A new AI program can train neural networks using just a handful of images to rapidly characterize in satellite and drone data new objects such as ocean debris, deforestation zones, urban areas and more.

Images taken by drones and satellites give scientists a wealth of information. These snapshots provide crucial insight into the changes taking place on the Earth’s surface, such as in animal populations, vegetation, debris floating on the ocean surface and glacier coverage.

In addition, experts can train neural networks to sort through the images at dizzying speed and spot and classify individual objects. “However, none of the AI programs currently available can immediately switch from recognizing one type of object to another—like from debris to a tree or building,” says Prof. Devis Tuia, the head of EPFL’s Environmental Computational Science and Earth Observation Laboratory.

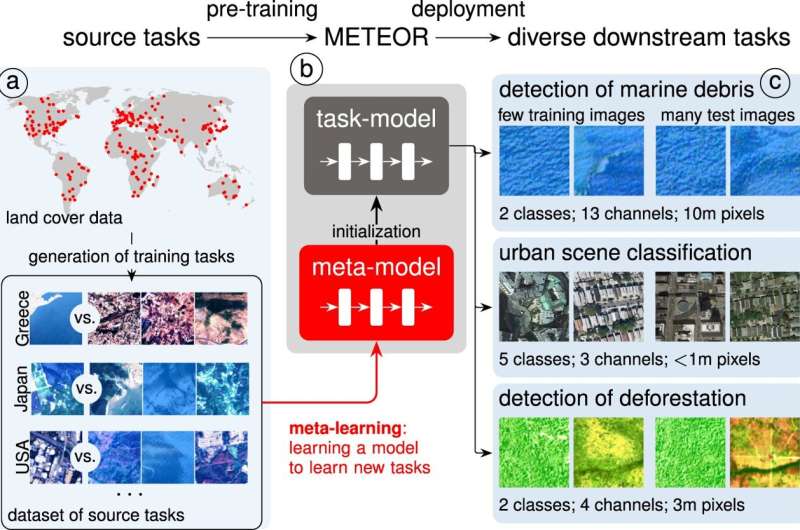

“Today programmers have to train algorithms on each new object type by feeding it vast amounts of field data.” That’s what Tuia and his colleagues, together with scientists from Wageningen University (NL), MIT, Yale and the Jülich Research Center (D), have set out to change with METEOR—a chameleon application that can train algorithms to recognize new objects after being shown just a handful of images.

Their study is published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

When it comes to classifying images, neural networks can do in the blink of an eye what humans would need hours to accomplish. These networks are trained on data that have been annotated manually—the more data fed into a neural network, the more accurate its results will be. For instance, trees and buildings can look very different depending on the region they’re found in. That means a neural network‘s algorithms need to be shown many different images of these objects taken under many different conditions to be able to recognize them reliably.

“The problem in environmental science is that it’s often impossible to obtain a big enough dataset to train AI programs for our research needs,” says Marc Rußwurm, previously a postdoc at EPFL and today an assistant professor at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. “That’s especially true if we want to study phenomena specific to a given region, like the extinction of an indigenous tree species, or if we want to identify objects that are statistically small in number but widely dispersed, like ocean debris.”

Another challenge in training neural networks on aerial and satellite images relates to the wide range of image resolutions and spectral bands possible, and to the type of device used (i.e., from drones and satellites). To get around this problem, METEOR was designed to be adaptable and capable of meta-learning—it essentially takes shortcuts based on tasks successfully solved previously, but in other contexts.

“We’ve developed algorithms and methods that enable neural networks to generalize the results of earlier deployments and apply that adaptation strategy to new situations,” says Rußwurm. Thanks to their novel approach, METEOR needs only four or five good images of an object to deliver sufficiently reliable results.

To test their application, the developers modified a neural network that had been trained to classify various types of land occupation around the world based on images of distinct regions. They made it able to carry out five recognition tasks—measure vegetation coverage in Australia, identify deforestation zones in Brazil’s tropical forest, pinpoint the changes in Beirut after the 2020 explosion, spot ocean debris, and classify urban areas into different types of land use (industrial districts, commercial districts, and high-density, medium-density and low-density residential districts)—using each time a small number of high-resolution drone images and RGB satellite images depending on the problem.

“We found that for these tasks when we adapt with METEOR using only a small dataset, our results were comparable to those from AI programs that had been trained for longer periods and with much more data,” says Rußwurm.

The researchers will now train the basic AI on a multitude of tasks, so that it can further perfect its chameleon powers. This will enable it to adapt even more easily to countless recognition tasks. Also, they’d like to combine their application with a user interface so that human users can click on high-quality images suggested by the neural-network program.

“Since the program will be shown only a few images, the relevance of those images is really important,” says Rußwurm.

More information:

Marc Rußwurm et al, Meta-learning to address diverse Earth observation problems across resolutions, Communications Earth & Environment (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-023-01146-0

Journal information:

Communications Earth & Environment

Provided by

Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne

Chameleon AI program classifies objects in satellite images faster (2024, January 16)

retrieved 17 January 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-01-chameleon-ai-satellite-images-faster.html

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.