Researchers have tested a suite of anemometers — tools that measure wind speeds — designed to operate on the surface of Mars.

These would not be the first to take the Martian wind speed, to be clear, as landers have done that for quite some time. Even Viking 1 managed to grab some Martian wind measurements nearly fifty years ago. But, according to the researchers’ findings, this system could allow future landers — or future humans — to measure Martian winds with more sensitivity than ever before.

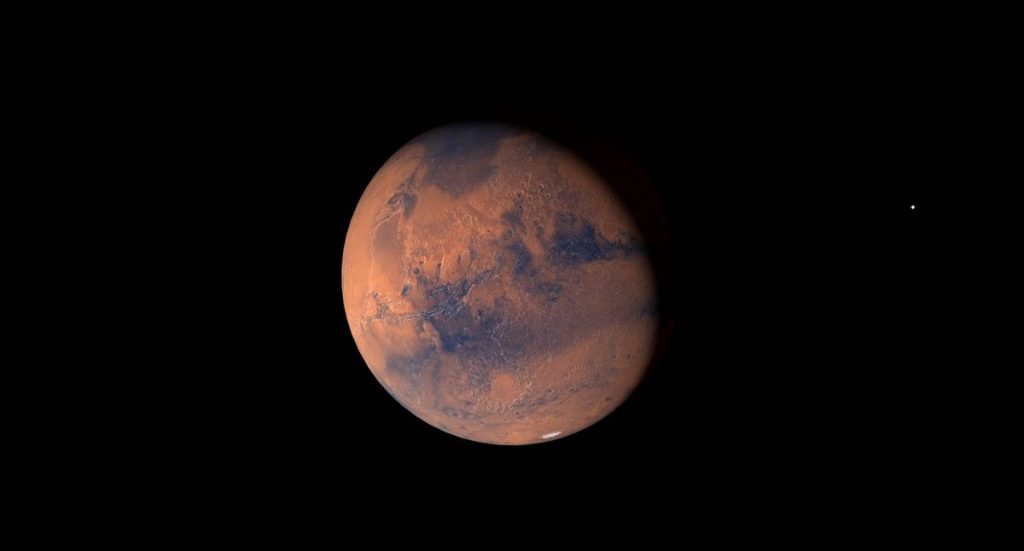

Measuring the Martian wind is not as simple as taking an anemometer from a garden-variety Earth weather station and mounting it on a Red Planet lander. For one, Mars is much colder than all but the coldest regions on Earth. For another, the Martian surface’s average air pressure is about one-one-hundredth that at Earth’s sea level.

So, Martian meteorologists must find alternative methods, like measuring how quickly a heated material cools when wind blows over it or reconstructing the speed of objects billowing in the wind. Such methods do work, but they’re comparatively slow, and they only give observers the big picture — an average wind speed — while missing smaller eddies or local turbulence blowing back or forth.

Related: Wind farms on Mars could power future astronaut bases

“This is important for understanding atmospheric variables that could be problematic for small vehicles such as the Ingenuity helicopter that flew on Mars recently,” said Robert White, a mechanical engineer at Tufts University and one of the researchers, in a statement.

White and his colleagues identified a different Earth meteorologist’s tool that seemed promising for Mars: an ultrasonic anemometer. Such a device sends ultrasound pulses from one transducer to another. As moving air blows between the transducers, it jostles the pulses and shifts how long they take to arrive. An ultrasonic anemometer can measure these shifts between multiple sets of transducers and use them to reconstruct wind speed and direction.

“By measuring sound travel time differences both forward and backward, we can accurately measure wind in three dimensions,” said White, in the statement. “The two major advantages of this method are that it’s fast and it works well at low speeds.”

The catch is that these ultrasonic anemometers rely on highly sensitive materials. Thus, the researchers tested four different ultrasonic anemometers — two off-the-shelf models and two they had built themselves — in simulated Martian air conditions. By compensating for the alien atmosphere in their reconstructions, the researchers could take wind readings within an ultra-small error range.

Interestingly, conditions on the Martian surface are comparable to those 30 kilometers to 42 kilometers (19 miles to 26 miles) above Earth’s surface. To that end, the authors believe that their device could also be mounted on a balloon and help measure winds high in Earth’s atmosphere.

The researchers published their work in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America on August 13.