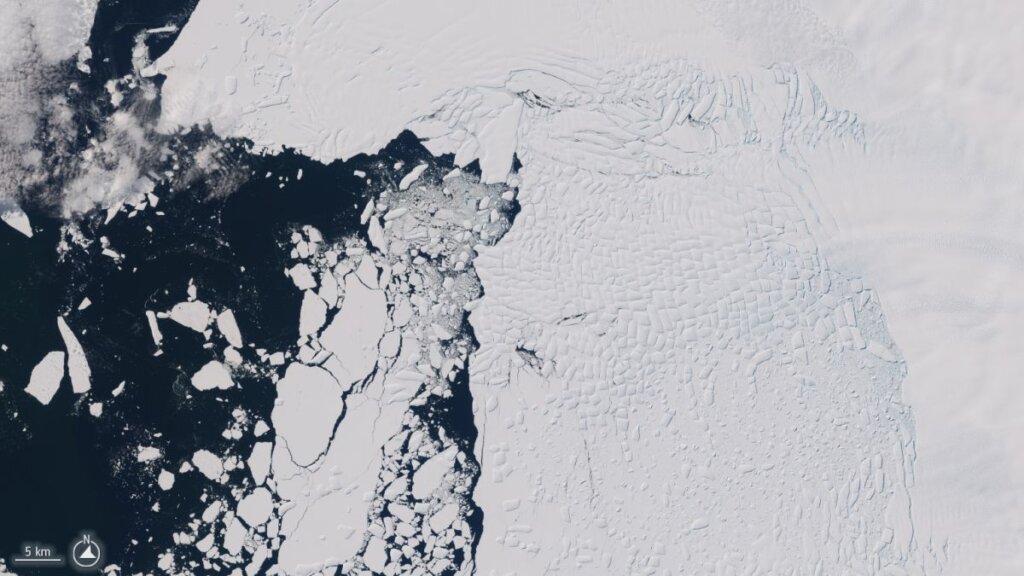

Antarctica may be in serious trouble. Satellite images show that the amount of sea ice floating around the pristine polar continent remains far below long-term averages despite the south polar region moving into its peak winter period.

Researchers at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) observed with trepidation in late 2022 and early 2023 as satellite images revealed that sea ice attached to the coast of Antarctica had been disappearing month after month at a pace never seen before. And they continued to observe in near horror as this sea ice failed to sufficiently replenish after the colder months arrived. As of mid-June 2023, sea ice extent in Antarctica was about 0.9 million square miles (2.28 million square kilometers) below the average from 1981 to 2010 for that part of the year, according to the U.K. weather authority Met Office, and about 0.4 million square miles (1.15 million square km) below the previous June record low from 2019.

Related: 10 devastating signs of climate change satellites can see from space

This development is a worrying deviation from a previous trend that saw Antarctica hold quite steady against progressing climate change, which has long been decimating its northern counterpart, the Arctic. Scientists now worry that the frozen southernmost continent, which plays a crucial role in stabilizing the global climate, may be reaching its tipping point, a point of no return beyond which the polar ecosystem as we know it won’t be able to survive.

“In the Arctic, we have seen a steady decline [of sea ice] over time,” Peter Fretwell, a remote-sensing scientist at the BAS, told Space.com. “Antarctica, up until 2016, was steady, even getting more sea ice, which we couldn’t understand. But since 2016, it’s gone down, and it’s going down even more at the moment. Something has happened, and it’s gone down suddenly very much.”

The amount of floating ice surrounding the polar continent dropped to an all-time low in late February this year, shrinking to 691,000 square miles (1.79 million square km). That’s 50,000 square miles (130,000 square km) below the previous record low of February 2022, according to NASA, which followed a previous record low from 2021.

The problem is, as Fretwell said, that “what happens to Antarctica doesn’t just stay in Antarctica.” The warming polar seas affect weather patterns all over the world and accelerate the melting of Antarctic glaciers that, in turn, will lead to faster sea level rise around the globe.

“Climate change is affecting the polar regions faster than anywhere else in the world. They’re really at the frontline of climate change,” Fretwell said. “But we know that sea ice drives deep water currents around the world, and it has consequences around the world.”

The three consecutive years of unprecedented sea ice loss also bode ill for many of the continent’s species that are unlikely to survive anywhere else. Fretwell and his team are currently scouring satellite images for evidence of the impacts on populations of animals that are known to rely on sea ice for breeding.

For example, changes in sea ice previously decimated one of the largest colonies of the iconic emperor penguin. That colony lost three generations of chicks after sea ice in the Halley Bay in the Weddell Sea broke up too early in the season in 2016, 2017 and 2018. Emperor penguin chicks huddle on the sea ice while their parents fish for food, as they can’t enter the frigid water before developing their outer feathers. When the sea ice disintegrates underneath the colony, the chicks drown or freeze to death.

The alarming decrease of sea ice is also a bad omen for Antarctica’s glaciers, which would, without the buffer of coastal sea ice, become directly exposed to the warming ocean waters. A flurry of recent studies has explored the condition of the melting Thwaites glacier, a vast frozen river flowing into the Amundsen Sea. Dubbed the Doomsday glacier, Thwaites is one of the most vulnerable ice masses in Antarctica. Currently contributing 4% to the global sea level rise, Thwaites could single-handedly increase global sea levels by 26 inches (65 centimeters) if it were to melt completely, according to estimates.

Previous studies have shown that the Thwaites Ice Shelf, a stable floating mass of ice that protects the continental glacier, may completely collapse by the early 2030s, a process that might accelerate if the current trend of vanishing sea ice continues. But Fretwell thinks that all is not lost yet.

“There is still time to stop this oil tanker of climate change,” Fretwell said. “But there is not much time. We now have decades of warming oceans and warming temperatures wired into the system, so if we stop putting carbon in the atmosphere, the world will still continue to heat for decades to come.”

Humankind’s failure to stop emitting greenhouse gases might result in a new Antarctica, one completely different from the continent that we know today. And researchers have no way of knowing how close to this new world we have come.

“With tipping points, you never know whether you’ve come past one,” Fretwell said. Sea ice levels “might come back, but right now, we are in a horrible state of wondering whether it’s going to come back or continue on this track.”