Humanity has lost an interstellar pioneer.

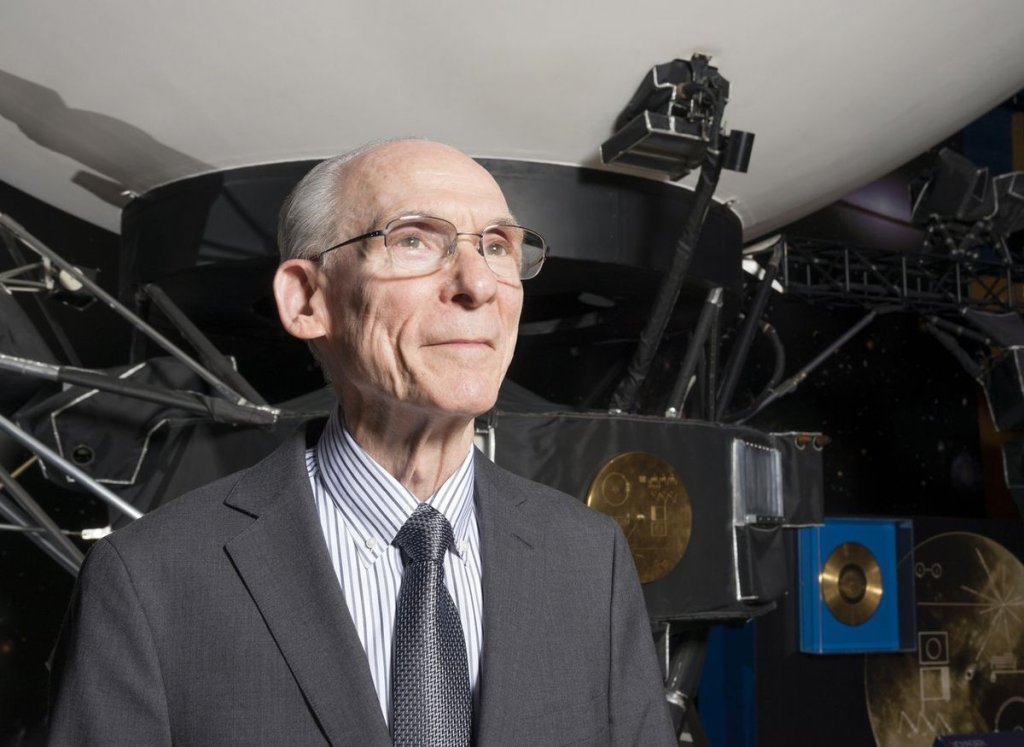

Ed Stone, who served as the project scientist for NASA’s groundbreaking Voyager mission from 1972 to 2022, died on Sunday (June 9) at the age of 88.

“Ed Stone was a trailblazer who dared mighty things in space. He was a dear friend to all who knew him, and a cherished mentor to me personally,” Nicola Fox, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said in NASA’s obituary for Stone, which the agency posted on Tuesday (June 11).

“Ed took humanity on a planetary tour of our solar system and beyond, sending NASA where no spacecraft had gone before,” Fox added. “His legacy has left a tremendous and profound impact on NASA, the scientific community, and the world. My condolences to his family and everyone who loved him. Thank you, Ed, for everything.”

Related: Going interstellar: Q&A with Voyager project scientist Ed Stone

Voyager launched twin probes on a “grand tour” of the solar system’s giant planets in 1977. The two spacecraft made many discoveries in our cosmic backyard — finding intense volcanism on the Jupiter moon Io and 10 new moons of Uranus, for example — and then kept on flying, into exciting and unexplored realms.

In 2012, Voyager 1 popped free of the heliosphere, the huge bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields that the sun blows around itself, becoming the first human-made object ever to reach interstellar space. Voyager 2, which took a different path and is moving slightly more slowly than its partner, followed suit in late 2018.

Both Voyagers remain operational today, studying the exotic environment between our star and the next. Voyager 1 is currently more than 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from home, and its twin is about 13 billion miles (21 billion km) into the void. That’s about 162 and 136 Earth-sun distances (or astronomical units), respectively.

“It has been an honor and a joy to serve as the Voyager project scientist for 50 years,” Stone said in a NASA statement in October 2022, when he announced his retirement from the role.

“The spacecraft have succeeded beyond expectation, and I have cherished the opportunity to work with so many talented and dedicated people on this mission,” he added. “It has been a remarkable journey, and I’m thankful to everyone around the world who has followed Voyager and joined us on this adventure.”

Related: Voyager: 15 incredible images of our solar system (gallery)

Stone was born on Jan. 23, 1936, in Knoxville, Iowa, according to NASA’s obituary. His father was a construction superintendent who loved showing his son how to take things apart and put them back together — and young Ed was an eager student.

“I was always interested in learning about why something is this way and not that way,” Stone said in an interview in 2018, according to NASA’s obituary. “I wanted to understand and measure and observe.”

He studied physics in junior college, then went to the University of Chicago for graduate school, where he helped build science instruments for spacecraft — still a very young field at this stage.

“The first he designed rode aboard Discoverer 36, a since-declassified spy satellite that launched in 1961 and took photographs of Earth from space as part of the Corona program,” NASA wrote in the obituary. “Stone’s instrument, which measured the sun’s energetic particles, helped scientists figure out why solar radiation was fogging the film and ultimately improved their understanding of the Van Allen belts, energetic particles trapped in Earth’s magnetic field.”

Stone became a post-doctoral fellow at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in 1964 and soon began working on NASA missions. Over the years, he served as the principal investigator or a science instrument lead on nine different agency missions and a co-investigator on five others, according to the agency.

Stone also served as director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California — the agency’s lead center for robotic planetary exploration — from 1991 to 2001. That stretch saw some major milestones, including the landing of NASA’s first-ever Mars rover, Sojourner, in 1996 with the Pathfinder mission and the launch of the Cassini-Huygens mission to Saturn (a joint effort with the European Space Agency) in 1997.

“Ed will be remembered as an energetic leader and scientist who expanded our knowledge about the universe — from the sun to the planets to distant stars — and sparked our collective imaginations about the mysteries and wonders of deep space,” JPL Director Laurie Leshin, who’s also the vice president of Caltech, said in NASA’s obituary.

“Ed’s discoveries have fueled exploration of previously unseen corners of our solar system and will inspire future generations to reach new frontiers,” Leshin added. “He will be greatly missed and always remembered by the NASA, JPL and Caltech communities and beyond.”

Stone’s colleagues have repeatedly noted his commitment to science education and communication, his genuine desire to help tell the world about scientific results in a manner both accurate and engaging.

I can attest to this commitment, for I witnessed it first-hand on multiple occasions. Despite being a very busy man, Stone was open and available to the media; he took our phone calls and stayed on after press conferences to answer more and more of our questions.

And he was unfailingly nice, polite and patient in all of these interactions. I didn’t know Ed Stone well, but I could tell he was a good man. And I, like countless others, will miss him.