Delays to the first of three missions making the long awaited return to the scorching planet Venus, which scientists say has not had enough robotic visitors in the past decades, might affect the two other missions set to explore our planetary neighbor.

Late last year, NASA pushed the VERITAS (or Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy) mission, originally scheduled to fly in 2027 to inaugurate the “Decade of Venus,” to no earlier than 2031. However, the White House’s 2024 budget proposal for NASA, announced in March 2023, holds the mission funding for VERITAS at a mere $1.5 million per year for the near future, placing the mission in a “deep freeze.” Because of NASA’s decision to use a bulk of the funding that supported the project’s engineering operations for other missions facing cost overruns, much of the work on the VERITAS mission is now at a standstill. Its indefinite delay has disbanded the mission’s engineering wing, and scientists are now worrying about its impact on two other related missions to Venus.

Related: Here’s every successful Venus mission humanity has ever launched

“VERITAS has incredible synergy with the other missions,” Stephen Kane, an astronomer at the University of California in Riverside, told Space.com.

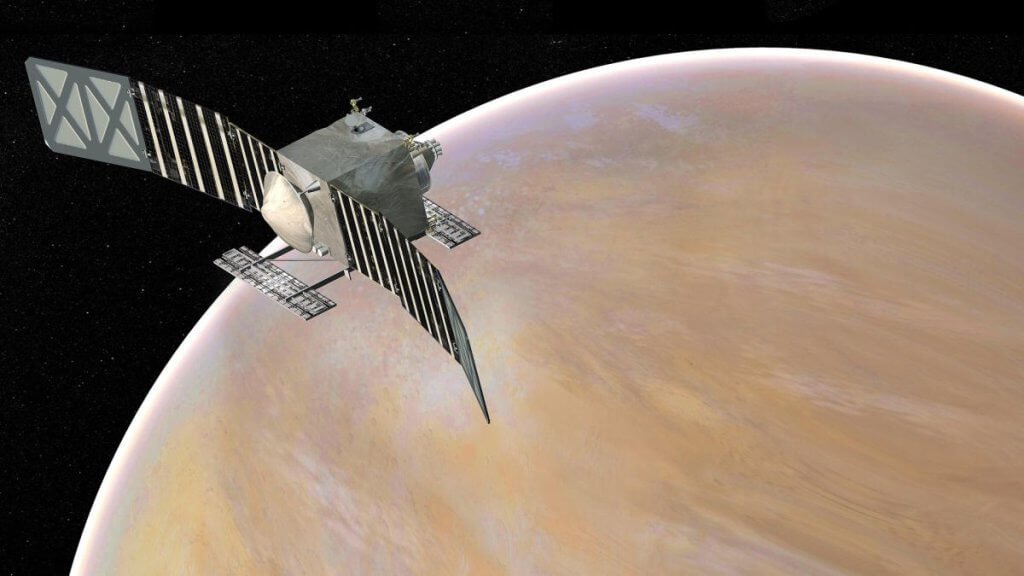

VERITAS was supposed to be the first mission to return to Venus since NASA’s Magellan spacecraft orbited it nearly 30 years ago. The spacecraft “will contribute foundational measurements needed for all types of Venus fundamental science,” Darby Dyar, VERITAS’ deputy principal investigator, told Space.com.

Some of those measurements, like mapping the surface of Venus with at at least a three-times better resolution than Magellan, were intended to support another NASA Venus mission— DAVINCI (or Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging).

Scheduled to reach Venus in early 2030s, DAVINCI will drop a probe into the planet’s thick clouds that will make its way to the surface. Per the original plan, VERITAS would have already arrived at Venus prior to DAVINCI’s launch, so scientists were hoping to use its data to select the best landing site for DAVINCI’s probe. “The surface mapping provided by VERITAS would have been incredibly useful for fine-tuning the deployment of DAVINCI,” Kane told Space.com.

Another mission originally intended to benefit from VERITAS data is EnVision, which is led by the European Space Agency (ESA) and scheduled to launch in the early 2030s to study the climate on Venus. Now, EnVision is scheduled to visit the planet around the same time that delayed VERITAS will arrive — if it survives NASA’s budget issues.

This outcome is “less than ideal when the EnVision team was hoping to have the VERITAS data already in hand,” Paul Byrne, an astronomy professor at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, told Space.com.

The parallel missions also means identical instruments on both missions would need to be built at the same time. For example, the German Aerospace Center (or DLR) is building the Venus Emissivity Mapper (VEM) for VERITAS and VenSpec-M for EnVision. Both instruments were meant to complement each other in surveying the planet’s surface, so DLR had initially planned to build VERITAS’ instrument first, and then those for EnVision.

“But with the current plan that DLR team might be building two copies of the instrument suite simultaneously,” Byrne said. “That’s going to put them under time and workforce pressure.”

Scientists are also worried that having VERITAS and EnVision at Venus concurrently will result in less than ideal output for at least some of the expected science, including now having shorter than preferred timelines for detecting Venusian volcanoes.

For example, the VEM and VenSpec-M mapping instruments on both missions will look for active lava flows on the planet’s surface, which could provide strong evidence that the planet is still volcanically active. Such findings will add to the recent discovery of an active volcano on Venus, which scientists found while sifting through 30-year-old data collected by NASA’s Magellan spacecraft.

The discovery was possible because two images clicked eight months apart showed that a volcanic vent had grown noticeably larger and also changed its shape, reflecting recent volcanic activity. Scientists hope to find similar changes with upcoming missions, which is why the arrivals of VERITAS and EnVision were staggered initially, so that their data would complement each other.

“By delaying, we reduce the separation between VERITAS and EnVision.” Darby told Space.com. “This will give a shorter timeline for detections.”

While VERITAS’ engineering team is currently standing down as directed by NASA, its science team is supported by limited funding of $1.5 million a year and continues to prepare for the mission while exploring ways to move the launch date to earlier than 2031.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.