NASA’s massive new space telescope just keeps getting colder.

While the James Webb Space Telescope‘s slow cooling process is nearing its end, NASA officials wrote in an update, there’s no firm timeline on when all the observatory components will meet their operating temperatures. That’s because much of this stage of the telescope’s months-long commissioning period comes down to physics, as mission managers wait for the mirrors to naturally cool to a temperature to allow alignment to continue.

All of the observatory’s instruments are at their final temperature, including the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), which is super-sensitive to heat and gets some help from a cryocooler to stay around 7 degrees Kelvin (minus 447 degrees Fahrenheit or minus 226 degrees Celsius). Webb needs to retain such ultracool temperatures to detect infrared light in heat-emitting wavelengths.

The mirrors, however, “are not quite there yet,” Jonathan Gardner, Webb deputy senior project scientist, said in the update, which was posted on Thursday (April 21).

Live updates: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope mission

Related: How the James Webb Space Telescope works in pictures

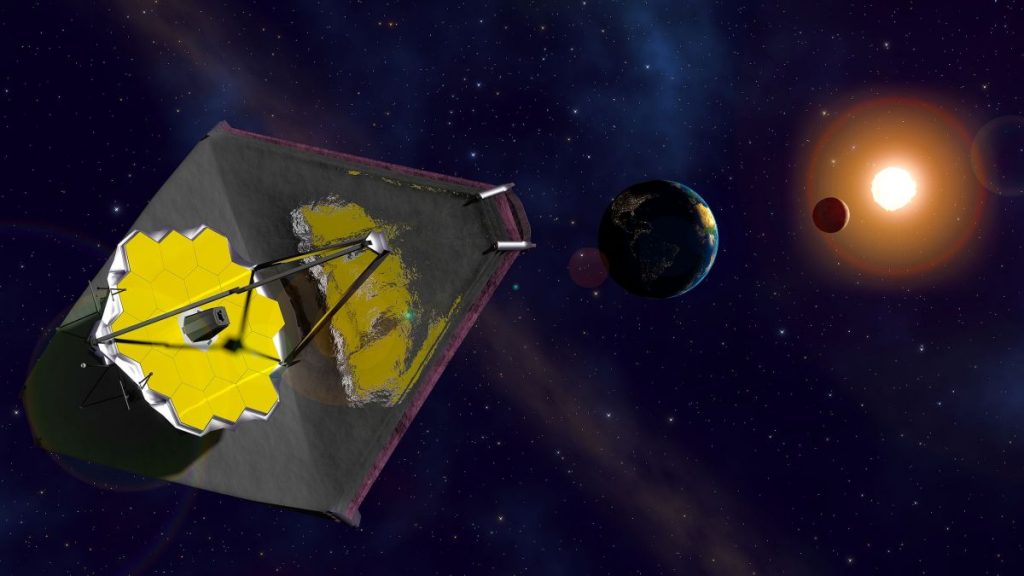

That’s because the 18 hexagonal segments of the primary mirror, as well as the secondary mirror, are all made of beryllium and coated with gold. “At cryogenic temperatures, beryllium has a long thermal time constant, which means that it takes a long time to cool or to heat up,” Gardner explained.

The $10 billion telescope has been cooling ever since its launch on Dec. 25, 2021, and it’s making good progress so far, Gardner said. All of the primary mirror segments are below the mark of 55 Kelvin (minus 360 F or minus 218 C) necessary for MIRI to operate. Further cooling “will only enhance its performance,” Gardner said.

Of the 18 primary mirror segments, just four of them are above the 50 Kelvin (minus 370 F or minus 223 C) mark. Since these segments all have some mid-infrared light that reaches MIRI detectors, the agency stated, officials would prefer to see them cool by an additional 0.5 to 2 Kelvins each before starting the next phase of alignment.

These temperatures are all subject to fluctuation, Gardner noted. The telescope and sunshield operate together when the telescope is aimed at something. There is a “tiny amount of residual heat,” he says, that can move through the five-layer sunshield to the primary mirror depending on the angle the sunshield presents to the sun, or the attitude.

“Since the mirror segment temperatures change very slowly, their temperatures depend on the attitude averaged over multiple days,” he said. In fact, Webb has been spending most of the commissioning period pointing at the poles of the ecliptic, or the plane upon which solar system planets orbit the sun.

This polar attitude, Gardner said, “is a comparatively hot attitude.” But that’s temporary, he added. “During science operations, starting this summer, the telescope will have a much more even distribution of pointings over the sky. The average thermal input to the warmest mirror segments is expected to go down a bit, and the mirrors will cool a bit more.”

A little later in commissioning, Gardner added, the team plans to test Webb’s ability to transition from a “hot attitude” to a “cold attitude.” This thermal slew process “will inform us how long it takes for the mirrors to cool down or heat up when the observatory is at these positions for any given amount of time.”

Webb still should be finished its commissioning in about June, Gardner said. “Is Webb at its final temperature? The answer is almost,” he concluded.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.