The Uranian moon Miranda may contain a liquid water ocean, according to a team of researchers that recently mapped the satellite’s surface and modeled tidal stress on it.

The team published its study earlier this month in The Planetary Science Journal, suggesting the “plausible existence” of an ocean at least 100 kilometers (62 miles) thick on Miranda within the past 100 to 500 million years. Though the researchers don’t think such a deep water body is still present, liquid water may remain under the moon’s surface, as one researcher told the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. If Miranda had frozen completely, the team believes there would be certain cracks on the moon’s surface—evidence of the frozen ocean’s expansion within. No such cracks are present, based on the researchers’ review of the available imagery.

“To find evidence of an ocean inside a small object like Miranda is incredibly surprising,” said Tom Nordheim, a planetary scientist at the laboratory and co-author of the recent paper, in a lab release. “It helps build on the story that some of these moons at Uranus may be really interesting—that there may be several ocean worlds around one of the most distant planets in our solar system, which is both exciting and bizarre,” Nordheim added.

The seventh planet from the Sun is often the butt of people’s jokes, but it remains an exciting venue for planetary scientists. In 2022, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine made the probing of Uranus a top priority for the decade. And rightly so: Uranus is an oddball among worlds, with an odd tilt, a big white splotch, extreme seasons, and infrared aurora in its gassy atmosphere. Though we often think of Saturn as the ringed planet in our solar system, Webb Space Telescope images published last year revealed luminous rings around Uranus in more brilliant detail than ever before.

And that’s to say nothing of Uranus’ moons, of which there are nearly 30. Earlier this year, a different team of astronomers discovered a new moon orbiting the planet, the first to be found in over 20 years. That moon is only five miles (eight kilometers) wide, and has a nearly two-year orbit around the planet. Though not yet named, that moon will eventually get a Shakespearean name like its rocky brethren surrounding Uranus (besides Miranda, there are Rosalind, Puck, Belinda, Desdemona, Cressida, Juliet…I could go on).

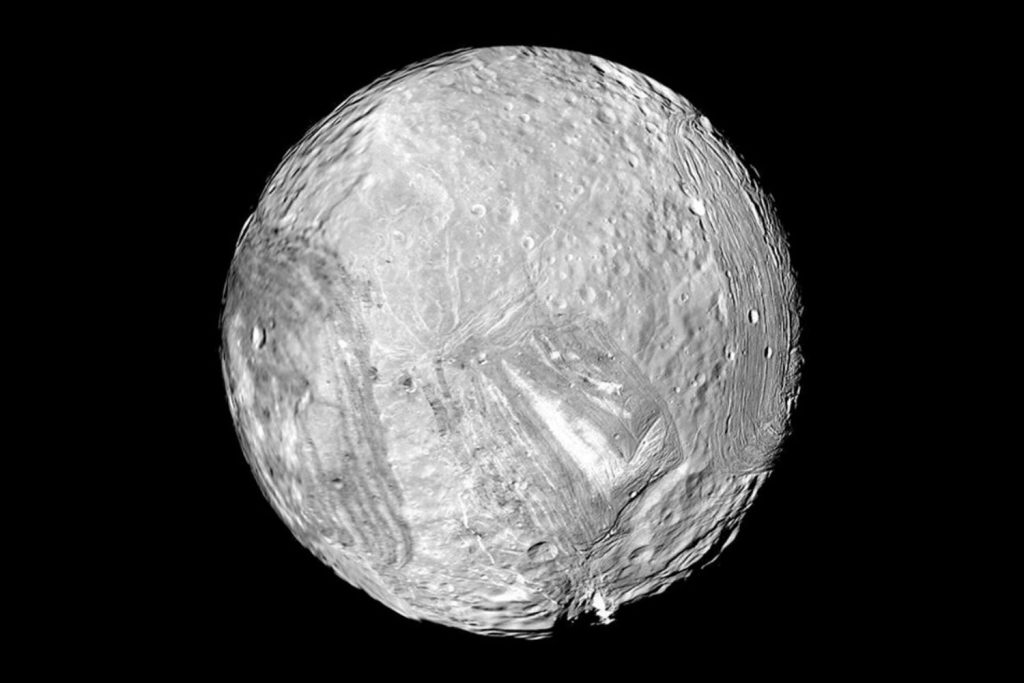

But this story is about Miranda. In the top image you can see one of the few up-close images we have of the icy moon, snapped by NASA’s Voyager 2 in 1986, as the intrepid spacecraft made its way out of our solar system. The image shows the gnarly surface of Miranda—covered in grooves and craters that scientists believe are due to tidal forces on the moon and heating within it.

In the recent study, the team modeled the moon’s interior based on the features of its exterior; essentially, the team analyzed evidence of stress and shear on Miranda’s surface to infer the internal forces that may have shaped the moon’s appearance. In the paper, the team wrote that orbital changes due to gravitational interaction between Miranda and other Uranian satellites may have generated a pulse of heat within the moon, creating a deep ocean at some point in the ancient past.

The team also wrote that an approximately 8-mile-thick (30-kilometer-thick) crust “would also imply” a 62-mile-thick (100 km-thick) “subsurface liquid water ocean.” For reference, the Mariana Trench—the deepest point in our world’s’ oceans—is just 6.83 miles deep (11 km). While such a deep ocean likely no longer exists, the idea that it was once there—and the fact that a thin ocean may persist—holds water.

“Such a thick ocean may have made Miranda very Enceladus-like,” the team explained, “and potentially habitable, in the geologically recent past.”

Astrobiology—the search for life beyond our planet—is one of the most exciting arenas of space research. It is part and parcel to much of what we do in space, from putting rovers on Mars to imaging distant exoplanets, orbiting their own stars light-years away. Despite some of those far-off targets, some astrobiologists believe that our best bet for life off-Earth is relatively nearby—in the subsurface oceans of icy moons like Europa, Ganymede, Enceladus, and Miranda.

It will be years before any space agency actually gets a probe to Miranda, but some icy discoveries could be around the corner. The JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) and Europa Clipper missions are on their way to the Jovian system now, to reveal Jupiter’s icy moons in greater detail. What they find could provide useful context for better understanding Miranda, whose subsurface may yet yield a brave new world for us to understand.