Europe’s planned Venus exploration mission will depend on a challenging aerobraking procedure to lower its orbit, which will test the thermal resiliency of the spacecraft’s materials to their limits.

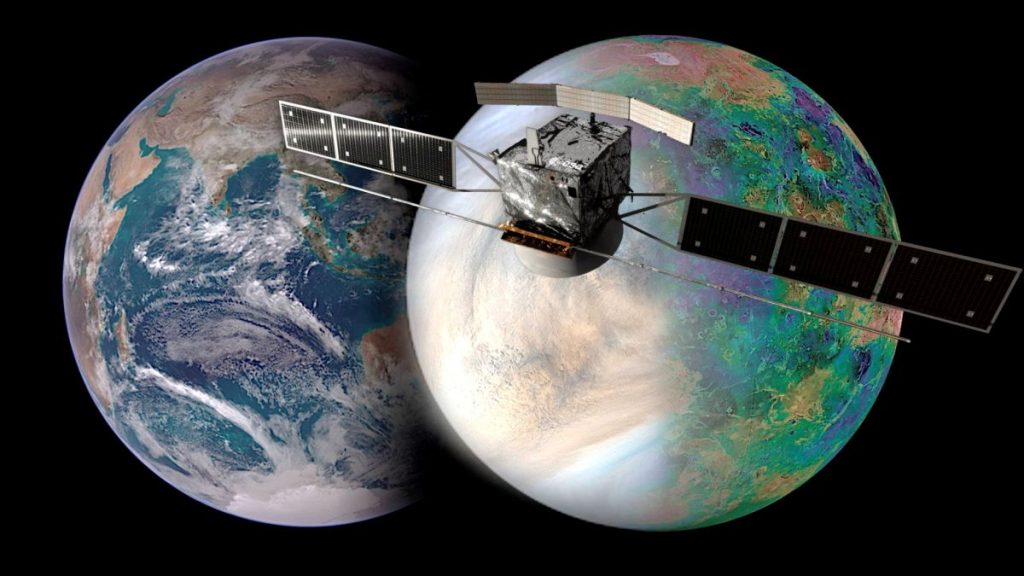

The EnVision mission, expected to launch in the early 2030s, will study the geology and atmosphere of Venus, the hellish planet that once may have looked quite like Earth but turned into a scorched hostile world due to a runaway greenhouse effect.

To get EnVision to its target orbit, 310 miles (500 kilometers) above Venus’ surface (which is so hot that it would melt lead), will take thousands of passes through the planet’s thick atmosphere over a period of two years, the European Space Agency (ESA) said in a statement (opens in new tab).

“EnVision as currently conceived cannot take place without this lengthy phase of aerobraking,” ESA’s EnVision study manager, Thomas Voirin, said in the statement.

Related: How Venus turned into hell, and how Earth is next

The van-sized spacecraft, which will launch on Europe’s future Ariane 6 rocket, will not be able to carry enough fuel to slow itself down in Venus’ orbit using onboard propulsion. Instead, it will use the aerobraking procedure and follow a highly elliptical orbit that will take it periodically to within 80 miles (130 km) of Venus’ surface at its closest and about 155,000 miles (250,000 km) from the planet at its farthest point.

ESA previously used aerobraking to slow down the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter before it entered its scientific orbit around Mars. But Mars’ atmosphere is much thinner than that of Venus, and its gravity is much lower, which affects the speed of the orbiting spacecraft.

“Aerobraking around Venus is going to be much more challenging than for Trace Gas Orbiter,” Voirin said. “The gravity of Venus is about 10 times higher than that of Mars. This means velocities about twice as high as for TGO will be experienced by the spacecraft when passing through the atmosphere, and heat is generated as a cube of velocity.”

ESA briefly tested aerobraking around Venus during the final months of the Venus Express mission, which eventually spiraled toward the planet and burned up in the atmosphere in 2014. As Venus Express was already at the end of its mission, spacecraft controllers didn’t worry about the damage sustained by the spacecraft caused by the heat. EnVision, on the other hand, will be expected to explore Venus for at least four years.

Engineers are already busy working out the right materials that would enable EnVision to withstand the extreme conditions. In addition to the heat experienced during the aerobraking procedure, the spacecraft will also be exposed to very high concentrations of highly reactive atomic oxygen. Atomic oxygen is a form of oxygen present in the upper layers of Earth’s atmosphere, which consists of a single oxygen atom. Atomic oxygen, a nemesis of all low Earth orbit spacecraft, burned thermal blankets on several NASA space shuttle missions in the 1980s.

Observations by previous Venus missions showed that atomic oxygen is present in the upper layers of Venus’ atmosphere at concentrations similar to those around Earth.

“The concentration is quite high. With one pass it doesn’t matter so much, but over thousands of times it starts to accumulate and ends up with a level of atomic oxygen fluence we have to take account of, equivalent to what we experience in low Earth orbit, but at higher temperatures,” Voirin said.

ESA is currently testing materials for their ability to withstand both the heat and the concentration of atomic oxygen expected during EnVision’s aerobraking and hopes to have some candidate materials selected by the end of this year.

“We want to check that these parts are resistant to being eroded, and also maintain their optical properties — meaning they do not degrade or darken, which might have knock-on effects in terms of their thermal behavior, because we have delicate scientific instruments that must maintain a set temperature,” Voirin said. “We also need to avoid flaking or outgassing, which leads to contamination.”

Venus, sometimes considered Earth’s twin because of their similar sizes, has lately been somewhat sidelined by solar system explorers as the potentially more habitable Mars (which is likelier to harbor traces of life) has become the favorite. But a 2020 study that detected molecules that could be traces of living organisms in the planet’s sulfur-rich clouds sparked a new surge of interest in Venus.

In addition to Europe, NASA has plans to send orbiters to the scorching-hot planet: The DAVINCI+ and VERITAS missions, which are expected to launch between 2028 and 2030. Currently, a lone spacecraft, Japan’s Akatsuki, is orbiting Venus, studying its dense atmosphere in an attempt to unravel the mysteries of its harsh climate.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).