The European sun-observing Solar Orbiter spacecraft doubles up as a Venus explorer, providing the most detailed measurements of the scorched planet’s magnetic field to date. The data might help reveal how the solar wind changes the planet’s thick atmosphere over millions of years, scientists said.

The second planet from the sun, Venus is constantly battered by the solar wind, the stream of charged particles emanating from our star. Very little is known, however, about this interaction between Earth’s neighbor, which is known for its runaway greenhouse effect, and the solar particles, said Lina Hadid, a space plasma physicist at the École Polytechnique in Paris.

“Venus has been visited by many missions before, but none of these missions actually could measure in detail the electric field data around Venus,” Hadid told Space.com. “Also, not many of them could identify in detail the ion composition in the magnetosphere of Venus. And so [with the new Solar Orbiter measurements], for the first time, we can actually study in detail the magnetic field fluctuations and the electric field fluctuation [around Venus].”

Related: ESA’s Solar orbiter just got smacked by a coronal mass ejection

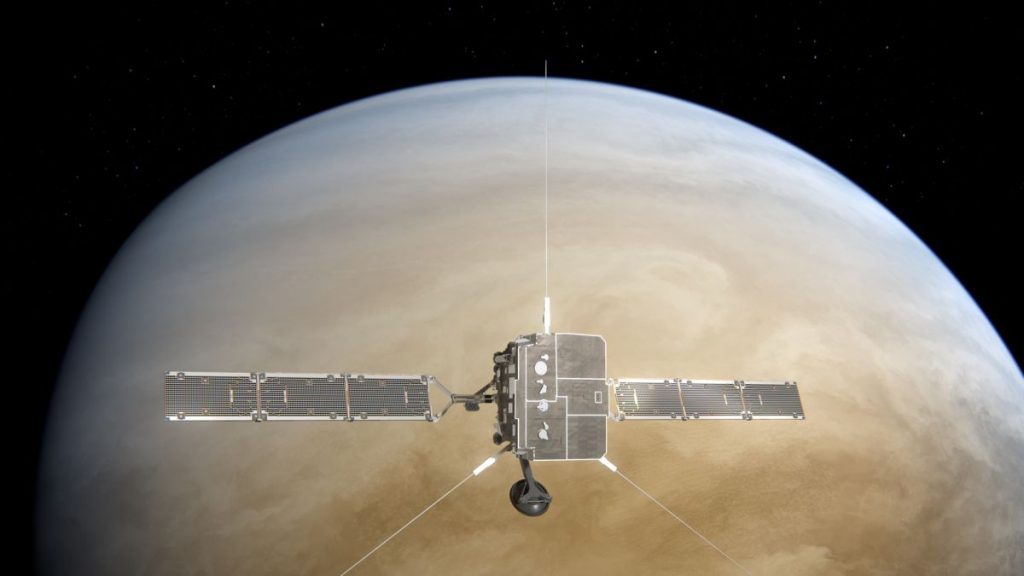

Solar Orbiter, a mission led by the European Space Agency (ESA), takes the closest-ever images of the sun. The spacecraft makes regular flybys of Venus, using the planet’s gravity to tilt its orbit out of the ecliptic plane, in which the solar system‘s planets orbit. These maneuvers will enable the probe to eventually view the sun’s poles, which play a key role in the generation of the sun’s magnetic field and therefore in maintaining the sun’s 11-year cycle of activity, the ebb and flow in sunspot creation that is responsible for space weather around Earth.

So far, Solar Orbiter has made three Venus flybys, which led to fascinating discoveries about Venus’ magnetism. Unlike Earth, Venus has no inherent magnetic field generated by the motion of molten metal in its core. The planet, however, has what scientists call an induced magnetic field, a weak magnetic shield generated by the interaction between the solar wind and the planet’s atmosphere.

During its previous flybys, Solar Orbiter found that this magnetic field extends at least 188,000 miles (300,000 kilometers) into space and could accelerate particles from Venus’s atmosphere to mind-boggling speeds of over 5 million mph (8 million kph). These supercharged particles, Hadid said, can sometimes get stripped away by the solar wind, which, over millions of years, leads to changes in the chemical composition of Venus’ atmosphere.

“With these new observations, we could see the presence of carbon dioxide molecules outside the ionosphere of Venus,” said Hadid, referring to the outer layer of the planet’s atmosphere where thin gases interact with the particles from the sun. “That means that these heavy ions of carbon and oxygen can escape from the ionosphere and get carried away by the solar wind.”

Earth’s atmosphere is protected from the worst of the solar wind battering by our planet’s much stronger magnetic field. But another solar system planet is believed to have lost its atmosphere long ago after its magnetic field weakened: Mars. Is it possible that Venus, known today for its thick clouds of sulfur dioxide and extremely high concentrations of carbon dioxide that warm the planet to over 900 degrees Fahrenheit (475 degrees Celsius), could one day look very different?

“If you observe that carbon is escaping from the atmosphere of the planet, it could allow us to estimate how much carbon this planet had, for instance, millions of years ago, and how the interaction with the solar wind led to the loss of those ions from the atmosphere of Venus over very large timescales,” said Hadid.

There is, however, too much carbon dioxide in Venus’ atmosphere — the molecule makes up over 96% of Venus’ air by volume — for the planet to become more life-friendly any time soon.

Hadid added that by studying Venus’s interaction with the solar wind and comparing it with that of Earth, planetary scientists can learn valuable lessons they could use in the future in their search for habitable planets outside the solar system.

Solar Orbiter still has five Venus flybys to go before its mission ends in the early 2030s, and that means more opportunities to study the intricacies of the solar wind’s interaction with the shroud of dense gas surrounding Venus. New missions by NASA as well as ESA are expected to visit Venus later this decade, but Hadid said there are currently no plans for these missions to carry such elaborate particle analyzers as those on board Solar Orbiter. The sun watcher might therefore still come up with many more important discoveries about the planet, which shines in our night sky as the brightest “star.”

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.