Two European cubesats have communicated that they are a-ok as they hurtle toward a binary asteroid system to check out the damage inflicted by NASA’s DART impactor in 2022.

DART, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, proved to be an unqualified success when it slammed into the 560-foot-wide (170 meters) asteroid Dimorphos, altering its orbit around the larger space rock Didymos and proving for the first time that humans have the ability to nudge potentially hazardous asteroids out of the way.

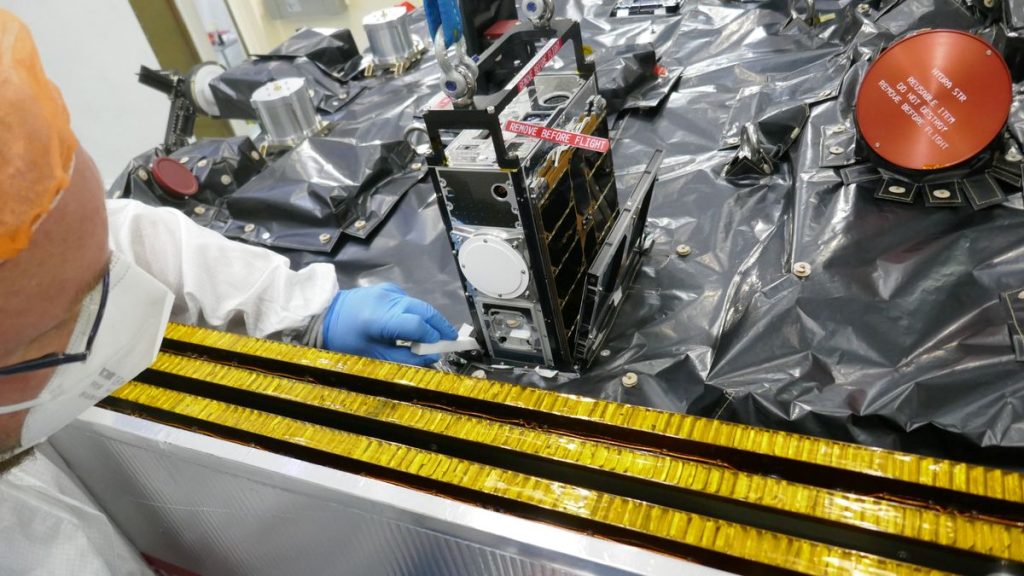

Now, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Hera mission, which launched on Oct. 7, is on its way to check out the damage and learn more about the Didymos-Dimorphos system. Riding with Hera are two small cubesats, named Juventas and Milani. The shoebox-sized craft are stashed inside little “garages” on board Hera called Deep Space Deployers, and they will be released in late 2026 when Hera arrives at the binary system.

First, though, European scientists had to check that Juventas and Milani survived the rock and roll of launch.

Related: Behold the 1st images of DART’s wild asteroid crash!

“Each cubesat was activated for about an hour in turn, in live sessions with the ground to perform commissioning — what we call ‘Are you alive?’ and ‘stowed checkout’ tests,” said Franco Perez Lissi, ESA’s Hera cubesats engineer, in a statement.

Juventas, which will perform a radar study of the interior of Dimorphos, was switched on via radio command on Oct. 17, when Hera was 2.5 million miles (4 million kilometers) from Earth. Milani, which will prospect for minerals on the asteroid’s surface to help determine its composition, was activated on Oct. 24, by which time Hera was 4.9 million miles (7.9 million km) distant and receding farther every minute.

“We were able to activate every on-board system in turn, including their platform avionics, instruments and the inter-satellite links they will use to talk to Hera, as well as spinning up and down their reaction wheels, which will be employed for attitude control,” said Lissi.

Everything was found to be perfectly fine with the two cubesats, and the plan is to switch the cubesats on every two months during their journey to ensure that they remain healthy.

The reason they are tagging along with Hera is that they’ll take greater risks to get closer to Dimorphos than Hera can. Should one of them strike a piece of debris still lingering from the DART impact, or crash into the surface by misjudging the gravitational environment of the Didymos-Dimorphos system, then it won’t be the end of the world. Were Hera to suffer an accident through taking too many risks, it would spell the end of the mission. Hence the need for the cubesats.

Juventas was built and provided for the Hera mission by a Luxembourg company called GOMspace, while Milani is the product of the Italian company Tyvak International. Both companies will remain involved in the operation of the two cubesats while they are exploring Dimorphos.

“During this cubesat commissioning, we have not only confirmed the cubesat instruments and systems work as planned, but also validated the entire ground command infrastructure,” said Sylvain Lodiot, who is the Hera Operations Manager.

Data from the two cubesats is received by the Hera Missions Operations Centre at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Germany, and at the Cubesat Mission Operation Centre (CMOC) at the European Space Security and Education Centre in Redu, Belgium. The telemetry is then passed to the mission control centers at GOMspace and Tyvak International, where scientists will study it in real time and relay any commands back through this chain.

“Verification of this arrangement is good preparation for the free-flying operational phase once Hera reaches Dimorphos,” said Lodiot.

Hera, Juventas and Milani are not voyaging to Didymos and Dimorphos just to gawk at the damage wrought by DART. They’ll also perform the first ever detailed scientific study of a binary asteroid system. Since as many as 15% of all known asteroids are binaries, it makes sense to learn all that we can about them — how they form, what they are made from and how dangerous they might be to Earth.