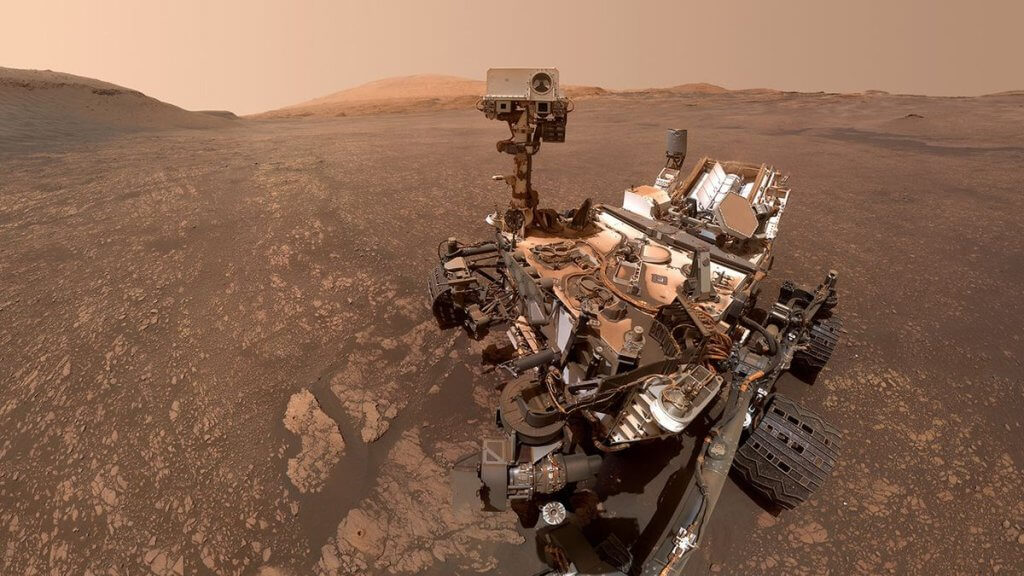

NASA’s Curiosity rover is doing well after fighting dust, wind and age for 4,000 Red Planet days.

Curiosity recently passed 4,000 “sols,” or Red Planet days, on Mars since landing on Aug. 5, 2012. (One sol is slightly longer than an Earth day — about 24 hours and 40 minutes.) The rover is a key part of NASA‘s search for life on Mars and continues to pull up evidence of minerals, rocks and other parts of the environment shaped by water.

A newly drilled sample may, scientists say, add to its flood of evidence. Nicknamed “Sequoia,” the clump collected from the flank of the 3-mile-high (5 kilometers) Mount Sharp could show evidence of sulfates. Those are minerals formed in salty water evaporating from Mars as it began to lose water billions of years ago, presumably as its atmosphere thinned, scientists say.

Related: Curiosity rover discovers new evidence Mars once had ‘right conditions’ for life

Curiosity has already found abundant sulfates, and it continues to seek elusive carbonate reserves that appear to be rare on the Red Planet. (Carbonate suggests an atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide, so if Mars used to have a thick atmosphere of this type, it’s unclear why that carbonate is so hard to find.)

“We’ve been anticipating these results for decades, and now Sequoia will tell us even more,” Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory near Los Angeles, said in an agency statement on Monday (Nov. 6).

Water was very much on Vasavada’s mind during my first interview with him as a Space.com reporter, for a piece that was published on July 27, 2012, just a week or so before Curiosity’s Aug. 5 touchdown. We were talking about the Russian-made Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) experiment designed to shower the surface with 10 million neutrons per pulse. (Curiosity’s blog hasn’t mentioned DAN since December 2021, before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that severed most space partnerships with Russia.)

“The goal is, in about 20 minutes of pulsing and returning and detecting the signal, [the rover] can build up a fairly good understanding of how much water there is below the surface,” Vasavada, then Curiosity’s deputy project scientist, told me of DAN in a phone interview.

I remember how surreal that conversation was for me. I had met Space.com representatives at the overnight launch of the space shuttle mission STS-130 two years before, on Feb. 8, 2010, having journeyed to Florida from Canada prospecting for business as a young reporter. (My part-time workplace’s building in Ottawa, Canada, also burned down the night before, which is a whole other story.)

Anyway, 30 months later, a phone call from now editor-in-chief Tariq Malik (who somehow preserved my business card in the interim) invited me to write my first Space.com story in July 2012, on this complicated Mars instrument. Before long, a flow of Curiosity-related story requests began to appear in my inbox, allowing me to rocket away from business reporting — my specialty at the time — and flow freelance-style into my passion of space.

Related: Water on Mars may have flowed for a billion years longer than thought

Space.com remained my anchor client for an incredible decade before kindly offering me a full-time job on July 20, 2022 (yes, the anniversary of the pioneering Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, and Viking 1’s first-ever Mars landing in 1976). So, as Curiosity continues its journey on Mars, I feel a special connection to the mission.

I even had the privilege of visiting Curiosity’s powerful sibling rover mission, Perseverance, at JPL during a tour for book-writing in September 2019. Both of these missions form a long line of missions on Mars searching for signs of water and by extension, the origins of life on Earth and other planets. Perseverance, in fact, is actively searching for signs of ancient Mars life; Curiosity, by contrast, is looking for evidence of past habitable environments.

Decades of work at the Red Planet, mostly since the 1990s, have revealed vast evidence of water, from both satellite missions and excursions to the surface. Polar caps have the substance locked up in the ice. Preserves of some kind may lurk beneath the surface, although how much Martian underground water exists is considerably debated. And, in my favorite example, the small NASA Spirit and Opportunity Mars Exploration Rovers (fondly remembered) came across evidence of features nicknamed “blueberries.” These are hematite-rich concretions formed in water whose exact origins remain unclear decades after they were first found.

Curiosity’s work has been valuable as well, including stumbling on an ancient riverbed weeks after its landing, and finding signs of past water activity high up on Mount Sharp as it ascends and carefully documents the rocks. Among numerous other finds that have helped extend its science mission four times, Curiosity recently uncovered widespread evidence of rivers at its Gale Crater landing site.

Also, Curiosity’s team just published results of a magnesium sulfate mineral called starkeyite, a dry-climate mineral spotted with the rover’s Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument. The peer-reviewed work was published Oct. 30 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets and was led by the Planetary Science Institute’s S. J. Chipera.

While the dry find sounds paradoxical for water, NASA emphasizes that starkeyite is important.

“The team believes that after sulfate minerals first formed in salty water that was evaporating billions of years ago, these minerals transformed into starkeyite as the climate continued drying to its present state,” agency officials wrote in the same statement on Monday. “Findings like this refine scientists’ understanding of how the Mars of today came to be.”

Related: Landslides on Mars suggest water once surrounded Olympus Mons, tallest volcano in the solar system

Curiosity is still healthy after putting in a total of 20 miles (32 kilometers) on the road, which is bringing it close to the 28 miles (45 km) that Opportunity racked up during its 14 years of work. As of this writing, engineers are working to address a minor issue with a camera on Mastcam, considered one of the main “eyes” of Curiosity that provide sharp color views. A filter under the lens has been frozen between positions, but NASA engineers are trying to slot it back in place.

“If unable to nudge it back all the way, the mission would rely on the higher-resolution 100 mm focal length right Mastcam as the primary color-imaging system,” NASA officials stated. “As a result, how the team scouts for science targets and rover routes would be affected: The right camera needs to take nine times more images than the left to cover the same area. The teams also would have a degraded ability to observe the detailed color spectra of rocks from afar.”

In the longer term, Curiosity’s nuclear power source, which harnesses the energy given off by the radioactive decay of plutonium, continues to dwindle, but mission team members stress that the rover still has years of life in it. Repeated use, dust and wind are also slowly wearing down Curiosity’s rock-boring drill and the joints in its robotic arm, but, on the other hand, software updates are making the drives of Curiosity more efficient. Engineers have even slowed down the worrisome wear on the rover’s treaded wheels.

Curiosity is working on its own for the next few weeks. Until Nov. 28, NASA will freeze communications with the rover during solar conjunction, when Mars flies behind the sun from the perspective of Earth. Since plasma from the sun can interfere with communications, the agency always stops sending commands to its Mars robots at this time. But Curiosity is still working on a “to-do list” for these next few weeks, until agency officials can talk with the long-running rover again.

Perseverance is also doing well after its Feb. 18, 2021 landing inside Jezero Crater. The rover is caching samples of an ancient lakebed for future return to Earth (though that planned return mission is working through budget issues at the moment) that may reveal ancient signs of microbial life in the rock. Meanwhile, a companion helicopter called Ingenuity is well past 60 flights on Mars, showing that aerial vehicles can act as a scout and helper for other missions that may follow.