The need to learn how to save the world from an asteroid might seem like a no-brainer, but planetary defense missions have had a hard time gaining government support — deemed too expensive for years.

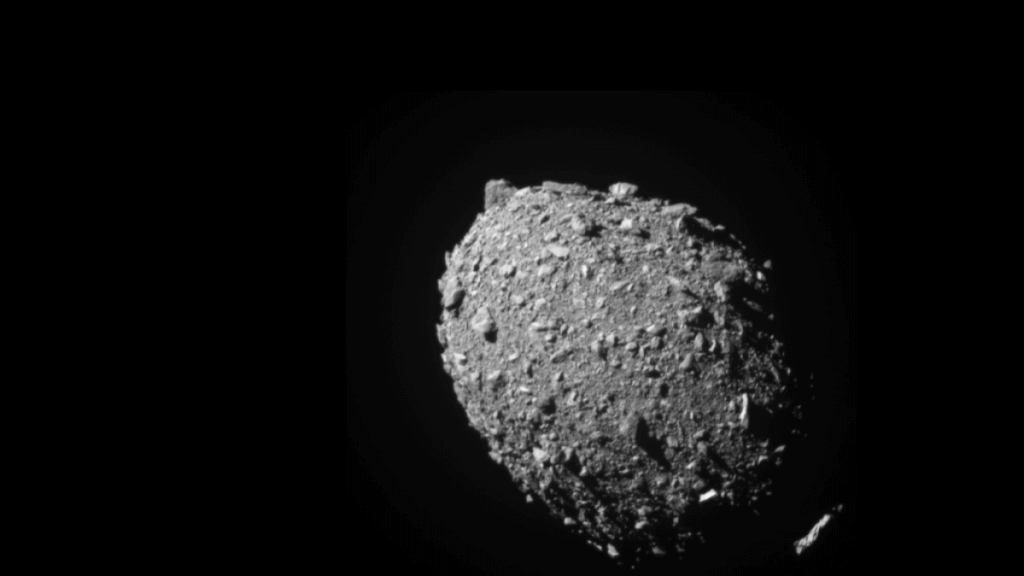

Planetary scientist Andrew Cheng, who works at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, put the D in NASA‘s DART mission, the key to making the asteroid deflection test earlier this week much cheaper. On Sept. 26, a 1,300-pound spacecraft crashed into a harmless asteroid the size of a football stadium some 6.8 million miles away to find out whether the collision could nudge the space rock.

The D stands for “double” in Double Asteroid Redirection Test, and though double of anything usually translates into more money, in this case it had the effect of greatly reducing cost. In fact, by doubling the space rocks involved, NASA essentially halved its hardware requirements.

“Did an actual light bulb appear over your head?” joked Tom Statler, a NASA program scientist, to Cheng just hours before the unprecedented spacecraft impact.

One winter morning in 2011, Cheng had an epiphany while doing his daily exercises in his basement: target a moon-like asteroid orbiting another asteroid rather than a rock flying solo through space. Nothing in particular happened to prompt this thought, like a meteorite strike on Earth or a new asteroid discovery, he admitted to a handful of reporters on Monday. It was just a random realization.

“All of a sudden, you just become aware of it: ‘Hey, I know how to do something,'” he said of the moment the idea came.

“All of a sudden, you just become aware of it: Hey, I know how to do something.”

The DART project cost the United States $325 million, with more than $300 million of that on the development of the autonomous spacecraft that was immediately destroyed on impact.

A European mission proposed in 2004 to deflect an asteroid would have needed two spacecraft launched on different trajectories — one to smash into an asteroid and another to orbit and study it for several months. The mission, dubbed Don Quijote, never got the greenlight.

Credit: Johns Hopkins APL / Craig Weiman

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

The effect of a small spacecraft on a solitary asteroid’s trip around the sun is incredibly hard to track because the change in its speed would to be on a scale of millimeters per second, Cheng explained. Detecting how the impact changed the asteroid’s orbit around a nearby rock, on the other hand, is much easier to measure. Another spacecraft wouldn’t be needed.

“We can do that with telescopes on the ground,” he said.

Scientists know that Dimorphos and its bigger asteroid companion, Didymos, make an egg-shaped loop around the sun every two years. But Dimorphos’ journey around Didymos only takes about 11 hours and 55 minutes. If the experiment worked as engineers hope, DART’s nudge should shave off about 10 minutes from that period to about 11 hours and 45 minutes, they say.

Credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins APL

Decades ago, asteroid pairs, known in astronomy as binary asteroid systems, used to be the stuff of science fiction. It took seeing such a phenomenon up close — a moonlike asteroid orbiting the Ida asteroid by NASA’s Galileo probe in 1993 — to prove their existence. Today experts estimate about 15 percent of space rocks are double or perhaps even triple asteroid systems, according to the European Space Agency.

And asteroid pairs have even slammed into Earth over the course of its long history. Researchers know this from double impact craters, likely caused by two simultaneous meteorites.

Only recently have public investments in planetary defense ramped up. Congress passed a bill requiring NASA to find and track at least 90 percent of all near-Earth objects 500 feet or larger by 2020, but lawmakers neglected to fund the program, stalling its progress for years, according to the Planetary Society, a nonpartisan space policy advocacy group. For the next five years, the survey received less than $4 million per year — “less than the travel budget for employees at NASA headquarters.”

Between 2010 and 2020, that changed with a long-term funding plan to scan the sky for space rocks and fly space missions, with funding levels increasing a whopping 40-fold. The momentum may be under threat again, however, with a proposed budget cut of over $100 million from the White House for fiscal 2023 to the NEO Surveyor, a space-based infrared telescope in development, intended to find potentially hazardous asteroids and comets.

“We’re really looking forward to having appropriate direction from the other branches of government, along with NASA leadership, to enable us to put that mission on a good schedule to launch in a few years,” Statler said.

“Of course,” he added, “we do what we’re told.”

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Planetary scientists have more work to do on the DART experiment. A follow-up European mission, Hera, will launch in late 2024 and rendezvous with Dimorphos to perform its own crash scene investigation. It will measure the asteroid’s mass and take a close look at the crater. The data should tie up the loose ends of the experiment, perhaps making DART a repeatable planetary defense technique in the future for a real threat.

So far the team is calling the DART mission a success. The exercise should instill confidence in humanity’s ability to spot potential problem space rocks and intervene long before they come anywhere close to this planet, said Elena Adams, a mission systems engineer.

“Earthlings should sleep better,” she said. “Definitely, I will.”