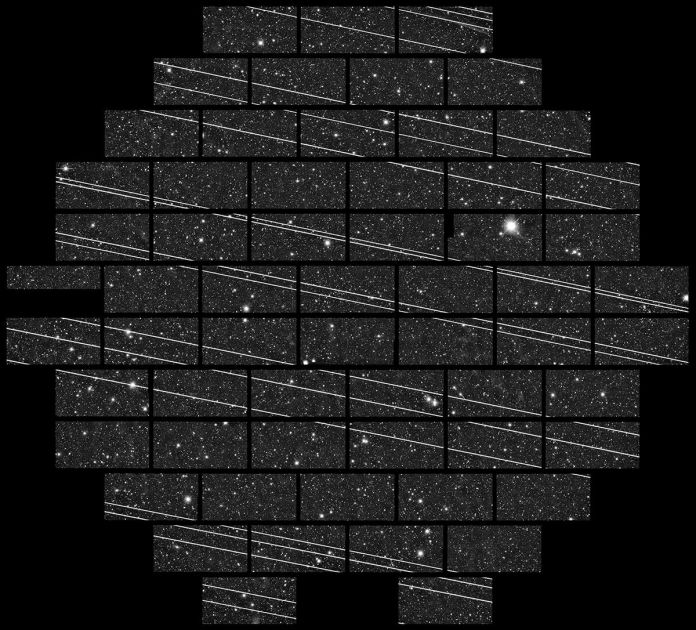

Astronomers are praising SpaceX’s response to months of outcry over the visibility of the company’s Starlink internet satellites from scientists dismayed by interference with observations.

The SpaceX response includes a new strategy for reducing the amount of light Starlink satellites reflect down to Earth. But Starlink is only the first of the so-called megaconstellations that companies plan to develop. These programs aspire to encompass thousands, sometimes even tens of thousands, of satellites in orbit around Earth. SpaceX is the first company to have a fleet of hundreds in orbit, and that vanguard alerted optical astronomers they had a new problem to tackle: a huge increase in satellites reflecting streaks of light at scientific observatories.

“We all knew [the satellites] were coming, but we never imagined they were going to be so bright,” James Lowenthal, an astronomer at Smith College in Massachusetts, said during a plenary talk at the 236th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), held virtually on June 2.

“For one thing, we didn’t know how big the satellites were; that was not public information,” Lowenthal, a member of a working group formed by AAS to address the issue, continued. “And we didn’t know what elevation they were going to be at. The combination has made them much, much brighter than we anticipated — that was the big surprise.”

The problem has been particularly noticeable soon after each Starlink launch, before the satellites reach their final orbital altitude of about 340 miles (550 kilometers), since they can be seen by the unaided eye during this time. But operational satellites continue to interfere with sensitive observatories.

And despite the outcry of astronomers, these satellites aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. Lowenthal said independent estimates value the Starlink program at about $10 billion, on the financial scale of NASA’s massive James Webb Space Telescope.

But he and the other members of the AAS working group have been speaking with SpaceX on a monthly basis. “The focus has been on how SpaceX can dim the satellites and how astronomers can dodge them,” Lowenthal said. “Stopping the launches is not on the table. They already have permission. They don’t need to ask us for any more permission, they’ve already gotten it.”

What the company did ask astronomers for was more detail about how the satellites have interfered with observation schedules and equipment, particularly sensors. Those conversations have led to SpaceX developing three experiments for the Starlink fleet this year.

“We’ve taken an experimental and iterative approach to reducing the brightness of the Starlink satellites,” SpaceX representatives wrote in a statement released in April. “Orbital brightness is an extremely difficult problem to tackle analytically, so we’ve been hard at work on both ground and on-orbit testing.”

The first experiment was a variant satellite called DarkSat that launched in January, with a few particularly reflective surfaces painted black. The intervention made the satellite noticeably fainter, Lowenthal confirmed, but still visible to the unaided eye, much less sophisticated observatories. “That’s good progress, but it’s not going to solve our problems,” he said. But the black paint also retained too much heat, according to SpaceX.

A second experimental satellite launched in the most recent Starlink batch, on June 3, and by the end of the month all Starlink satellites to launch will carry these visors, SpaceX has already said. This design uses visors to block sunlight from reaching the most reflective of the satellite’s surfaces once it reaches its operating altitude.

The company’s statement suggests that those two approaches aren’t necessarily the only changes SpaceX will try on the Starlink fleet moving forward. “SpaceX is committed to making future satellite designs as dark as possible,” the statement reads.

Meanwhile, SpaceX is testing a different solution for managing reflectivity as satellites launch and climb, before the visors can make much of a difference. Because this experiment operates on the computer code running the satellites, rather than on the satellite as an object, the approach can be applied to already-orbiting Starlink satellites as well as future launches.

The technique relies on twisting the satellites during crucial points in their orbits so that the solar panels lie flat and point directly from Earth to the sun, nearly eliminating the proportion of their surface visible from the ground. The company believes that should dramatically reduce the satellites’ brightness, although they will still sometimes be visible.

“There are a couple of nuanced reasons why this is tricky to implement,” company representatives wrote in the statement. “This could result in the occasional set of Starlink satellites in the orbit raise of flight that are temporarily visible for one part of an orbit.”

For Lowenthal, those steps are important. “Bottom line, SpaceX has devoted significant resources to these technical solutions,” he said. But only observations will tell how much the visors and orientation techniques actually reduce the impact of Starlink on astronomy.

And the same two factors that have proved so challenging with Starlink — the satellites’ size and altitude — will shape how all future megaconstellations impact astronomy, Lowenthal said. What is less clear is whether the operators of those constellations will take into consideration astronomers’ concerns about their fleets.

So far, SpaceX is the only company with megaconstellation dreams that has proven to be communicative. Lowenthal said his group met with OneWeb once, before the company’s bankruptcy declaration at the end of March. And that’s it.

“We’ve had no major conversations with other operators,” he told the gathered astronomers. “There’s no guarantee that all of these, or even any of them, will be good citizens, as we would say SpaceX has been.”

– Advertisement –