As power drained from its solar limbs, the tired spaceship went quiet, spinning out of control and into exhaustion.

Reluctantly, engineers sounded the alarm for the moonbound CAPSTONE mission. NASA gave special permission to the team to use the Deep Space Network, a system of three enormous radio dishes on Earth, to place a 1-million-mile long-distance call to the little spacecraft. It was their last hope.

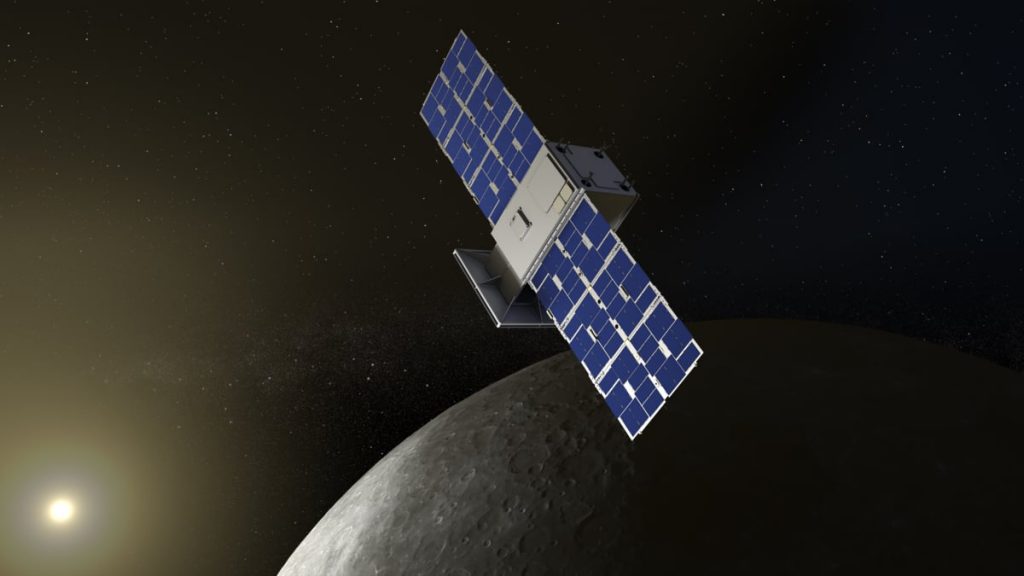

Connecting with a football field-sized antenna, Capstone — a spacecraft that could be mistaken for a winged microwave-oven — started talking again. And in so many data points, its message home was clear: It won’t be much longer for me now — I’m dying.

“Without power,” said Jeff Parker of Advanced Space, whose voice broke retelling that moment to Mashable, “geez, I even get choked up about it. Without power, the spacecraft was freezing.”

“Without power, the spacecraft was freezing.”

Few know the tale of the first true mission of Artemis, NASA’s new moon program, and how it crawled back from the edge of death in September 2022, only to survive and achieve an unprecedented feat two months later.

This wasn’t Artemis I, by the way, the maiden voyage of a new passenger spaceship in November from the same famous Florida coastline that pitched Apollo astronauts to the moon. No, this one took off four months earlier, 8,000 miles away, on a sparsely populated headland in the southwestern Pacific, where pastured sheep and cattle might occasionally raise their snouts to see a rocket graze the sky.

CAPSTONE [Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment] — a lunar mission with a tiny spaceship that goes by the same name — launched aboard a Rocket Lab Electron rocket from Mahia, New Zealand, on June 28, 2022.

Its raison d’etre was to scout an orbit around the moon no other spacecraft has ever flown. That path is key to NASA’s ambitious plan to put a crewed space station at the moon for Artemis, starting in 2024 or thereabout. The outpost, to be called Gateway, would serve as a base for astronauts going back and forth to the moon’s surface.

In a departure from business as usual, NASA doesn’t own or operate this little 55-pound ship. The agency chose to partner with private companies on the mission to lower costs and get to the launch pad quicker. Terran Orbital built it, Advanced Space owns and manages the mission from Westminster, Colorado, and Rocket Lab shot it into space. From soup to nuts, the entire project cost $30 million, a pittance compared to the more than $4 billion spent on a flagship mission like Artemis I.

Gateway’s orbit around the moon

The unusual trail it was built to blaze, known as a near-rectilinear halo orbit [NRHO], looks like a necklace hung from the moon, draping around its north and south poles. Imagine a close hug where the necklace would clasp, about 1,000 miles above the lunar surface, then a deep 40,000-mile scoop away from the moon at the bottom. The flyby at the top is like receiving a lunar gravity boost once a week. All the while, any spacecraft on the route would continuously face Earth, allowing for constant communication.

“That’s a new maneuver that we have to do that we’ve never done before,” said NASA administrator Bill Nelson to reporters last year. “And remember, Apollo went into equatorial orbit. This one’s going into polar orbit.”

Scientists considered many potential orbits before deciding this one was the best fit for a future space station. A low-lunar orbit, for example, would circle very close to the moon’s surface. That would put the base closer to the ground but would require a lot more fuel to counteract the moon’s gravity. A distant retrograde orbit, on the other hand, would be more stable and require less fuel but would be less convenient for accessing the ground. Gateway’s proposed orbit is the Goldilocks solution, combining the benefits of both.

Credit: Rocket Lab

That’s where Capstone comes in, soaring ahead, seeking out any bumps on the trail before a bigger spaceship carrying humans arrives.

“Would you fly this multibillion-dollar Gateway in a unique orbit with only paper studies, or would you feel more comfortable if a spacecraft has already demonstrated that you can do it?” Parker asked rhetorically.

What went wrong with Capstone?

Credit: Rocket Lab

For two months, Capstone’s solo journey was spotless, uneventful, barely noticeable. To save on fuel, it traveled a scenic route, moseying into a special transfer maneuver that would take four months to reach the moon.

It wasn’t until a routine course correction that something cataclysmic happened.

Any space journey has navigation errors. Just as a person in a car adjusts the steering wheel while driving, so do spacecraft. But at the end of this planned engine firing on Sept. 8, 2022, one thruster wouldn’t stop burning.

It only took an instant for a fault protection system to kick in and shut the whole propulsion system off. But those extra four seconds of thrust were enough to send the spaceship rolling.

Capstone spun fast — a full turnabout every five seconds — with no end in sight.

As best as anyone could surmise, a tiny piece of debris must have gotten trapped in a thruster valve at some point, preventing one from closing.

During each rotation, the ship’s solar panels were only intermittently pointed in the right direction to soak up the sun’s rays. Eventually, Capstone was not making enough power to replenish its batteries. So mission engineers watched their spacecraft slip in and out of consciousness, over and over, about once every hour.

Turn on. Phone home. Shut off. Recharge. Turn on. Phone home. Shut off. Recharge.

They’d see Capstone’s signal but didn’t have enough time with it to collect helpful information.

“We couldn’t communicate with it worth a darn,” said Parker, who admits to his affection for the scrappy box of mixed metal and circuits. He is one of several CAPSTONE mission operations managers, a title befittingly shortened over control room chatter to “Mom.”

Credit: NASA / Dominic Hart

Parker felt something akin to a mother’s despair when the Deep Space Network finally made contact with Capstone and learned the spaceship’s vitals. Its temperature had dropped to minus 7 degrees Celsius. Its tank was frozen. Game over, he feared.

“They’re robots,” he said of spacecraft like Capstone, “but, you know, you give them a name and sometimes even a gender and then you start to get attached to them.”

“They’re robots, but, you know, you give them a name and sometimes even a gender and then you start to get attached to them.”

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

How Capstone stopped spinning

Without many choices, the team intentionally eased Capstone into a coma, turning off all of its systems so it could conserve power.

For days, it slept, and they waited.

Then, mission controllers tried waking it up, flipping on just one heater to thaw the fuel tank. Gradually, they convinced themselves they could turn on another heater, and so on. Over a week, they slowly warmed Capstone to a normal temperature.

The team tried clearing the stuck valve. Engineers issued repetitive, stern commands, hoping they could jiggle the clog loose: Open! Close! Open! Close!

Nothing worked, and in flicking it on and off, they actually caused the ship to spin at a more dizzying clip.

That meant they were going to have to learn to live with a bum thruster that would never stop firing as long as the propulsion system was on. So they learned to work with the handicap. A guidance and navigation team built a new controller for the spaceship using its data and computer simulations: If one thruster was never going to stop, they’d strategically fire a couple of other thrusters at the same time to overpower it.

Now it was time to test the new controller on the real thing. On Oct. 7, 2022, Advanced Space executed the recovery operation. And just like that, a month after the tumbling began, the death spiral was over.

“Would you fly this multibillion-dollar Gateway in a unique orbit with only paper studies, or would you feel more comfortable if a spacecraft has already demonstrated that you can do it?”

Was the Capstone mission successful

Since then, Capstone has thrived, reaching its unique orbit on Nov. 13, 2022, just before NASA’s mega moon rocket blasted Orion into the sky. There it will stay for up to 1.5 years, gathering data for NASA and testing some new onboard devices: GPS software and a computer chip-scale atomic clock. Both could be used to help spaceships at the moon find their positions without having to rely on precious resources from the Deep Space Network in the future.

After the little spaceship finishes its primary mission, it could either stay at the moon and continue navigation experiments or do what most yearn for in retirement: see the world. In this case, rather, other worlds.

Who knows, Parker muses? Maybe even visit an asteroid.

The spaceship’s life might have been cut a bit shorter by its brush with death, but Capstone’s many moms believe its best years are ahead of it.

“Even in the darkest moments, when you learn that you’re flying a frozen-solid spacecraft, and it’s spinning out of control,” said Parker, “you still hold out hope.”