it something we’re calling a ‘steam world.’ To be clear, this planet isn’t hospitable to at least the types of life that we’re familiar with on Earth.”

Astronomers have long speculated that “steam worlds” like GJ 9827 d could exist, but this is the first time such an exoplanet has been observed.

As Raul points out, this planet is unlikely to support life, at least as we understand it, but it could help astronomers study other small exoplanets between the size of Earth and Neptune that are habitable.

Related: NASA’s exoplanet hunter TESS spots a record-breaking 3-star system

I see right through you!

The study team, led by Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb from the University of Montréal’s Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets, discovered GJ 9827 d’s steamy nature using a technique called “transmission spectroscopy.”

Transmission spectroscopy is based on the fact that elements and the chemicals they make up absorb and emit light at characteristic electromagnetic wavelengths. When light from a star shines through the atmosphere of a planet, the elements in that atmosphere absorb certain wavelengths, leaving “gaps” in the light spectrum. These gaps are the “fingerprints” of specific elements and molecules in that atmosphere.

Thus far, the majority of exoplanets that astronomers have investigated using this method have possessed atmospheres dominated by the universe’s two lightest and most common elements, hydrogen and helium. That is similar to the atmospheres of the solar system gas giants Jupiter and Saturn but markedly different from the complex atmosphere of Earth and from the atmospheres that would be needed to support life as we know it.

“GJ 9827 d is the first planet where we detect an atmosphere rich in heavy molecules like the terrestrial planets of the solar system,” Piaulet-Ghorayeb said in the statement. “This is a huge step.”

GJ 9827 d was first discovered by the Kepler space telescope in 2017. The exoplanet is located just 5.2 million miles (8.4 million kilometers) from its host star, GJ 9827, which is around 6% of the distance between Earth and the sun. That proximity means GJ 9827 d completes an orbit in just over six Earth days. It is the third of three known exoplanets found around this star.

In 2023, the Hubble Space Telescope found the first tantalizing hints of water vapor in the atmosphere of GJ 9827 d. The sensitivity of JWST and its Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) instrument allowed the study team to discover that this exoplanet doesn’t just have hints of water vapor; it is metaphorically drowning in it!

“It was a very surreal moment,” said Raul. “We were searching specifically for water worlds because it was hypothesized that they could exist. If these are real, it really makes you wonder what else could be out there.”

The team thinks there are many more worlds like GJ 9827 d to be discovered, suggesting that steam planets and water worlds could turn out to be very common.

“Being able to work with the data at this point in my career from what’s literally the most powerful telescope that’s ever been made,” Raul concluded. “I believe it goes to show there’s never been a better time for young people to get into astronomy.”

The team’s research was published Oct. 4 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.