A lightweight version of the International Space Station’s robotic arm will help space sustainability company Astroscale remove decades-old space junk from Earth’s orbit in the first mission of its kind.

Astroscale, which has offices in Japan and the U.K., previously ran a demonstration of active space debris removal technology with its ELSA-d mission, which in 2021 successfully captured a piece of simulated debris using a magnetic system. That technology requires the target satellite to be equipped with a magnetic docking plate from the get go and so could only be used on satellites developed with debris removal in mind, like those launched by internet megaconstellation operator OneWeb, which is Astroscale’s partner in the follow-up mission ELSA-M.

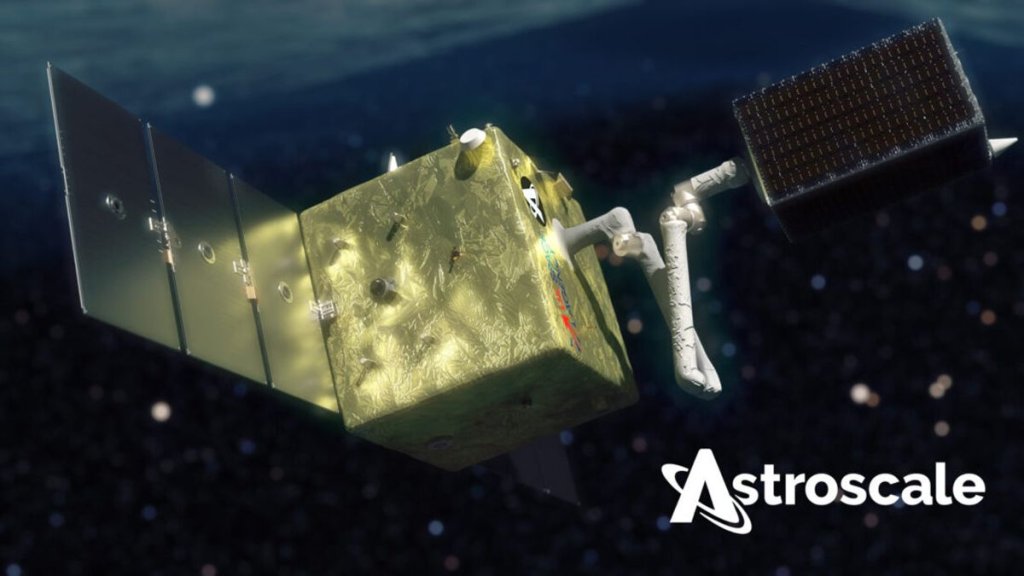

But the new technology, developed for a U.K.-funded mission called Cosmic (for Cleaning Outer Space Mission through Innovative Capture), intends to take active space debris removal to another level by targeting old satellites that have been tumbling in space for decades and have no special features for a removal spacecraft to attach to.

Related: 6 types of objects that could cause space debris apocalypse

“The function of this mission is to remove two pieces of U.K.-owned defunct debris satellites that are presently up there,” Jason Foreshaw, Astroscale’s head of future business, told Space.com. “There are some satellites which were launched in the 1990s that have really come to the end of life, and a lot of those are kind of in the region under 100 kilograms [220 pounds]. And so our aim is to actually launch this mission to remove two of these failed satellites that are at altitudes of roughly 500 to 800 kilometers [310 to 490 miles].”

The Cosmic debris removal spacecraft is likely going to face many more challenges than ELSA-M, the collaboration with OneWeb. The long-defunct satellites Cosmic will target may have partially disintegrated in the harsh environment of space, with pieces falling off that might make them difficult to grab. Long-dead spacecraft are also likely to tumble as they hurtle through the vacuum of space at speeds of over 15,000 mph (24,000 kph), making the capture even trickier.

“Capturing a dead satellite that’s been in space for 30 years is very, very challenging,” said Foreshaw. “We don’t know the condition of the satellite. Is it structurally intact? Have parts fallen off? Has it been hit by debris? Space is a very harsh environment. So we don’t know the condition until we get there and we do an inspection to find out exactly what it looks like. Does it look the same as it did when it was launched 30 years ago? I think those are some of the real challenges.”

Astroscale thinks that it can tackle the challenge using the autonomous navigation software tested by ELSA-d, and a cutting-edge robotic arm currently developed by MDA, the same company that built the International Space Station‘s robotic Canadarm2 in the 1990s.

Foreshaw said the robotic arm would grab the old satellite by its launch adapter ring, a circular structure used to mount the payload to the rocket. The junk collector craft would then drag the debris into a very low orbit, from where it would speedily enter Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. The debris removal spacecraft would then return to collect a second object.

The mission is currently in consideration for funding from the U.K. Space Agency, which will decide between Astroscale and a competing cleanup proposal by Switzerland-headquartered CleanSpace.

If selected, the mission would launch in 2026, about a year after ELSA-M. Through ELSA-M, Astroscale hopes to further mature its technologies, especially the autonomous approach and navigation system, before attempting the more challenging old-junk capture.

Space debris is a growing problem. Some 34,260 debris objects — including used rocket stages, old satellites and fragments created in collisions — are currently tracked by space surveillance networks, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). This number is bound to grow in the coming years as more and more satellites are being launched, a trend driven by the developers of satellite megaconstellations such as the one operated by OneWeb and SpaceX‘s gigantic Starlink network.

Scientists worry that the amount of out-of-control objects hurtling around the planet could lead to devastating, fragment-producing orbital collisions. Apart from putting operational satellites at risk, these collisions could in the longer term make the orbital environment around Earth too dangerous for satellites to operate, as every orbital collision would generate so many fragments that further collisions would ensue. This cascade of collisions, known as the Kessler Syndrome, was first theorized by former NASA scientist Donald Kessler in the late 1970s. Some scientists think that the early stages of this disconcerting phenomenon may already be underway. Active debris removal is seen as a key technology to keep space usable in the decades to come.

Astroscale also has plans to inspect and later remove a discarded Japanese rocket stage using a spacecraft built in cooperation with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). That spacecraft, called ADRAS-J, could embark on its space-cleaning mission in 2025, according to Astroscale. ESA also plans to remove a spent rocket body from orbit in 2025 using a junk collector spacecraft built by Astroscale’s competitor ClearSpace.

Astroscale detailed the plans for its Cosmic mission in a new video unveiled exclusively on Space.com.