Astronomers have witnessed the largest explosion in space.

The explosive event labeled AT2021lwx was observed to be ten times brighter than any known supernova, the explosions that occur as massive stars die. And whereas supernova explosions only last a few months, this explosive event has been raging for at least three years.

AT2021lwx is also three times brighter than the light that is emitted as stars are ripped apart and devoured by supermassive black holes, occurrences called “tidal disruption events” or “TDEs.” The blast is around 8 billion light-years from Earth and thus occurred when the universe was just 6 billion years old.

AT2021lwx was first spotted by the Zwicky Transient Facility in California in 2020 and was then picked up by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) based in Hawaii. Both of these systems are designed to survey the night sky for astronomical events that rapidly change in brightness over time, also known as “transients.” This change in brightness can indicate a supernova or a gamma-ray burst (GRB) deep in the universe or something much closer to home like a comet or an asteroid.

Though it was spotted by these facilities three years ago, the sheer scale and power of the explosion AT2021lwx were unknown until now.

Related: What is a supernova?

“We came upon this by chance, as it was flagged by our search algorithm when we were searching for a type of supernova,” University of Southampton research fellow Philip Wiseman, who led the research, said in an emailed statement. “Most supernovae and TDEs only last for a couple of months before fading away. For something to be bright for two plus years was immediately very unusual.”

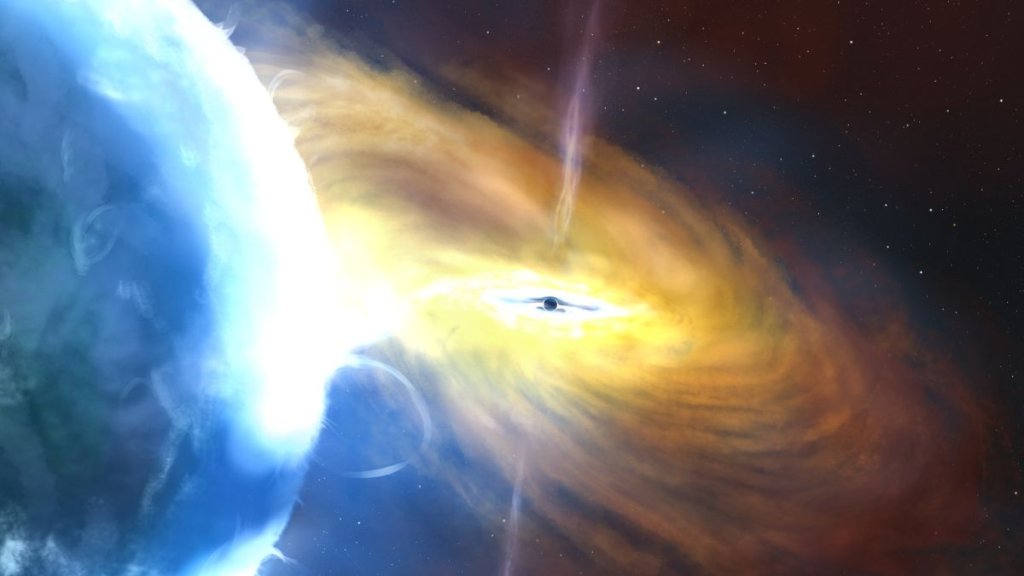

Wiseman and the team of astronomers think that AT2021lwx may be the result of a black hole violently disrupting a cloud of gas with a mass thousands of times greater than the sun. As it did so, the black hole swallowed fragments of the gas cloud, sending shockwaves into both what remains of the gas and into a wider donut-shaped torus of dust surrounding it, causing them to emit bright electromagnetic radiation.

Events like this have been witnessed before, they are rare. What’s more, none that have been witnessed previously have been on the scale of AT2021lwx.

While AT2021lwx isn’t actually as bright as the gamma-ray burst GRB 221009A spotted by astronomers in 2022, this event that erupted from 2.4 billion light-years away lasted for just ten hours after detection. Even though that is quite long for a GRB, it means that AT2021lwx has put out far more energy over its entire lifetime than this gamma-ray burst did in its own.

Measuring the power of a cosmic explosion

Following its initial discovery, the team of researchers behind this discovery continued to examine AT2021lwx using several different telescopes including the Neil Gehrels Swift Telescope, the New Technology Telescope in Chile, and the Gran Telescopio Canarias in La Palma, Spain.

Following these observations, the researchers took the spectrum of light that was emitted from the event and split it down into its constituent wavelengths, measuring how light was emitted and absorbed around the event. This allowed the researchers to calculate the distance to the source of AT2021lwx.

“Once you know the distance to the object and how bright it appears to us, you can calculate the brightness of the object at its source,” team member and University of Southampton professor Sebastian Hönig said in the statement. “Once we’d performed those calculations, we realized this is extremely bright.”

The only thing in the known universe that is as bright as AT2021lwx are supermassive black holes. When these black holes feed on stellar gases that fall into them at high velocities, they can let off incredibly bright emissions known as quasars.

“With a quasar, we see the brightness flickering up and down over time,” team member and University of Southampton professor Mark Sullivan added. “But looking back over a decade there was no detection of AT2021lwx, then suddenly it appears with the brightness of the brightest things in the universe, which is unprecedented.”

Though there are other possible explanations for the explosive event, the astronomers currently favor the explanation that sees an extremely large cloud of mostly gaseous hydrogen or dust that was knocked from its orbit around the black hole and sucked into it. This will only be conclusively determined when the team has collected more data about AT2021lwx.

The team will now look at the explosion in different wavelengths of light including X-rays. Doing so could reveal the temperature of the event and what processes are driving it. They will also conduct computer simulations to discover if their model of a titanic gas cloud disrupted by a black hole could account for AT2021lwx.

“With new facilities, like the Vera Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time, coming online in the next few years, we are hoping to discover more events like this and learn more about them,” Wiseman concluded in the statement. “It could be that these events, although extremely rare, are so energetic that they are key processes to how the centers of galaxies change over time.”

The team’s research is discussed in a paper (opens in new tab) published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.