Astronomers have discovered a rare temperature-sensitive molecule that is usually associated with stars in the atmosphere of an exoplanet for the first time.

The “thermometer molecule” chromium hydride is abundant in a narrow range of temperatures between 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit to 3,140 degrees Fahrenheit (926 to 1,730 degrees Celsius). It was discovered in the atmosphere of the “hot Jupiter” exoplanet WASP-17b, which orbits an F-type star located around 1,250 light-years from Earth.

The discovery of such a metal hydride — a metal bonded to hydrogen to form a new compound — in the atmosphere of an alien planet could allow scientists to gauge the temperatures of worlds outside the solar system in a new way.

“Chromium hydride molecules are very temperature sensitive,” research lead author Laura Flagg, a research associate at Cornell University in New York, said in a statement. “At hotter temperatures, you see just chromium alone. And at lower temperatures, it turns into other things. So there’s only a specific temperature range where chromium hydride is seen in large abundances.”

Related: 10 amazing exoplanet discoveries

Toasting a cosmic marshmellow

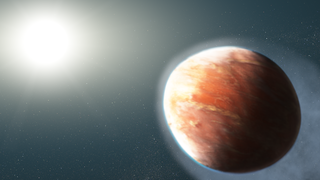

Discovered in 2010, WASP-17b was already known to be a pretty extraordinary and extreme exoplanet before the team found chromium hydride in its atmosphere. The hot Jupiter is located just 4.3 million miles (6.9 million kilometers) from its parent star, so close that it completes an orbit in just 3.4 Earth days.

This proximity to the host star, called WASP-17, causes extreme temperatures on the hot Jupiter of around 2,060 degrees Fahrenheit (1,130 degrees Celsius), as confirmed by Flagg and her team. That temperature is just right to host chromium hydride molecules.

The extreme temperature of WASP -17b has another consequence: causing the atmosphere of the gas giant to “puff out.”

This means that, despite having a mass less than half that of Jupiter, Wasp-17b is more than 1.5 times wider than our solar system’s largest planet. That gives Wasp-17b a density around 13% that of Jupiter, or around 0.17 grams per cubic centimeter.

By comparison, a marshmallow has a density of 0.21 grams per cubic centimeter. So WASP-17b, one of the lightest exoplanets ever discovered, is actually less dense than a marshmallow.

Hunting for a chromium fingerprint

The team of astronomers spotted chromium hydride in the atmosphere of WASP-17b while using high-resolution spectroscopy. Elements and chemical compounds absorb light at specific wavelengths, leaving their characteristic fingerprints in the spectra of light coming from a star, which can be assessed with spectroscopy.

Flagg and her colleagues compared the spectra of light coming from a star when its orbiting planets were at its side to spectra coming from the star when the planet transits, or crosses, its face. In this second case, the light from the star has to traverse through the atmosphere of the transiting planet, and thus, the team can spot the fingerprints that weren’t present in the spectra of light collected from the star alone. This tells the team which of these elements and compounds exist in the planet’s atmosphere.

“High spectral resolution means we have very precise wavelength information,” Flagg said. “We can get thousands of different lines. We combine them using various statistical methods, using a template — an approximate idea of what the spectrum looks like — and we compare it to the data, and we match it up. If it matches well, there’s a signal.

“We try all the different templates, and in this case, the chromium hydride template produced a signal.”

Chromium is rare, even at the “correct” temperatures, meaning that Flagg and colleagues needed highly sensitive data to confirm its presence. This came in the form of observations of WASP-17b and its star made by the GRACES instrument (short for “Gemini Remote Access to CFHT ESPaDOnS Spectrograph”) at Hawaii‘s Maunakea observatory in March 2022. The team bolstered the GRACES data using data collected in 2017, which was not intended to hunt for metal hydrides.

“Part of our data for this paper was old data that was on the very edge of the data set,” Flagg continued. “You wouldn’t have looked for it.”

She now intends to hunt for metal hydrides in the atmospheres of other exoplanets, suspecting that this evidence may have already been collected but could have been missed thus far.

“I’m hoping that this paper will encourage other researchers to look in their data for chromium hydride and other metal hydrides,” Flagg said. “We think it should be there. Hopefully, we’ll get more data that will be suitable for looking for chromium hydride and eventually build up a sample size to look for trends.”

The team’s research was published this month in the The Astrophysical Journal Letters.