Space medical scientists are pushing for the development of an international database on long-term health effects of spaceflight.

This is essential for protecting the health and performance of current and future crew members of all nationalities, as well as defining the long-term health consequences for retired crew members across the globe. That said, there are thorny legal and privacy challenges ahead.

Given that there are now roughly 120 international retired spaceflight crew members still alive, collecting medical or health data on these crew members has the potential to expand the total sample size for health outcomes in space explorers by 40 percent.

Related: Astronauts’ blood shows signs of DNA mutations due to spaceflight

Radiation: Reaching full expression

Understanding the long-term human health impact of space exploration missions is exceptionally challenging. Why so?

Primarily, relatively few humans have ever been exposed to the space environment.

In addition, understanding long-term health impacts requires tracking health and medical status for years after a crew member completes her/his mission.

This is particularly true for those “chronic/degenerative” risks, such as malignancies secondary to radiation exposure, which may take decades to reach full expression.

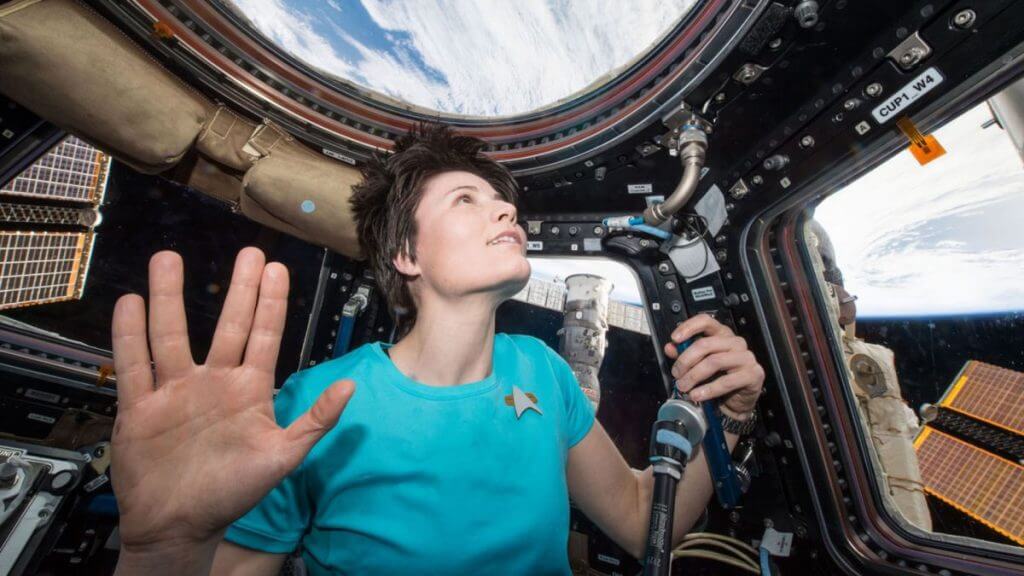

Bottom line: given that the total number of humans who have flown in space is just over 500, and that a growing proportion of International Space Station (ISS) crews are indeed international, it is essential to start capturing medical data from those space travelers.

It is time to develop an international database on long-term health effects of spaceflight. That case has been made in a recent issue of the journal Acta Astronautica.

(opens in new tab)

Data repository

A long-term goal of this database initiative is to establish a secure data repository for biomedical data from international retired crew. Using current technologies, such as, electronic personal health records that enable the individual to collect and transmit her own data, could contribute to more resourceful collection and transmission of biomedical data to such a data repository.

Among the advocate authors of the database idea is former astronaut Bonnie Dunbar. She flew on five space shuttle missions between 1985 and 1998 and is now a professor of aerospace engineering at Texas A&M University College of Engineering.

(opens in new tab)

Feasibility project

“We are exploring funding opportunities to move this project forward,” said Susan Bloomfield, a research professor in health and kinesiology at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas.

“NASA likely cannot fund it since it addresses international (non-American) crew member issues,” Bloomfield told Space.com. “Health technology companies are one option; we already collaborated with one — Care Evolution — during our feasibility project.”

By using retired crew members to gain health data, perhaps that’s a way to avoid medical privacy issues in the “active” astronaut corps?

Bloomfield said that active astronaut corps members in nearly all space agencies have their medical data continuously collected.

Lifetime surveillance

Meanwhile, at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, gathering astronaut medical data was reconfigured in 2010 as an operational program within the space agency and renamed the Lifetime Surveillance of Astronaut Health. Call it LSAH for short.

LSAH within NASA collects data fairly consistently on retired American and Canadian space crew members, Bloomfield said.

“There is no way to avoid medical privacy issues per NASA’s current policies” Bloomfield said. Determined researchers do have way to access those data, but there are many imposed limitations on gathering auxiliary data (e.g., sex, dietary intake, exercise time, pre-existing conditions).

“Our focus on retired crew is to expand the existing data base of medical information on space fliers to better enable future researchers to determine what might be the long-term health consequences of space environment exposure, by extending data collection for decades and by increasing the total ‘n’ [sample size] by at least 40%, as more and more fliers are international,” Bloomfield said.

(opens in new tab)

Streamline data collection

The goal in testing the utility of a personal health record applicant was to streamline the data collection process, by collecting data directly from retired crew members and removing the “middle man” of physician/hospital records administrators, said Bloomfield.

Given the growth of private space travel, to what extent could they help contribute to such a database?

Bloomfield said that the Translational Research Institute for Space Health (TRISH), funded by a NASA Cooperative Agreement and based at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, has already established a medical/health database for commercial fliers’ in-flight data.

“It is not clear, however, that they will track those individuals long-term,” Bloomfield said. “And, frankly, long-term medical issues are far less likely to develop with the hours-to-days duration of those commercial flights (to date).”

(opens in new tab)

Routine autopsies

In their recent paper in the journal Icarus, Bloomfield and colleagues noted:

“Enabling our research scientists to work with a more complete database is essential for protecting the health and performance of our current and future crew members, as well as defining the expected long-term health consequences for our retired crew members across the globe.”

Also, turn your medical eye beyond low Earth orbit.

Given the small number of humans who have been exposed to the Moon’s dust-laden environment, with more to “reboot” the lunar surface, it is essential to proactively promote routine autopsies for those moonwalkers to gain more accurate data defining whether exposure to the lunar space environment increases morbidity or mortality.

For example, the Icarus paper notes, might there be any pulmonary consequences of lunar dust exposure for crew spending time on the lunar surface? Or, is there any correlation between greater exposure to space radiation during moon-bound missions or with multiple spacewalks and earlier/more severe carcinogenesis?”

“Our working hypothesis was that enabling retired crew to manage their own medical/health care data using a convenient application on their own device would result in a more efficient delivery of such data to a central data repository and, importantly, minimize barriers due to international legal restrictions regarding transmission of medical/health data,” the Icarus research paper concludes.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).