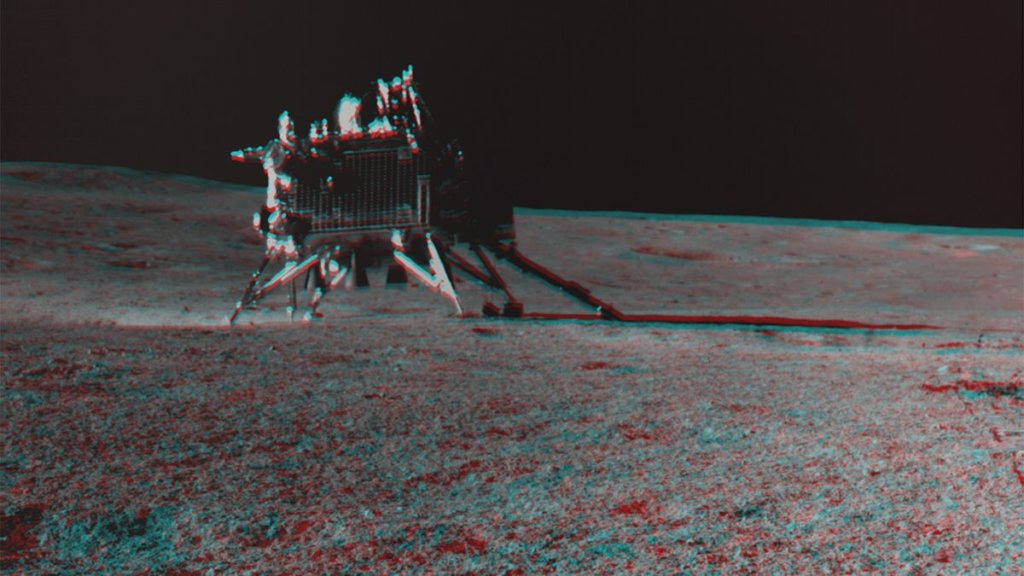

After a groundbreaking two-week mission, India’s robotic explorers are fast asleep in the frigid darkness of the moon’s south pole region. Whether they’ll wake up when the sun shines down on them at the end of this lunar night mostly whittles down to luck.

Temperatures near the moon’s poles can drop to as low as -424°F (-253°C or 20 K). Yet neither Chandrayaan-3’s lander, Vikram, nor its rover, Pragyan — which made a historic touchdown on Aug. 23 — are equipped with heaters otherwise common for moon missions.

These heaters, called radioisotope heater units (RHUs), work by passively radiating heat to keep the hardware onboard spacecraft at sustainable operating temperatures. Most commonly, RHUs used in space missions convert heat generated from the natural decay of radioactive versions of plutonium or polonium into electrical power. This process ultimately warms spacecraft hardware, though mostly just enough to help it survive very cold temperatures.

But without such power systems, the survival of Chandrayaan-3‘s robotic duo is left to chance.

Related: Chandrayaan-3 rover and lander in sleep mode but might wake up later this month

Weighing the chances

RHUs have been used in moon landing missions since the 1970s.

Lunokhod 1, which was the first successful lunar rover that covered over 10 kilometers (6 miles) in just 10 months, had powered itself using solar cells mounted on a large lid. During nights on the moon, it closed that lid to keep itself warm until the next sunrise with the energy supplied by a polonium-210 radioisotope heater.

China’s Chang’e-3 lander and rover duo, which landed not too far off from Lunokhod 1’s site in a large crater on the northwest part of the moon in 2013, had similar mechanisms onboard to protect it from bitter lunar nights. The rover, Yutu, survived the first night but permanently lost its mobility after the second. For the past four years, however, its six-wheeled successor named Yutu-2 has woken up as expected on each lunar day.

ISRO hasn’t publicly discussed why similar radioisotope heaters were not fitted onboard Chandrayaan-3’s Vikram lander and Pragyan rover – nevertheless, the robotic duo splendidly accomplished its science goals in a region of the moon that has firmly become a hotspot for space exploration, thanks to apparently harboring reservoirs of frozen water. In fact, it was the first to successfully land there at all.

— Why Chandrayaan-3 landed near the moon’s south pole — and why everyone else wants to get there too

— India’s Chandrayaan-3 landed on the south pole of the moon − a space policy expert explains what this means for India and the global race to the moon

— India tests parachutes for Gaganyaan crew capsule using a rocket sled (video)

The lander even exceeded its mission objectives when it managed to “hop” on the moon’s surface, flinging itself upward by about 16 inches (40 centimeters) and a tad closer to its companion Pragyan, which had already been put into sleep mode at that point.

As for preparing the robotic duo for its first lunar night, the batteries onboard Chandrayaan-3’s rover Pragyan were fully charged before it was put to sleep, the Indian Space Research Organization, India’s space agency operating this mission, said in a post on X (formerly Twitter).

“After sunset, there is no power,” Arun Sinha, a former senior scientist at ISRO, told Space.com prior to Chandrayaan-3’s launch. “However, there are faint chances of extra-efficient battery charge. If this is good, another 14 days might be available.”

“Else, it will forever stay there as India’s lunar ambassador,” ISRO said Sept. 2 in a post on X.