It took four years of negotations for Canada to get a seat on NASA’s upcoming moon mission.

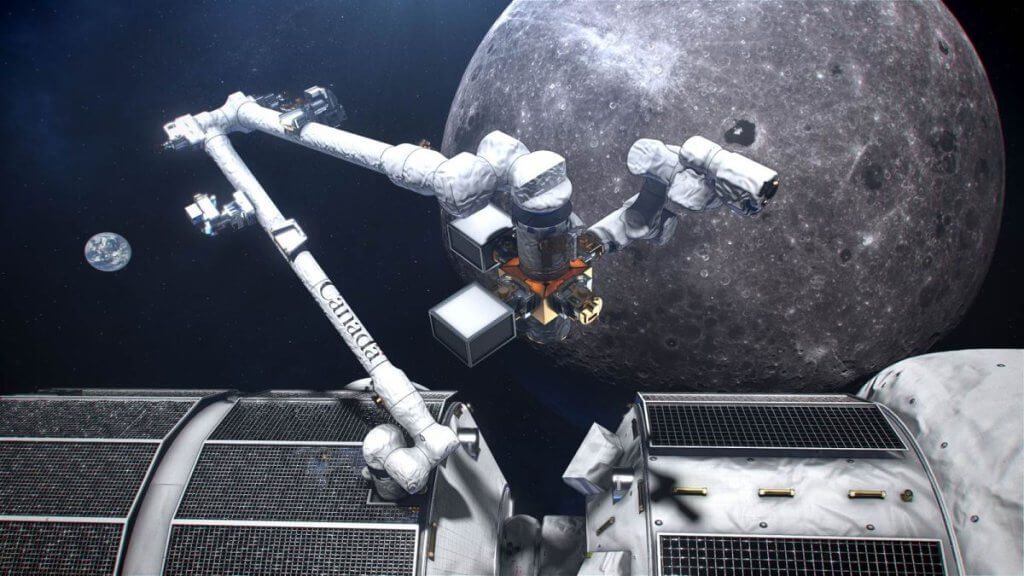

That mission, Artemis 2, will send a Canadian and three Americans around the moon no sooner than November 2024. The Canadian seat comes courtesy of a big contribution to NASA’s Artemis program: Canadarm3, a robotic arm that will service the planned Gateway moon-orbiting space station. (The identities of the Artemis 2 crewmembers are currently unknown but will be revealed on Monday, April 3, in a live NASA event that you can watch here at Space.com.)

Canadarm3 was announced in 2019 as part of a big push in Canadian federal government circles to reprioritize space exploration. The government pledged US $1.56 billion USD in space spending over 24 years ($2.05 billion CAD under 2019 exchange rates). That’s $65 million USD a year, a fairly significant amount for a space agency that specializes in niche projects.

Much of that Canadian Space Agency (CSA) money was for Canadarm3, but some was also earmarked for a business incubator known as the Lunar Exploration Acceleration Program (LEAP). Other support went to food and health tech development contests designed to assist future deep space astronauts.

Getting all that funding and securing a seat on Artemis 2, however, took four years of behind-the-scenes negotiations. To introduce what happened, let’s talk about something that may not sound all that space-y at first: potato salad.

Related: NASA’s Artemis program: Everything you need to know

Canada is a powerful tech specialist that has been supplying highly capable space robotics since 1981 — Canadarm for the space shuttle program; Canadarm2 for the International Space Station (ISS), along with a “handy robot” named Dextre; and Canadarm3, which will be built by the company MDA. These are all crucial tools used for applications such as spacewalking, satellite repairs and space station servicing.

Ken Podwalski, a senior CSA official involved with the Artemis 2 and Gateway negotiations, likens the reputation of Canada’s space robotics to the dinner guest who comes armed with a divine side dish: “People look at Canada and say, ‘Canada, you guys make the best potato salad, bar none. It’s the best potato salad you can get. Nobody does it like you.'”

His confidence comes from decades of space experience. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, for example, would not be running today without Canadarm, which was used on five space shuttle servicing missions to the iconic observatory from 1993 to 2009. Nor would the ISS exist in its current form without Canadarm2, which berths cargo ships, assists in construction and even starred in a spectacular 2007 emergency spacewalk to fix a torn ISS solar panel.

Related: Astronauts ready for solar wing surgery

(opens in new tab)

But in 2015, when the future of the ISS collaboration was being discussed within Canada, the U.S. and other nations, there were lots of questions about what would happen next. Canada was just changing over from a Conservative to a Liberal government for the first time in nearly a decade, following the 2015 election.

The U.S. was on the eve of the 2016 election, which brought in a new presidential administration as well. Numerous ideas were batted about concerning the direction of NASA’s human spaceflight program over the coming years. Would the agency work toward a crewed visit to an asteroid? A moon mission? How quickly and with whom? And within Canada, no space plan for government spending direction had been formulated for many years, making roadmaps similarly uncertain — until a high-level strategy document came out in 2019.

The multinational space groups Canada is a part of all agreed on one thing, Podwalski said: Mars was the ultimate destination. The question simply came down to which pathway to take. The CSA created its own planning group that used the ISS agreements as a starting point. Gateway, though changing design and scope periodically, was a solid enough target to plan discussions with NASA during the 2015 to 2018 negotiations, he said.

“We were going through this quite intensive time. We were doing presentations with the partners and trying to understand what the right fit was,” Podwalski recalled. “We were [also] doing presentations with our government, trying to make sure that we’re taking the right approach.”

Related: Maple leaf to the moon: Canadian Space Agency debuts new logo

(opens in new tab)

Building the new Canadarm3 was established as the primary aim. Podwalski, citing what he calls the “potato salad speech” he brings out in such planning meetings, said he always told people that focus was essential.

“Everybody expects Canada to bring the potato salad,” he said. “The potato salad gets you in the door, no problem … and it doesn’t stop you from bringing anything else. You’re now a part of the party. Now’s a good time to bring up other things.”

He thus urged his collaborators to deprioritize expensive and newer work that Canada could undertake, such as space modules or large rovers. But they also sought other avenues where modest investments could have a powerful impact and involve many smaller companies in related industries to space. Through these conversations, a mini moon rover (announced in 2021), a lunar utility vehicle (announced in the Canadian federal budget on March 28) and the CSA LEAP incubator program (renewed in the 2023 federal budget) all eventually came to be as well.

Canadarm3 was also designed to align with the priorities of the Canadian government. Serving remote communities in the north, especially Indigenous groups, through spinoff medical technology? Check. Continuing to grow Canada’s artificial intelligence community, a key tech direction for the country? Another big check, as Canadarm3 will be autonomously operating without astronaut crews nearby for at least 11 months a year. Preparing for Mars? Absolutely, as the artificial intelligence and robotics will also be beneficial on a more faraway planet, Podwalski said.

Related: Meet Au-Spot, the AI robot dog that’s training to explore caves on Mars

(opens in new tab)

Podwalski emphasized how important it was to stay flexible through the negotiations, which extended through several U.S. election and Canadian cycles across 2015 to 2018, not to mention policy changes in the European Space Agency, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and other partners.

“It is difficult to pull together these multibillion-dollar programs and get all these partners with all their own agendas about what they want to do in space, what technologies they want to develop and what they want to do with their industry,” he said.

Formulations also will continue to change on the key hardware, he emphasized, and negotiations are always undertaken with that flexibility in mind. For example, he said, it’s possible that Gateway may alter again after SpaceX‘s Starship achieves its first spaceflight as soon as this month, given that Starship could carry a considerable amount of cargo to lunar realms.

But for Canada, the benefits from Canadarm3’s “potato salad” approach have been considerable so far. The Artemis 2 seat, when offered by NASA, met the CSA’s goal of having an early moon mission with an astronaut on board to build industry and scientific momentum for other moon ventures, Podwalski said.

So far, NASA has also promised a long-duration Gateway mission to Canada sometime in the future. Other astronaut lunar journeys may come, including a landing mission, in negotiations down the road.

The ISS journey will continue alongside Artemis, too. Canada last month committed to extending its ISS participation to 2030 alongside other partners who agreed to that last year, most crucially NASA. (Russia has said it aims to exit the ISS partnership sometime after 2024.) Canada will also fly an astronaut to the ISS again in 2024 or 2025, the Canadian federal budget confirmed a few days ago.

Podwalski urged the community to keep watching for new announcements. “We’re a partner in good standing,” he said of the ISS and Artemis consortiums. “We’re part of the initial [moon] foray; we’re part of the trailblazers. It really does position Canada in a good way.”

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of “Why Am I Taller (opens in new tab)?” (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).