While space travel sucks out red blood cells and weakens bone, all is not lost in microgravity.

Fatty tissue inside your bones acts as a stopgap against declining cells and bone density in weightlessness, a new study of International Space Station (ISS) astronauts suggests. Better yet, treatments based on this new knowledge may help aging populations — as well as folks on Earth who must stay in bed due to medical conditions.

“We found that astronauts had significantly less fat in their bone marrow about a month after returning to Earth,” senior study author Guy Trudel, a rehabilitation physician and researcher at The Ottawa Hospital and professor at the University of Ottawa, said in an Aug. 21 statement. (The lead study author is Tammy Liu, who is also with the hospital.)

“We think the body is using this fat to help replace red blood cells and rebuild bone that has been lost during space travel,” Trudel added.

Related: Spaceflight makes the body kill red blood cells and it doesn’t get better after landing

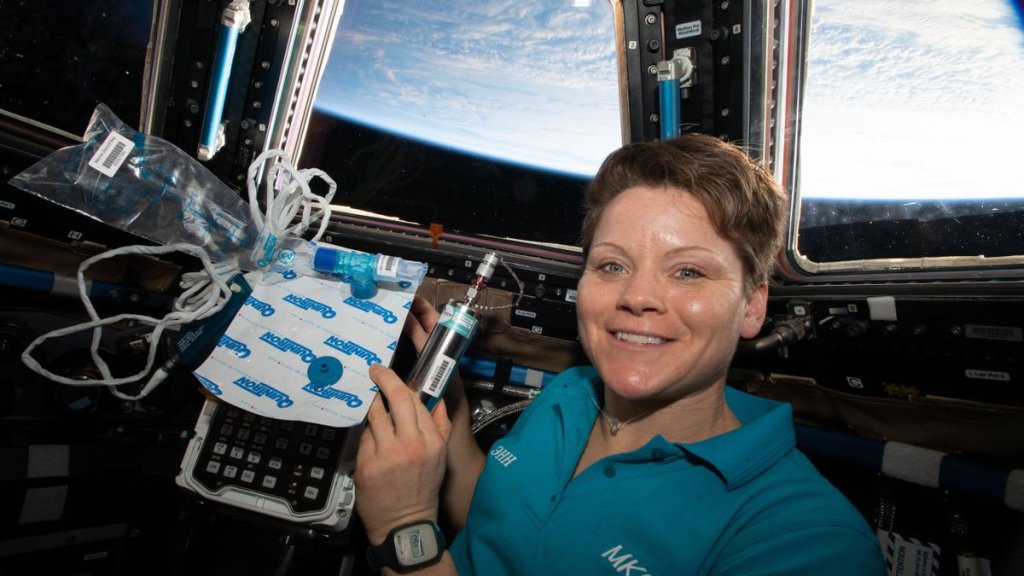

The new study examined 14 astronauts who each spent at least six months on board the ISS. It is part of a set of Canadian science seeking more information on how bone marrow and blood production change in space. One function of the ISS more generally is to study how long bouts of microgravity affect all aspects of health, from balance to bones, which is where the research fits in.

Trudel’s larger study, called Marrow, examines the bony cells that produce fat, red blood cells and white blood cells. The study wrapped up active collection of samples in 2020 but continues to push new frontiers in science as data is parsed. For example, an investigation published in 2022 tracked changes in red blood cells in space that appear to persist for some time after landing.

Red cell production is key to human health, as healthy red blood cells carry oxygen throughout the body. Without enough of these cells, the body will get anemic and experience issues with both physical and mental health. For astronauts tasked with landing on the moon or Mars, preventing this condition from happening is essential in helping to set up settlements off Earth — which NASA wants to do with its lunar Artemis program later in the decade.

“Thankfully, anemia isn’t a problem in space when your body is weightless, but when landing on Earth and potentially on other planets or moons with gravity, anemia would affect energy, endurance and strength and could threaten mission objectives,” Trudel said. “If we can find out exactly what’s controlling this anemia, we might be able to improve prevention and treatment.”

The new study of bone marrow, based on MRI scans on Earth before and after the astronauts’ space missions, showed a slight decline in bone marrow fat: roughly 4.2% more, on average, just before the astronaut flew into space, compared with a sample collection one month after landing.

This shortfall does recover on Earth, however, as red blood cells and bone density increase. Younger astronauts may be able to take more energy from the fat, while female astronauts saw more fat in the bone marrow than expected after a year, the study authors note.

“Since red blood cells are made in the bone marrow and bone cells surround the bone marrow, it makes sense that the body would use up the local bone marrow fat as a source of energy to fuel red blood cell and bone production,” Trudel said. “We look forward to investigating this further in various clinical conditions on Earth.”

A study based on the research was published in the journal Nature Communications on Aug. 9. Funding was provided in part by the Canadian Space Agency, which got the science on board ISS through its ongoing Canadarm robotics program for NASA that exchanges science and astronaut time for hardware.