Humanity dodged an orbital bullet recently by an even slimmer margin than we thought.

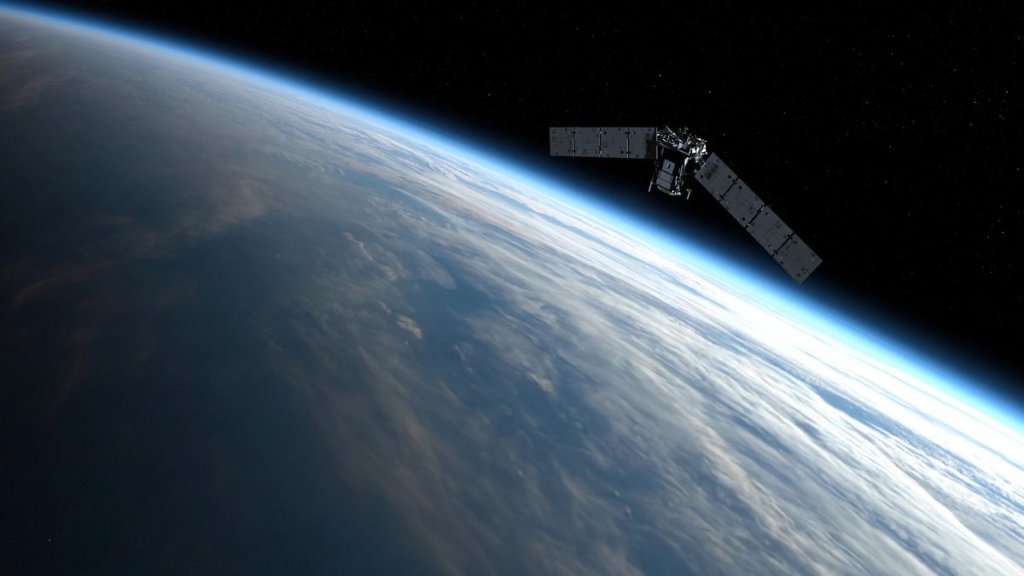

In the wee hours of Feb. 28, the dead Russian spy satellite Cosmos 2221 and NASA’s TIMED craft, which has been studying Earth’s atmosphere since 2001, made an uncomfortably close pass in orbit, zooming within a mere 65 feet (20 meters) of each other.

That was the initial estimate, anyway. Further study has shown that the shave was actually even closer, according to NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy.

“We recently learned through analysis that the pass ended up being less than 10 meters [33 feet] apart — within the hard-body parameters of both satellites,” Melroy said April 9 during a presentation at the 39th Space Symposium in Colorado Springs.

“It was very shocking personally, and also for all of us at NASA,” she said, adding that the encounter “really scared us all.”

Related: 7 wild ideas to clean up space junk

She explained the concern: “Had the two satellites collided, we would have seen significant debris generation — tiny shards traveling tens of thousands of miles an hour, waiting to puncture a hole in another spacecraft, potentially putting human lives at risk.”

This is not merely a theoretical issue. In August 2021, for example, the Chinese military satellite Yunhai 1-02 got whacked by a piece of space junk — apparently a bit of debris from the Zenit-2 rocket that launched Russia’s Tselina-2 spy satellite in 1996.

While such hits remain rare, near misses such as the one TIMED survived are becoming more and more common, for Earth orbit is getting more and more crowded.

There are currently about 11,500 satellites circling our planet at the moment, 9,000 of which are operational, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). More than half of these functional craft, by the way, are part of SpaceX’s Starlink broadband network; the ever-growing megaconstellation currently consists of nearly 5,800 satellites.

But that’s just part of the picture. There are about 36,500 pieces of space junk at least 4 inches (10 centimeters) wide in Earth orbit, ESA estimates, and more than 130 million shards at least 1 millimeter across.

As Melroy noted, even such tiny slivers of debris can do damage to satellites and the International Space Station (ISS), given the velocities involved. At the ISS’ orbit, about 250 miles (400 kilometers) up, objects move at around 17,500 mph (28,160 kph) — far faster than any bullet.

NASA has worked over the years to help mitigate the space-junk problem, Melroy added. As an example, she cited the agency’s work two decades ago to help implement “common-sense practices,” such as the passivation of rocket upper stages in orbit — a process that involves, among other actions, venting their remaining fuel to reduce their explosive potential.

But the agency wants to do more, Melroy said. And that increased push includes an integrated “space sustainability strategy,” the first part of which NASA released the day of Melroy’s talk.

“Developed under the leadership of a crossagency advisory board, the space sustainability strategy focuses on advancements NASA can make toward measuring and assessing space sustainability in Earth orbit, identifying cost-effective ways to meet sustainability targets, incentivizing the adoption of sustainable practices through technology and policy development, and increasing efforts to share and receive information with the rest of the global space community,” agency officials said in an April 9 statement.

NASA’s sustainability strategy will eventually encompass four domains: Earth, Earth orbit, cislunar space (the region near and around the moon) and deep space. The 35-page first volume focuses on sustainability in Earth orbit, agency officials said.

You can learn more about the sustainability strategy, and read the first volume, via NASA here.