A Japanese company’s spacecraft ran out of fuel as it attempted a soft landing on the moon Tuesday, causing an abrupt end to its five-month journey from launch pad to the lunar surface.

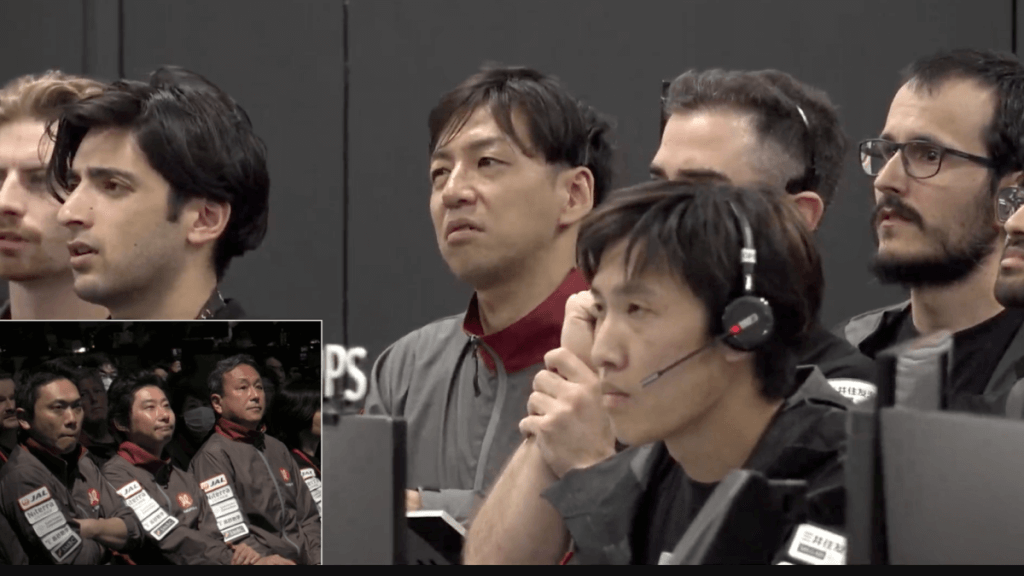

As the lander descended, mission control had communication with it. But after the maneuvers were complete, the team lost contact. About a half-hour after the event, with a room full of visibly disappointed engineers, ispace CEO Takeshi Hakamada said they had to assume the landing was unsuccessful, but they would continue to investigate the status of the lander.

UPDATE: Apr. 27, 2023, 9:37 a.m. EDT Ispace lost contact with the spacecraft immediately after its scheduled landing. Hours after the event, company officials confirmed that a review of data indicated their lander must have crashed.

Following a review of the flight data, ispace says the data points to a “hard landing” — aeronautics-speak for a crash. During its final approach, the lander was vertical, but the team found the lander had consumed all of its fuel prior to touching down. The fuel is needed to fire thrusters to slow during descent. While on empty, the lander’s speed increased as it traveled toward the surface.

The company, ispace, invited the world to watch alongside its Tokyo-based mission control through a livestream of the nail-biting space event on April 25. The landing sequence lasted about an hour as the robotic spacecraft performed a braking engine burn and followed automated commands to adjust the Hakuto-R lander’s orientation and speed to touch down.

Ispace officials said they’re proud of what the mission achieved and that the flight data during the landing phase will help them prepare for their next two lunar missions.

Though 60 years have passed since the first uncrewed moon landings, it remains a daunting task, with less than half of missions succeeding. Unlike on Earth, the moon’s atmosphere is very thin, providing virtually no drag to slow a spacecraft down as it approaches the ground. Moreover, there is no GPS system on the moon to help guide a craft to its landing spot. Engineers have to compensate for these shortcomings from 239,000 miles away.

“We cannot emulate all the environment of the moon on the Earth before the mission,” Hakamada told Mashable in an interview after the event. “So we have to rely on all the simulations and then a lot of assumptions.”

Credit: ispace / YouTube screenshot

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

This is not the first time the private sector has attempted to get to the moon. For example, in 2019 an Israeli nonprofit and company collaborated on the $100 million Beresheet mission, which crashed on the lunar surface after an orientation component failed. The mishap potentially scattered some intriguing artifacts on the lunar surface in the process.

For one of ispace’s payload customers, the failed landing means an indefinite postponement of another dream: the first Arab moon mission. The ispace lander was supposed to deliver the United Arab Emirates’ Rashid rover(opens in a new tab) to the moon, which would explore the Atlas Crater. Along with the Emirati rover, a Japanese space program robot was on board.

Hamdan bin Mohammed, the crown prince of Dubai, said in Arabic on Twitter that the space program would be working on a new rover for a new attempt to reach the moon.

“We have had the honor of trying to reach a new point in the history of the UAE,” he said, according to a Google translation of the statement, “and we have the honor of raising our ambitions so that space, its planets and its stars will be its ceiling.”

Hakuto-R was the first of many other commercial missions expected to attempt this feat soon, many of which are an outgrowth of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services Program(opens in a new tab). The program was established in 2018 to recruit the private sector to help deliver cargo to the moon. Ispace couldn’t directly participate in the NASA program because it isn’t an American company, but it is collaborating on one of the contracts led by Draper Technologies in Massachusetts, expected to land on the moon in 2025.

These upcoming missions will support the U.S. space agency’s lunar ambitions, shipping supplies and experiments to the surface ahead of astronauts’ arrival in 2025 or later. They’re also supposed to kickstart a future cislunar economy, referring to the business potential of ventures on and around the moon.

Credit: ispace

“The environment has changed since I established this company 13 years ago,” Hakamada said. “This is a great market opportunity for a company like us.”

The executive said he wasn’t deterred by the uncertain outcome of the company’s first attempted landing. The data will help the business prepare for its next two upcoming missions, he said.

And he had no regrets about allowing the general public to watch the attempt in real time.

“We tried to be transparent to the world. That will, we believe, (help us) gain more trust in our business and technology,” Hakamada said. “Many people will be given the impression that this is real, and this will pave the way for the greater development of the cislunar ecosystem.”

Which will be the first to make the journey intact? The commercial race is on, with many more opportunities approaching.

“History can be made only by those who (face) challenges, and challenges will not be possible without taking a risk,” said Yuichi Tsuda, a professor of astronautical science at Tokyo University, during the live broadcast. “The risk can be taken only by those who dream. So ispace teams, you are all excellent dreamers.”

This story was originally published on Tuesday, April 25, 2023. It has been updated to include the status report on the lander and an interview with CEO Takeshi Hakamada, along with other reactions.