Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have gained a more detailed picture of the turbulent “pancakes” of gas and dust surrounding young stars, feeding them and facilitating their growth before birthing planets.

JWST gathered new details about the “winds of change” flows of gas that blow through these protoplanetary disks, carving out their shapes. In the process of doing this, the powerful space telescope saw evidence for a long-hypothesized mechanism that allows a young star to gather the material from the disk that it needs to grow.

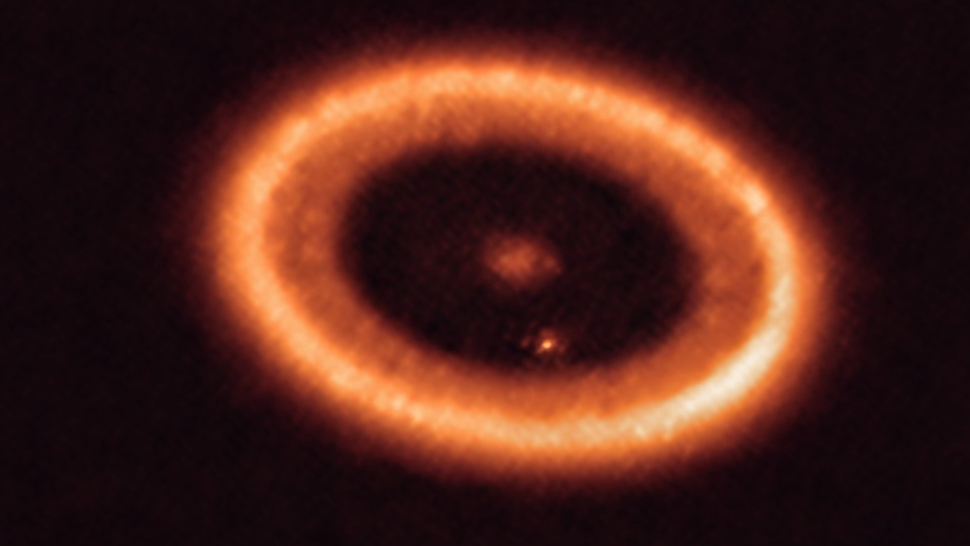

A team led by astronomers from the University of Arizona gathered observations of four protoplanetary disk systems, all of which appear edge-on when viewed from Earth. Constituting the most comprehensive look at the forces that shape protoplanetary disks, they offer a snapshot of what our solar system and infant sun looked like around 4.6 billion years ago, before the formation of Earth and the other planets.

“Our observations strongly suggest that we have obtained the first detailed images of the winds that can remove angular momentum and solve the longstanding problem of how stars and planetary systems form,” team leader Ilaria Pascucci, of the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, said in a statement.

“How a star accretes mass has a big influence on how the surrounding disk evolves over time, including the way planets form later on,” Pascucci said. “The specific ways in which this happens have not been understood, but we think that winds driven by magnetic fields across most of the disk surface could play a very important role.”

Related: James Webb Space Telescope finds supernova ‘Hope’ that could finally resolve major astronomy debate

The team’s research was published on Friday (Oct. 4) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Tracking the winds of change around infant stars

It is estimated that within the portion of the cosmos that humanity is capable of seeing, a staggering 3,000 stars are born every second. In their infancy, those stellar bodies are referred to as “protostars,” and they are surrounded by a prenatal cocoon of gas and dust, from which they formed.

Over time, this cloud flattens as it swirls around the protostar, which feeds from it to gather enough mass to kick-start the fusion of hydrogen to helium at its core. This process defines what is a main sequence or “grown-up” star.

However, in order for the protostar to feed and grow, the gas swirling around it must lose angular momentum. If it didn’t, it would simply continue to spin around the protostar in perpetuity, suspended and never falling to its surface.

Yet, despite how ubiquitous this process must be in the cosmos, scientists have struggled to understand the mechanism behind the loss of inertia. One suggestion that has gained support recently is that winds driven by magnetism raging through the protoplanetary disk could funnel gas from its surface, carrying away angular momentum.

Team member Tracy Beck, a researcher at NASA’s Space Telescope Science Institute, pointed out that because other mechanisms are at work generating winds in protoplanetary disks, it was key for the team to distinguish between these processes.

For instance, a protostar’s magnetic field creates an “X-wind” that pushes out material at the inner edge of the protoplanetary disk. In the meantime, intense radiation from the baby star blasts material in the outer parts of the disk, causing it to erode and create “thermal winds.” These latter winds blow at slower speeds than X-winds, which can travel dozens of miles per second.

In addition to being faster, X-winds arise farther from the central protostar than thermal winds. They are also capable of stretching out farther above the disk than thermal winds, reaching distances equal to hundreds of times the distance between Earth and the sun.

Fortunately, the incredible sensitivity and high resolution of JWST’s infrared vision are ideally suited to distinguish between magnetic field-driven winds, thermal winds and X-winds blowing around protostars.

The $10 billion space telescope was aided in the investigation by the team’s selection of protostar systems that are edge-on when seen from Earth. That orientation means that the dust and gas in the protoplanetary disk acted as a natural shield, blocking starlight from the protostars, preventing JWST from being dazzled, and allowing it to distinguish between the winds.

Without this hindrance, the team was able to use JWST’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) to trace distinct atoms and molecules as they traveled across these protoplanetary disks. Using NIRSpec’s Integral Field Unit (IFU) then allowed them to build an intricate 3D picture of the structure of a central jet within a cone-shaped envelope of disk winds. This envelope was structured like an onion, made of layers originating at progressively greater radii in the disk.

The team discovered pronounced central holes in these cones formed by winds in each of the four protoplanetary disks.

The researchers now aim to study other protoplanetary disks in an attempt to discover if these holes are common. They can then attempt to determine what role they may play in feeding infant stars.

“We believe they could be common, but with four objects, it’s a bit difficult to say,” Pascucci concluded. “We want to get a larger sample with JWST and then also see if we can detect changes in these winds as stars assemble and planets form.”