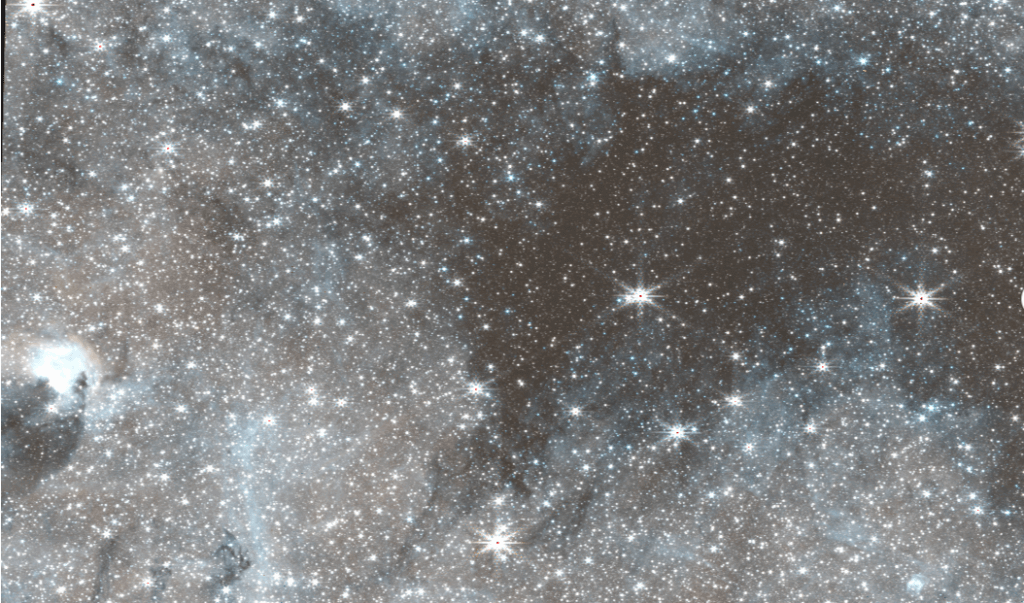

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has detected a substantial abundance of carbon-monoxide ice in a giant cloud of molecular gas, nicknamed “The Brick,” that sits near the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

The Brick — which has a proper designation of G0.253+0.016 — resides in what astronomers refer to as the Central Molecular Zone, a huge agglomeration of nebulas totaling 60 million times the mass of our sun.

Many of these clouds are busy forming stars, but The Brick got its name because it is a dark slab set against the furnace of the Galactic Center. Why The Brick has yet to really start forming stars remains a mystery. One possible explanation is that it is a young cloud that hasn’t had a chance to form stars yet; another is that gas within The Brick is too turbulent, or is being propped up and therefore prevented from collapsing by magnetic fields. It is such gaseous collapse that typically leads to star formation.

Now, the JWST has deepened the mystery even more. The spaceborne observatory has discovered a ton of carbon-monoxide ice in The Brick.

Related: Earth-like planets may form even in harsh environments, James Webb Space Telescope finds

Carbon-monoxide ice has been detected in the Galactic Center before, condensing on particles of dust, but it is generally difficult to detect in the interstellar medium. Therefore, no one really knew how much ice is in the nebulas at the center of the galaxy. That’s why astronomers led by Adam Ginsburg of the University of Florida were surprised when the JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) detected so much of the substance.

“Our observations compellingly demonstrate that ice is very prevalent there, to the point that every observation in the future must take it into account,” said Ginsburg in a statement.

Star formation requires very cold conditions to begin, with molecular gas plunging to temperatures as low as ten degrees above absolute zero. Absolute zero, for context, is the lowest possible temperature in the universe. However, despite the ice’s abundance, the JWST measured that gas in The Brick is surprisingly warm compared to other molecular clouds.

The next step, the team says, is to use the JWST to discover what other ices are to be found in The Brick and other nearby nebulas in the Galactic Center.

“We don’t know, for example, the relative amounts of carbon monoxide, water and carbon dioxide, and complex molecules,” said Ginsburg. “With spectroscopy, we can measure those and get some sense of how chemistry progresses over time in these clouds.”

Studying the center of our galaxy may have cosmological repercussions. Star-forming conditions in general in the Galactic Center are thought to be our closest mirror of the star-forming conditions in the early universe. Some theories also suggest supermassive black holes were born from the gravitational collapse of extremely massive molecular clouds. However, one spanner in the works of this theory has always been the mystery of what prevented the collapsing clouds from fragmenting and forming lots of stars rather than one black hole. Clues to the answers might be found in the opaque confines of nebulas like The Brick.

The new findings were published on the Dec. 4 in The Astrophysical Journal. A preprint is available here.