On Monday (Sept. 18), NASA confirmed that, after three failed attempts, its Curiosity Mars rover managed to reach a precarious destination on the Red Planet: The Gediz Vallis Ridge.

As to why this formation was worth such turmoil for Curiosity? Well, scientists believe that three billion years ago, when Mars was much wetter than the arid land it is now, powerful debris flows carried mud and boulders down the side of a mountain in the vicinity known as Mount Sharp. According to NASA, this debris “spread into a fan that was later eroded by wind into a towering ridge.”

In practical terms, that backstory means this ridge holds proof of Mars’ blue past — and maybe more excitingly, information about the planet’s ancient, dangerous landslides.

“I can’t imagine what it would have been like to witness these events,” geologist William Dietrich, a mission team member at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. “Huge rocks were ripped out of the mountain high above, rushed downhill, and spread out into a fan below. The results of this campaign will push us to better explain such events not just on Mars, but even on Earth, where they are a natural hazard.”

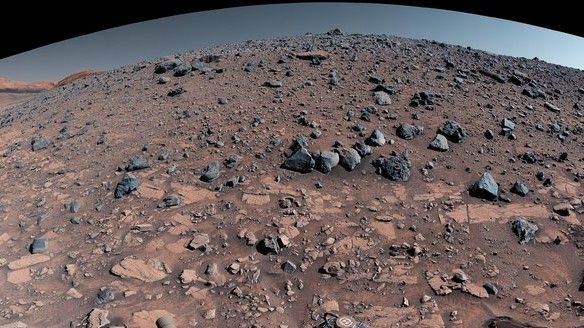

The target was reached on Aug. 14, or on the 3,923rd Martian day (sol), of the mission. After settling in, Curiosity’s Mastcam took 136 individual images of the site that were stitched together to form a 360-degree panorama that was later color-enhanced for visual purposes.

Related: How NASA’s Curiosity rover overcame its steepest Mars climb yet (video)

An inviting string of red tape

To get to the Gediz Vallis Ridge, Curiosity had to get past quite a few hurdles.

First, the rover had some trouble accessing this long-sought region on the Red Planet after scaling a spot in 2021 known as the Greenheugh Pediment, which scientists say was a tremendously difficult-to-climb rock formation.

Then, last year, Curiosity ran into some knife-edged “gator-back” rocks stippled along another possible path to the ridge. The moniker “gator-back” comes from the fact these rocks resemble scales on an alligator’s back. They’re believed to be made of sandstone — which also made them the hardest type of rock Curiosity had run into on Mars.

And earlier this year, Curiosity faced another setback on the way to Gediz Vallis after checking out the Marker Band Valley. Getting out of Marker Band, NASA said at the time, was comparable to partaking in a Martian “slip-and-slide.” That whole ordeal left Curiosity in delicate shape.

The Curiosity team called GV Ridge “the ‘Bermuda Triangle’ of Mt. Sharp,” according to a mission update from earlier this year. “We are now just a few meters away from being able to reach the arm out and get contact science on some of the ridge material, and anticipation is growing,” the update added.

But now, Curiosity has satisfied our curiosity.

“After three years, we finally found a spot where Mars allowed Curiosity to safely access the steep ridge,” Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in the statement. “It’s a thrill to be able to reach out and touch rocks that were transported from places high up on Mount Sharp that we’ll never be able to visit with Curiosity.”

To the latter point, Curiosity was never meant to make the climb towards Mount Sharp’s peak, which means dissecting rocks on the ground that once stood at the formation’s apex is a uniquely important opportunity.

The rover has been exploring the 3-mile-tall (5-kilometer-tall) mountain since 2014, stumbling upon evidence of ancient streams and such along the way, NASA explained, but Gediz Vallis ridge was a whole new area to investigate — and, in fact, the youngest section of the region.

What have we found?

According to NASA, Curiosity spent 11 days at the ridge after its mid-August arrival. During this time, it photographed dark rocks in the region that “clearly originated elsewhere on the mountain,” as well as others lower on the ridgeline, “some as large as cars.” These shards are expected to have come from higher places on Mount Sharp.

Curiosity’s Mastcam, in total, captured 136 images of the Gediz Vallis Ridge that were pieced together in a mosaic to form the 360-degree view.

Further, the team says, the rover offered scientists the first-ever up-close views of a geologic creature called a “debris flow fan,” which refers to a phenomenon where debris flowing down a slope spreads out into a fan shape.

Curiosity has been traversing its planetary subject since 2012 as part of NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory mission. So far, its journeys have taken it to incredible locations such as the Gale Crater — a large impact divot with a layered mountain at its center — and (more adorably) this rock that looks like an open book.

With Gediz Vallis under its belt at last, Curiosity is headed to find a path above the ridge to learn about the watery history of Mount Sharp.