Japan sent two ambitious missions soaring into the heavens today (Sept. 6) — a pioneering lunar lander and a powerful X-ray space telescope.

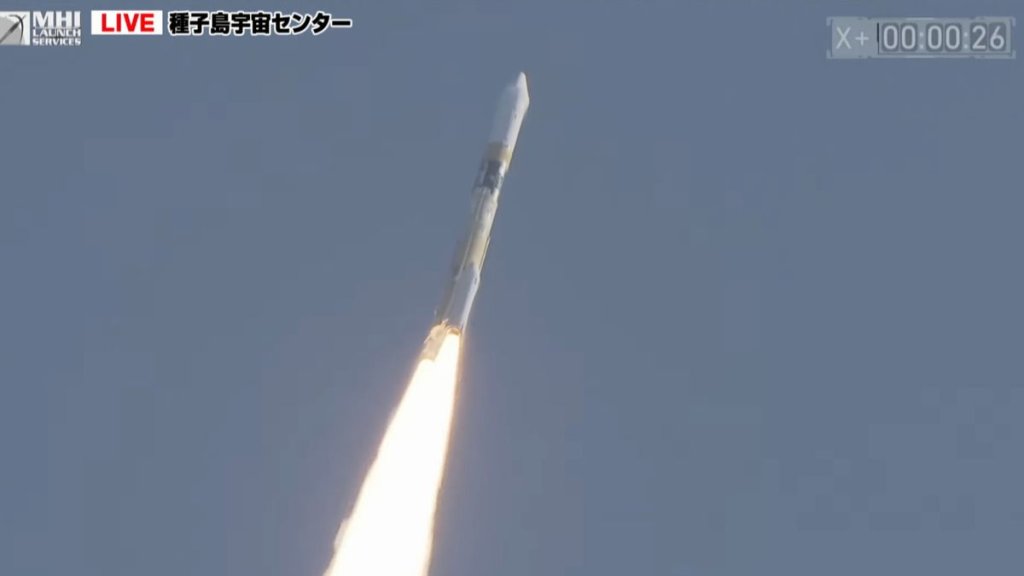

A Japanese H-2A rocket carrying the SLIM moon lander and the XRISM space telescope lifted off from Tanegashima Space Center today (Sept. 6) at 7:42 p.m. EDT (2342 GMT; 8:42 a.m. Japan time on Sept. 7). That was about 10 days later than originally planned, thanks to weather delays.

Both spacecraft were deployed on schedule, sequentially less than an hour after liftoff. If all goes according to plan, a few months from now, SLIM (“Smart Lander for Investigating Moon”) will attempt to pull off Japan’s first-ever soft lunar landing — a pinpoint touchdown that will pave the way for even more ambitious feats down the road.

SLIM “aims to achieve a lightweight probe system on a small scale and use the pinpoint landing technology necessary for future lunar probes,” officials with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) wrote in a mission description.

“The project will aim to cut weight for higher-function observational equipment and to land on resource-scarce planets, with an eye towards future solar system research probes,” they added.

Related: Missions to the moon: Past, present and future

Shooting for the moon

SLIM is a small spacecraft, measuring just 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) high, 8.8 feet (2.7 m) long and 5.6 feet (1.7 m) wide. At liftoff, it tipped the scales at about 1,540 pounds (700 kilograms), but roughly 70% of that weight was propellant.

SLIM will take a long, looping and fuel-efficient route to the moon, finally reaching lunar orbit three to four months from now. It will then eye the lunar surface for another month or so before attempting a touchdown inside Shioli Crater, a 1,000-foot-wide (300 m) impact feature that lies at 13 degrees south latitude, on the moon’s near side.

The probe aims to land within 330 feet (100 m) of a target point within Shioli Crater — a more precise touchdown than previous lunar landers have attempted. The goal is to demonstrate pinpoint-landing tech that could open the moon, and other celestial bodies, to more extensive exploration.

“By creating the SLIM lander, humans will make a qualitative shift towards being able to land where we want and not just where it is easy to land, as had been the case before,” JAXA officials wrote in the mission description. “By achieving this, it will become possible to land on planets even more resource-scarce than the moon.”

SLIM also carries two miniprobes, which will be ejected onto the lunar surface following touchdown. Those two little craft will help the mission team monitor the status of the larger lander, take photos of the landing site and provide an “Independent communication system for direct communication with Earth,” according to JAXA’s mission press kit.

SLIM isn’t the first lunar lander that JAXA has built. The agency’s tiny OMOTENASHI craft was one of 10 cubesats that launched with NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission in November 2022. While Artemis 1 succeeded, OMOTENASHI did not; its handlers could not establish communications with the little probe in time for its planned touchdown try. (Several of the other Artemis 1 cubesats failed in their missions as well.)

And a Japanese lander has tried its hand at a lunar touchdown before. The Tokyo-based company ispace’s Hakuto-R lander reached lunar orbit — a huge accomplishment for a private spacecraft — but crashed during its touchdown attempt this past April.

Success by SLIM would therefore be historic. Just four nations have soft-landed a probe on the moon to date — the Soviet Union, the United States, China and India. India put its name on this exclusive list just last month, when its Chandrayaan-3 mission touched down near the lunar south pole.

Related: See 1st photos of the moon’s south pole by India’s Chandrayaan-3 lunar lander

An X-ray space telescope, too

As exciting as SLIM is, it’s merely the secondary payload on Sunday’s launch. The main spacecraft is XRISM, which is headed for a perch in low Earth orbit.

XRISM (short for “X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission”) is a collaboration involving JAXA, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). As its full name suggests, the telescope will study the universe in high-energy X-ray light.

“X-ray astronomy enables us to study the most energetic phenomena in the universe,” Matteo Guainazzi, ESA project scientist for XRISM, said in a statement.

“It holds the key to answering important questions in modern astrophysics: how the largest structures in the universe evolve, how the matter we are ultimately composed of was distributed through the cosmos, and how galaxies are shaped by massive black holes at their centers,” he added.

The observatory will focus particularly on the super-hot gas surrounding galaxy clusters.

“JAXA has designed XRISM to detect X-ray light from this gas to help astronomers measure the total mass of these systems,” ESA officials wrote in the same statement. “This will reveal information about the formation and evolution of the universe.”

XRISM won’t be the only X-ray telescope studying the heavens from Earth orbit. Also up there right now, for example, are NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton, both of which launched in 1999, as well as NASA’s NuSTAR, which lifted off in 2012.