WASHINGTON — Kall Morris Inc. announced Sept. 7 it received three study contracts for debris-cleanup technologies under the Space Force’s Orbital Prime program.

KMI, based in Michigan, is a research and development startup focused on space debris remediation.

Orbital Prime is run by SpaceWERX, the technology arm of the U.S. Space Force. In May it selected 125 industry teams for the initial phase of the program, intended to promote commercial development of technologies for orbital debris cleanup and other space services.

KMI’s three awards, worth $750,000, are Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) contracts which require small businesses to team with academic or nonprofit institutions. The winners of the first phase of Orbital Prime can compete for larger follow-on contracts.

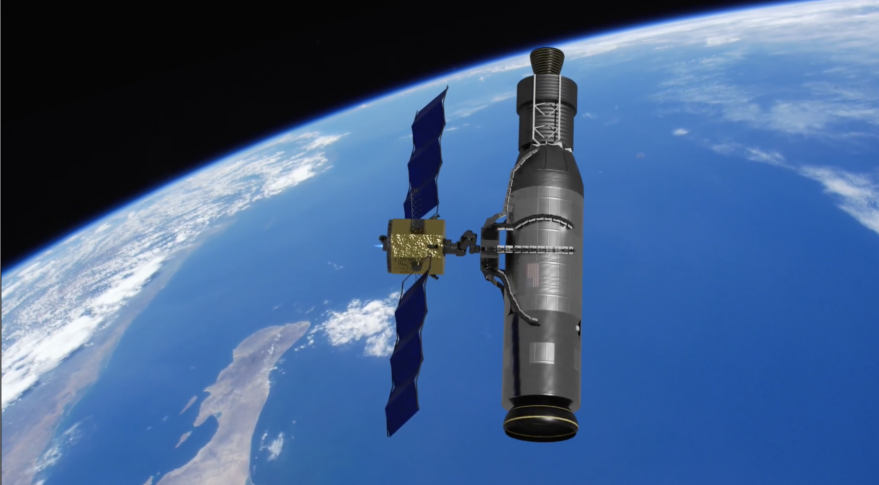

The company is pitching a debris removal concept that uses adhesive arms — a technique known as gecko adhesion — to capture debris objects like inert satellites and rocket bodies that are flying in orbit uncontrolled and are unprepared for capture.

For each of the three Orbital Prime awards, KMI partnered with different universities. It’s working with the University of Southern California’s Space Engineering Research Center to refine the adhesive arms concept. It teamed with Stanford University’s Biomimetics and Dexterous Manipulation Lab to explore other adhesion techniques, and with MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics to examine ways to conduct debris collection and analysis.

Troy Morris, KMI co-founder and director of operations, said the teaming between the private sector and universities enhances the quality of the proposals. “Universities provide technical support, a great wealth of experience and testing resources,” he said. “It helps small businesses so we don’t have to go out and rebuild or buy something that’s already sitting in their lab.”

Business case for debris removal

Morris said companies participating in the Orbital Prime program hope it will lead to an actual debris-removal mission and a commitment from the U.S. government to buy cleanup services from the private sector.

A major hurdle for the industry, he said, is that there are no credible estimates of what it will cost to remove tens of thousands of debris objects that are making space operations increasingly dangerous due to the risk of collisions.

Removing space junk is a huge technical challenge and some companies already are demonstrating it’s possible. The hardest piece is the business case, said Morris. “It’s having the proper signaling from the Space Force, commercial operators and others to prove to investors that there’s a real market that can go forward and fix the problem.”

Morris said the most concerning debris are large rocket bodies that would obliterate spacecraft in a collision. Most are upper stages of rockets launched decades ago that were never designed to be captured or dock with other vehicles.

Companies in the space industry have adopted sustainability plans to minimize debris such as deorbiting non-functioning satellites, but the number of debris objects is still on the rise, Morris said.

Many in the space industry believe there’s a future market not just in retrieving and removing junk but also repurposing, said Morris, as rocket bodies would provide raw materials to manufacture hardware in orbit.