Avi Loeb is back.

The former chair of the Harvard Astronomy Department recently returned from an expedition to the Pacific Ocean near Papua New Guinea that dragged a magnetic sled across the seafloor in an attempt to find fragments of what Loeb claims is the first-known interstellar meteor, what he refers to as “IM1.”

This space rock, measuring roughly 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) in diameter, exploded above the Pacific Ocean on Jan. 8, 2014. By following the path of the meteor with the sled, Loeb hoped to find fragments of the rock, which could then be analyzed to determine if their chemical composition could confirm them as being interstellar in origin.

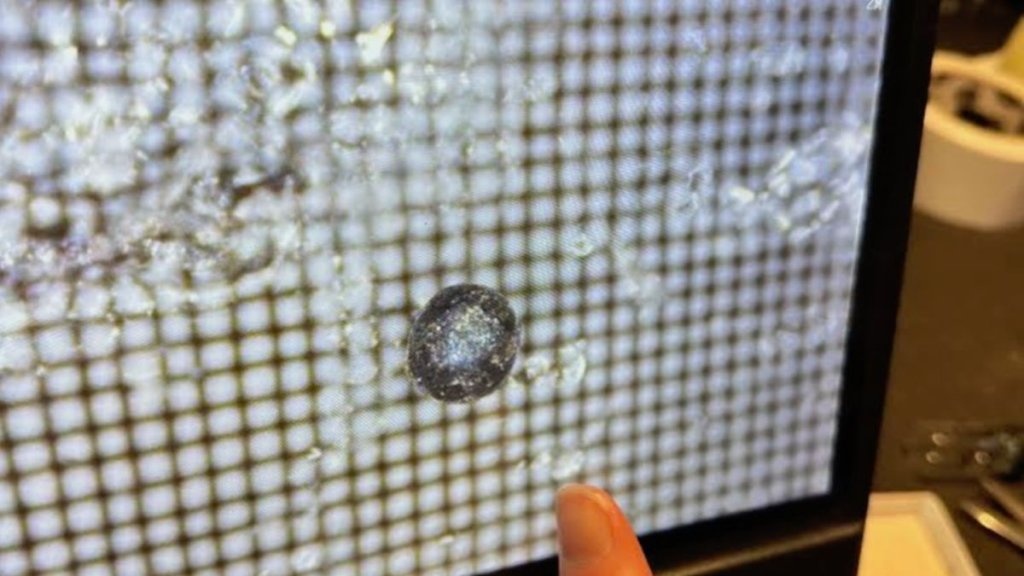

As it turns out, the expedition turned up dozens of tiny metallic spheres, or spherules, less than a millimeter in diameter. In a July 3 blog post titled “Summary of the Successful Interstellar Expedition,” Loeb stated definitively that “we did it.” The discovery of these spherules, Loeb wrote, “opens a new frontier in astronomy, where what lay outside the solar system is studied through a microscope rather than a telescope.”

While Loeb believes he has found evidence of the first interstellar meteorite, others have their doubts. And the debate is turning ugly.

To find any possible fragments from the airburst that landed on the seafloor, Loeb’s expedition dragged its magnetic sled along the path of the meteor, and did the same in a control region outside of that path. In the July 3 blog post, Loeb claims that the composition of the spherules found inside the path of the meteor “are consistently from the same source, whereas the background spherules from the control region had a different morphology and composition.” This, Loeb claims, shows that these tiny spheres trace back to the 2014 fireball that reportedly came from interstellar space.

In both public statements and an interview with Space.com, Loeb suggests that the basis for his expedition, which was funded exclusively by cryptocurrency entrepreneur Charles Hoskinson, was a 2022 memo from the United States Space Command stating that data available to the Department of Defense (DOD) is “sufficiently accurate to indicate an interstellar trajectory” for the 2014 meteorite.

However, some say that making the leap from that memo to the spherules Loeb recovered isn’t possible. Phil Metzger, a planetary scientist at the University of Central Florida, wrote in a July 16 Twitter post that “connecting that meteor to a few tiny balls of metal taken from a vast area of ocean floor isn’t a capability of the Space Command.”

Echoing that, Matthew Genge, a planetary scientist at Imperial College London who specializes in meteorites, said that connecting the spheres with the 2014 fireball — or any meteorite fragments with any other meteor — is impossible. “Meteorite ablation debris has been found, but not from an instrumentally observed fireball,” Genge told Space.com via email. “There never has been a micrometeorite derived from a specific fireball event, and never will be, since it is an impossibility.”

Peter Brown, an astronomer at the University of Western Ontario, agreed with Genge. If the meteor did in fact enter Earth’s atmosphere at the speeds reported, Brown said, it would have been vaporized into fragments much smaller than the spherules Loeb’s expedition discovered.

“There has never been a meteorite recovered from any object that hits the atmosphere moving at more than 28 kilometers a second [62,600 mph],” said Brown, who studies meteors and small solar system bodies such as asteroids. “Any solids that would remain would be essentially aerosol-size.” (In a 2022 paper in The Astrophysical Journal, Loeb claimed that IM1 was moving between 52 and 58 km per second, or 116,000 to 130,000 mph.)

Uncertain data

Aside from the difficulties in connecting the fireball event to the spherules found on the ocean floor, there are significant doubts about the accuracy of the data that underpin Loeb’s claims to begin with.

For one, all sensors, whether ground-based or in space, have margins of error or uncertainty. For many scientific instruments, these levels of uncertainty are known, allowing scientists to take them into account when analyzing the data they produce.

When it comes to the sensors the DOD used to measure the speed and trajectory of the alleged interstellar meteorite, those uncertainties aren’t published publicly due to the fact that the U.S. government does not disclose the capabilities of many of its space-based assets.

However, there are public data sets that incorporate measurements from these sensors that can be compared with those made by other sensing stations, allowing researchers to have a rough estimate of the levels of uncertainty in these U.S. government sensors.

That’s according to Brown, the co-author of a recent paper accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal that calls into question the data supporting an interstellar origin for the 2014 fireball that Loeb claims is responsible for the spherules he recovered from the ocean floor.

Brown told Space.com that, as a result of the finite sampling rate of U.S. government systems such as those used to measure the velocity of the fireball, speed estimates are “systematically overestimated, particularly at higher speeds.”

Brown pointed out that in the light curve recorded by the U.S. government (a graph of luminosity over time), the January 2014 fireball displayed four distinct flares as it entered the lower atmosphere, but there was “no evidence earlier in the record of any sort of luminosity.”

“And this is a key point,” Brown said. “It’s very difficult to get an object that purportedly is moving 45 kilometers a second [100,700 mph] down to 18 kilometers [11 miles] altitude, without producing lots of light higher up. It’s in fact almost impossible, unless you have something that’s extremely strangely shaped. It would have to be very aerodynamic, very low drag, very high density — not iron — and then you have to explain why it suddenly detonates into small particles at 18 kilometers altitude.”

All of these assumptions would be incredibly difficult to reconcile at once, Brown said — unless the direction and/or speed measurements reported by the U.S. government have similar error levels that are consistent with the larger data sets produced by the same sensors. In that case, the meteor’s speed could be considerably lower than Loeb’s estimate. And if that’s true, Brown said, “the object becomes bound. It’s no longer interstellar.”

Loeb, however, told Space.com that Brown’s paper and the criticism of his claims within it are likely just academic mudflinging. The composition of the spherules alone, he says, prove that they stem from the fireball.

“And now this paper comes out on the day that I’m back from the expedition and says, ‘No, the government is wrong. And by the way, the composition shows this object is not interstellar. Its speed was miscalculated, or not measured well, and it’s actually three times slower, and it cannot be made of iron,'” Loeb said.

“Yet I hold in my hand the vials with the spherules from this meteor, because most of them were from the meteor path, and then they show the composition is mostly iron,” he added. “So that’s, you know, that is the kind of pushback from people that are preferring to have an opinion before looking at or seeking evidence.”

‘Betraying the profession’

Aside from disagreements about the accuracy of data, Loeb’s claims have been controversial for other reasons. His expedition has drawn criticism for essentially stealing the fragments by not securing the proper permits from the government of Papua New Guinea. In addition, no women were present on the expedition.

Some astronomers also see Loeb’s bold claims as an embarrassment for their field. In a blog post dated July 18, Pennsylvania State University astronomer Jason Wright, director of the Penn State Extraterrestrial Intelligence Center, wrote that Loeb’s “shenanigans have lately strongly changed the astronomy community’s perceptions of him” and that “Loeb’s work is unambiguously counterproductive, alienating the community working on these problems and misinforming the public” about the search for possible extraterrestrial intelligence.

For his part, Loeb finds the criticism odd. “Science is supposed to be just based on evidence, not on opinions that have no substantiation,” he said. “So if someone says, ‘I’m going out to seek some evidence,’ it should be all positive. Why would you have any reservations if you call yourself a scientist? I mean, you can call yourself a scientist and just have your own belief system, but then you’re betraying the profession.”

Despite all of the criticism, Loeb remains undaunted as he presses forward with analyses of the spherules his expedition recovered. “Science should not be diminished based on the superficial undertones in social media and academic jealousy. And that’s a natural tendency, basically, stepping on any flower that rises above the grass level. A lot of people prefer that.”

Avi Loeb’s upcoming book from Mariner Books, “Interstellar: The Search for Extraterrestrial Life and Our Future in the Stars,” will be available on Aug. 29, 2023.