A ridge etched into the ice sheet of Greenland provides an unexpected hint that plentiful pockets of water may be trapped just underneath the surface of Jupiter’s ice-covered moon Europa, one of the solar system’s likeliest candidates to host microbial life.

The surface of Europa, one of Jupiter‘s four main moons, is covered with a 15-mile-thick (20 kilometers) ice crust, underneath which scientists believe an ocean swashes. But there might be scientific promises much closer to the frozen moon’s surface, according to a new study that found similarities between processes shaping the surface of the distant moon and Earth‘s own icy Greenland.

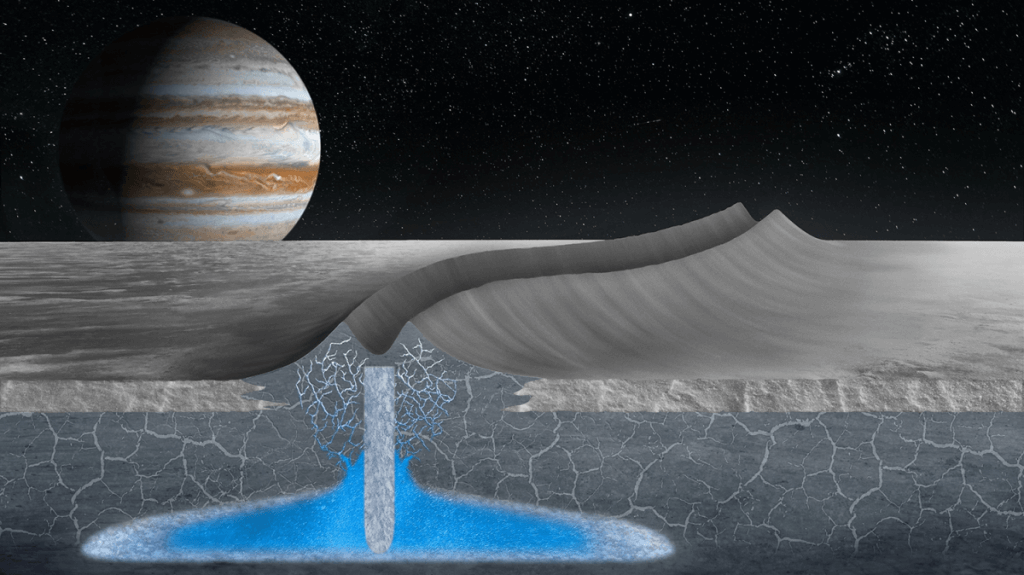

Europa’s ice crust is latticed with so-called double ridges, pairs of long parallel raised lines with a vale in between, as much as hundreds of miles or kilometers long. Every sector of the moon’s surface is marked with a criss-crossing array of these double ridges, but scientists have never been quite sure how they form.

Related: ‘Chaos’ regions of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa may increase chance for life

But a recent analysis of satellite images revealed that a strikingly similar ridge formed in the ice sheet covering Greenland about 10 years ago.

“This is the first time that we’ve seen a double ridge like this on Earth,” Riley Culberg, a graduate student at Stanford University and a lead author of the new study, told Space.com.

By studying what lies under that Greenland double ridge, Culberg and his colleagues have theorized that double ridges — both on Earth and on Europa — are formed by underground water surging up through cracks in the surface ice, then refreezing. If the explanation is correct, it’s a hint that Europa might have more than just a deep hidden ocean; the Jovian moon might also hold water in pockets just under the ice’s surface.

Culberg, a geophysicist who primarily studies the impacts of climate change on Greenland’s ice sheet, saw images of Europa’s double ridges and was instantly reminded of a feature he had seen in images of Earth’s polar island. Indeed, when scientists adjust their measurements to account for the differing gravity, the shape of Greenland’s double ridge is strikingly similar to Europa’s.

That’s helpful because scientists can do to Greenland something they can’t yet do to Europa: pierce the ice’s veil using radar. And in Greenland, radar scans showed water that had welled up below the double ridge.

The scientists think that upwelling water is the key to forming double ridges. When a pool of water forms within the ice, it can start building pressure against the surface ice above. With enough pressure, the ice might crack, and water can start to flow up into the gap. That water quickly refreezes, but the pressures from this whole process carve double ridges into the surface.

It’s hard to overstate just how much of Europa is covered by double ridges. If the proposed explanation is correct, that would mean pockets of water under the surface have been a feature of Europa for much of the moon’s history. If so, something must be replenishing the water pockets.

This is where Greenland isn’t quite as good a comparison, since its double ridge formed within the past decade. Culberg and his colleagues think that an unusually warm summer in 2012 melted enough water to pool in an underground pocket under the ridge.

But there’s little meltwater to be found on Europa’s surface, so Culberg and his colleagues argued that this new water is coming from even deeper under the ice: tens of miles or kilometers deep, where scientists expect to find a worldwide ocean.

“It tells us at least that there’s a lot of cycling, maybe, between the subsurface ocean and the near surface,” Culberg told Space.com.

Finding these shallow water pockets could be a quest for future probes to Jupiter’s moon, like NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which is expected to launch in 2024. And excitingly for scientists like Culberg, Europa Clipper will carry ice-penetrating radar just like the sort the researchers used to peer under Greenland.

Culberg and his colleagues published their work in the journal Nature Communications on April 19.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.