Even the toughest microbe couldn’t survive for long on Mars‘ tortured desert ground.

Deadly radiation from the cosmos pummels the surface. The temperature averages minus 80 degrees Fahrenheit. In the profoundly dry, sparse atmosphere, a cup of water would immediately vaporize.

Yet beneath the hellish ground, hardy microbes — if they ever existed — could have endured for millions of years. And by eluding the threats from above, this life may even have survived until today. “There’s no escape unless you’re deeply buried under the surface,” Michael Daly, a professor of pathology at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, a university run by the federal government, told Mashable.

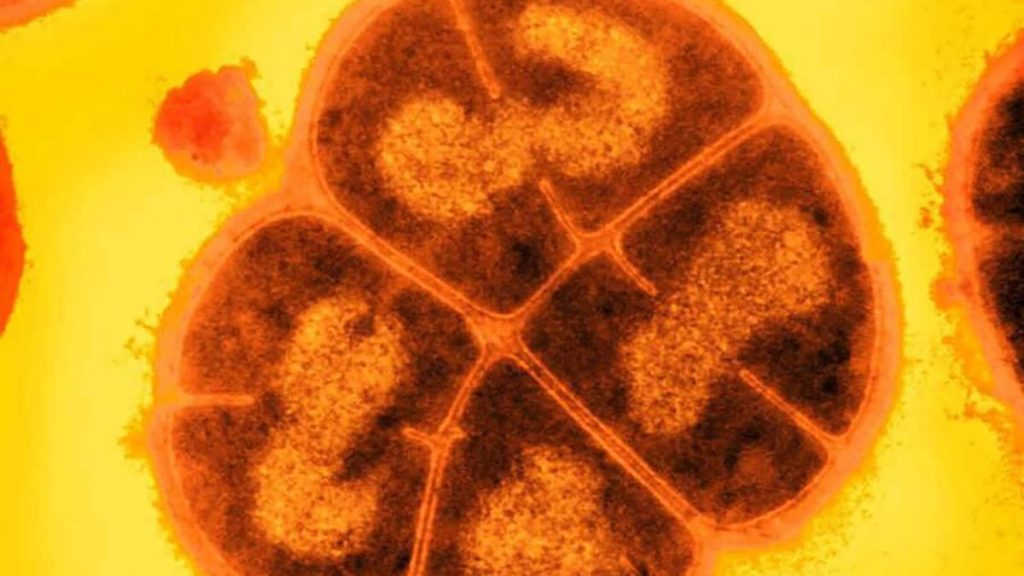

Daly and a team of scientists recently published new research in the space journal Astrobiology showing that an incredibly robust earthly microbe, Deinococcus radiodurans — which survives in nuclear reactors — could endure for millions of years if buried underground. The farther down, the more protection. By exposing the bacteria to intensive radiation in a laboratory, the scientists concluded D. radiodurans could weather radiation for 1.5 million years at some four inches down. But at around 30 feet, the buried microbe could endure, in a dormant state, for 280 million years. “That’s a shocking amount of time,” Daly noted.

You read that right: 280 million years. To prove the tiny organism could withstand such hostile radiation environs, they showed it no mercy. “The cells were exposed to truly astronomical doses of radiation,” Daly emphasized. He noted that when dried and frozen in simulated subsurface Mars-like conditions, D. radiodurans tolerated 140,000 grays of radiation (a “gray” is a unit of radiation that something, or somebody, absorbs). That’s 28,000 times the amount of radiation that would kill a person.

Indeed, the barren Martian surface looks lifeless today. But if an extremely radiation-resistant microbe like D. radiodurans could evolve on Earth, something similar could potentially do the same on Mars, a planet once habitable, and flush with water.

“It’s so important for us to recognize that life is so tenacious.”

What’s more, microbial life on Earth thrives in uninviting underground realms. “We know life on Earth lives kilometers down in bedrock,” Amy Williams, an astrobiologist at the University of Florida who was not involved in the new research, told Mashable.

“It’s so important for us to recognize that life is so tenacious,” Williams, who works on NASA’s Mars Perseverance and Curiosity rover missions, added. “We could be meters away from discovering our closest planetary neighbors.”

Credit: Michael Daly / USU

How Martian life might survive

For good reason, the microbe D. radiodurans is dubbed “Conan the Bacterium.”

When exposed to a powerful, damaging type of radiation that can change and damage tissue — called “ionizing radiation” — this microbe can (amazingly) repair broken apart genetic material. These bacteria also produce chemicals that protect them from radiation. And you needn’t look far to find them. They’re everywhere. They’re in the soil. “They’re found in our stomach and gastrointestinal tract,” noted Daly.

Researchers already knew D. radiodurans could likely survive for some 1.2 million years just below the Martian ground. But no one had ever tested D. radiodurans in truly underground Martian-like conditions, where the hardy organism would be buried in a freezing and immensely dry place. Until now. The researchers completely dried out the microbes in “desiccation chambers.” Then they zapped the frozen and dry D. radiodurans with intense radiation for days.

“We have shattered all previous records of ionizing radiation resistance,” Daly said.

“There’s no escape unless you’re deeply buried in the surface.”

So while a microbe like D. radiodurans might only last a few hours on the irradiated Martian surface, underground it may last for ages, until the radiation eventually takes its toll.

“It’s compelling in that it gives us context for how life could have survived on Mars, if it ever arose,” said Williams.

Enduring for hundreds of millions of years, however, means surviving as a frozen spore or microbe. And perhaps, at times, the microbes could reanimate when conditions changed or a thaw occurs. On Earth, for example, NASA scientists successfully thawed ice age bacteria that had been frozen for some 32,000 years. The frozen life revived.

How might a Martian bacteria thaw and reanimate? Mars is constantly pelted with big space rocks. They don’t burn up in the thin Martian surface, so they pummel the ground and make new craters. There are countless places where the bombarded surface has heated from tremendous impacts. Ice, which is plentiful in parts of Mars’ subsurface, could melt, too. This all creates an inviting environment, though temporary, for microbes to once again repopulate and spread, Daly said. The organisms would likely freeze again, and lurk in dormancy.

Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

Credit: NASA

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

A future robotic mission could probe the Martian subsurface for this potential, frozen life. The European Space Agency’s much-anticipated Rosalind Franklin rover — which may not launch until 2028 — will drill a couple meters below the surface in search for hints of Martian life, whether past, or possibly even present. “The ESA-led Rosalind Franklin rover has a unique potential to search for evidence of past life on Mars thanks to its drill and laboratory,” the ESA writes. “It will be the first rover to drill 2 m below the surface, and the first to use novel driving techniques, including wheel-walking, to overcome obstacles.”

Such a mission is a major, if not thrilling, leap in the effort to seek otherworldly life. “You’re potentially looking for an ecosystem that still exists,” noted Williams. “If you pulled up some of these cells, you could potentially detect them.”

(Crucially, some missions to Mars, like NASA’s Mars Sample Return Program, will blast rocky Martian samples back to Earth. This new research underscores that we should be wary: If not careful, we could contaminate Earth with hardy Martian microbes.)

Still today, there remains zero evidence that living organisms exist anywhere beyond Earth — though there are certainly enticing worlds in our very solar system that could harbor life. We’re scouring the Martian surface for even hints of life, though it’s unknown if we’ll ever find compelling evidence. But microbes on Earth thrive in extreme places. In lightless places. In torrid hot springs. In acid. In toxic waste. Why not under the Martian ground?

“Microbes are incredibly resilient,” said Williams. “They will find a way, if it’s possible.”

This story was originally published on Oct. 30, 2022.