Astronomers are once again ringing alarm bells about rising light pollution destroying pristine night skies. This time, though, their worries extend beyond their core discipline.

“We astronomers are sort of the canary in the coal mine,” James Lowenthal, a professor of astronomy at Smith College in Massachusetts, said last week at the American Astronomical Society (AAS) conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “Practically every species that’s studied is affected negatively [by light pollution].”

With eyes on the sky, astronomers have long voiced concerns about increasing yet mostly unregulated artificial urban lighting and satellite megaconstellations such as SpaceX’s Starlink impacting valuable observations of deep-space objects by ground-based observatories, which are considered the real workhorses of space science and are more severely impacted by light pollution than their space-based counterparts.

Now, a study published on Thursday (June 15) provides a comprehensive summary of the harmful effects of light pollution and paints a rather grim picture of the future for professional and amateur astronomers.

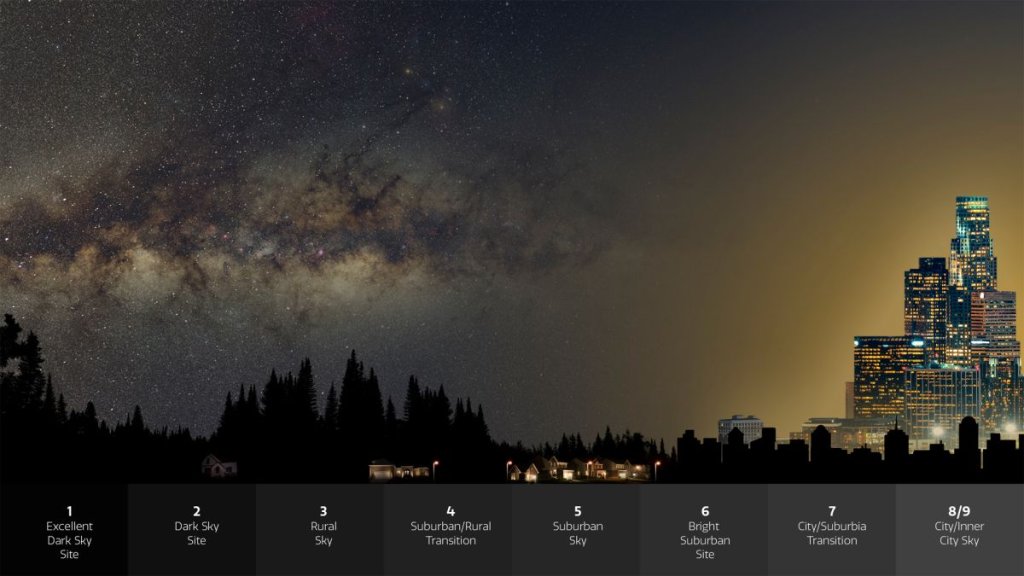

It says that more than 80% of the world’s population currently lives under light-polluted skies that are getting contaminated at a breakneck pace of nearly 10% each year, which is much higher than previously thought. Meanwhile, the sales of LEDs (light-emitting diodes) — which emit large amounts of blue light that scatters widely in Earth’s atmosphere and deteriorates the quality of telescope observations — have increased by 18% in the last five years and are expected to spike by a further 15% by 2027, reaching a revenue of $141 million per year, according to study author Antonia Perez, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC) in Tenerife, Spain.

The study echoes astronomers’ worry that they are running out of places on Earth to set up observatories, as even the most remote locations are witnessing a decline in the darkness of night skies. About 5 to 10% of artificial satellites, which photobomb telescope observations and glisten under sunlight for long durations, are gliding above telescope sites at any given time, Perez wrote in the new study.

“It really paints a picture of astronomy as under assault from virtually all sides,” John Barentine, a principal consultant at Arizona-based Dark Sky Consulting and the former director of public policy at the International Dark Sky Association, told Space.com. “I’m particularly struck by the dire threat this all poses to non-professional users of the night sky, including amateur astronomers, astrophotographers and astro tourists. Here, too, the matter is not merely one of the loss of the intangible, but also one of dollars and cents.”

The new study also states that NASA’s Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a ground-based telescope currently being constructed in Chile to unlock a new era of investigating the cosmos by watching a wider view of the universe than its predecessors, likely will need to discard 40% of its images due to satellite trails. Additionally, half of the night sky images clicked close to dawn or dusk — when many low-orbiting satellites become visible to the naked eye and glint with reflected sunlight for long periods before and after twilight — are said to be contaminated with bright streaks from satellite trails.

And it’s only going to get worse. In the coming years, about 400,000 satellites are predicted to crowd low-Earth orbit.

“The astronomical community did not become aware of the issue until spacecraft were already being launched,” Perez wrote in the new study.

The Committee for the Protection of Astronomy and the Space Environment (COMPASSE) is an AAS wing tasked with raising awareness about light pollution among various sectors, including federal agencies and policymakers. Lowenthal, who is the committee’s vice chair for light pollution, said the group grew largely due to increasing concerns about the hundreds of satellites launched into low Earth orbit by SpaceX and OneWeb, each of which can mar telescope observations by reflecting sunlight. For example, SpaceX has already launched nearly 4,600 satellites just for its Starlink constellation alone.

“That’s what really gave us the shot in the arm,” Lowenthal said during the news briefing last week. “We’d sort of just been limping along for year after year with the same old kind of light pollution, and then that crisis happened, and it lit a fire under us.”

Related: Losing darkness: Satellite data shows global light pollution on the rise

Not just an astronomy problem

Astronomers have recently realized that light pollution is not just an astronomy problem, and that working with other groups that are more concerned about other things than the night sky — like those in the lighting industry, ecological and environment conservation groups as well as public policy practitioners, could be a more effective way to regulate light pollution, Lowenthal said.

“I think we are at a turning point, not only because of this dramatic rise in light pollution,” he said, “but also because of our growing realization as dark sky advocates that this problem should not be limited to astronomy.”

Yet putting a cap on light pollution in cities is challenging. By and large, the standards for lighting are not backed by science, so it is not surprising that most cities and towns worldwide are over-illuminated — brighter than they need to be, while also burning excessive energy — the new report states, adding that outdoor lighting in cities absorbs half of a city’s energy bill.

“We’ve known for decades how to reduce light pollution technically. The big question is, How do we get the individuals who choose and install lighting to make good choices?” Christopher Kyba, a light pollution researcher at the Ruhr University Bochum in Germany, told Space.com.

Kyba led a recent study that quantified the likely coming effects of light pollution. Locations where 250 stars are currently visible with the naked eye in the night sky will see that stellar bounty shrink to 100 in less than two decades, Kyba’s team found.

A rare beacon of light (so to speak) is Arizona’s Coconino County, which in 1958 enforced the world’s first lighting ordinance to limit use of non-emergency searchlights and later enacted another piece of legislation to restrict the amount of lighting per acre of Flagstaff, the world’s first international dark sky location and home to the well-known Lowell Observatory.

Related: 21 amazing dark sky reserves around the world

For decades, cities in the Coconino County worked with regulators to set and enforce ordinances. They succeeded in showing that “it can be done to have the lights that you might feel you need in your city for safety and security without ruining the environment, human health and the night sky,” Lowenthal said, calling the county a “true model for how to do it right.”

Darker skies are beneficial to not just astronomers, but also to countless nocturnal animals that depend on moonlight and starlight to navigate their surroundings in search of food, shelter and partners. Artificial skyglow has been shown to disrupt the lunar compasses deeply ingrained in those species, often one of their key tools for fitness and survival.

Humans too, are impacted. Previous research has found that light pollution messes with the light-driven circadian clock and prolongs the time it takes for us to fall asleep. And other studies have linked light pollution to a higher risk of obesity and depression.

“Our choices today will set consequences and precedents for centuries to come,” Aparna Venkatesan, a cosmologist at the University of San Francisco who advocates for space to be viewed as a globally shared environment and heritage, told Space.com. “We are accountable not only to future scientists, but also future storytellers, artists, songwriters and practitioners of cultural sky traditions.”

The new research is described in a paper published Thursday (June 15) in the journal Science.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @skuthunur. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.