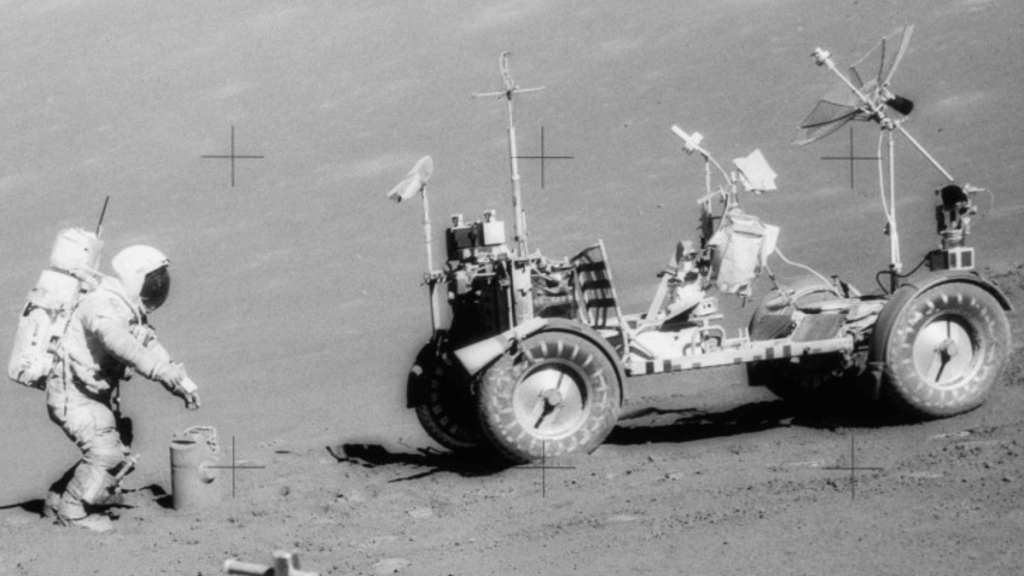

What do we do with the pieces of Apollo moon missions, or other bits of human technology scattered around the solar system?

As NASA and other entities plan to put humans on the moon again later in the 2020s, a new study suggests we should see what changes the lunar environment causes on human artifacts left on the surface, with an eye to preserving what is possible: Spacecraft, experiments, trash and other things.

“The material record that currently exists on the moon is rapidly becoming at risk of being destroyed if proper attention isn’t paid during the new space era,” lead author Justin Holcomb, postdoctoral researcher at the Kansas Geological Survey (based at the University of Kansas), said in a July 21 statement.

This study would also apply to other worlds that humans have visited with spacecraft, such as the Mars rovers, landers and crash-sites that are whipped by dry winds. Many a Red Planet mission there has succumbed to the extreme temperatures or rampant dust, which gets into everything.

Related: The weirdest things Apollo astronauts left on the moon

Archaeology is the study of humans and their artifacts from prehistory to the present, so space archaeology, by extension, is “the study of the material culture associated with space exploration from the twentieth century onwards,” according to the Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Early rocketry experiments now associated with space exploration began in the 1920s, so by that judgement space artifacts are roughly a century old at most.

To be sure, NASA does what it can. Aside from numerous space museums preserving its returned artifacts on Earth, the agency has called for careful exploration of the moon in the past. It carefully documents its activities on other worlds with an eye to the future. Also, NASA and many other international space agencies abide by United Nations treaties that set agreements for how space is explored; this would imply not only respect for people, but for the artifacts that are left by those people.

Australian space archaeologist Alice Gorman is one of the pioneers of space archaeology, and is co-leading a study of the International Space Station‘s artifacts, among many other projects. References in her 2021 peer-reviewed paper about her space station project suggests that the term “space archaeology” became popular around the turn of the millennium. (Possibly the 30th anniversary of the Apollo 11 pioneering human moon-landing mission of 1969, which fell in 1999, had something to do with it.)

Some scientists, however, define “space archaeology” as peering at archaeology from space, using satellites. A prominent example of this is National Geographic explorer Sarah Parcak, an archaeologist and a professor of anthropology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The University of Kansas’ Holcomb, however, refers to “space archaeology” as preserving artifacts of spaceflight.

Related: ‘Space archaeology’ research on the ISS will help design better space habitats

Holcomb and his team suggest creating a new subfield of space archaeology called “planetary geoarchaeology”, referring to how cultural and natural processes of a world (like Earth) influence artifacts upon the surface.

Artifacts like satellites — or spacecraft flying to another world — don’t quite qualify as planetary geoarchaeology sites, as long as they are orbiting in space. But crash sites or landing sites of these machines would likely count. The Union of Concerned Satellites suggests more than 6,700 satellites are orbiting Earth right now, and there are high numbers of other spacecraft currently flying elsewhere in space or residing on other worlds.

NASA plans to return humans to the moon on its Artemis 3 mission no sooner than 2025 or 2026, assuming the program remains on schedule. (Artemis 2, a mission to fly around the moon with humans on board, is set for November 2024 at the moment.) Holcomb said the new Artemis program is renewing the calls to preserve Apollo artifacts on site. That issue once even prompted a bill before U.S. Congress in 2013.

“I do think there’s a risk to this heritage on the moon,” Holcomb said of the new generation of moon explorers. Most countries of the world have signed on to the United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty establishing international norms of lunar exploration, but NASA’s Artemis Accords for moon work and peaceful collaboration in space include only 27 countries. Russia and China are creating their own new space alliance, recently signing Venezuela on board. This doesn’t even mention the number of private companies that can now explore lunar realms independently.

Holcomb would like to see archaeologists involved on the front lines of moon and Mars exploration, especially to preserve key sites like the Apollo 11 landing zone in the Sea of Tranquility, or the pioneering NASA Viking 1 site at Chryse Planitia on Mars.

Aside from continuing to track objects, update laws and monitor the effect of the environment on spacecraft, he urges the community to keep a watchful eye on artifacts at risk. Martian rovers and spacecraft are particularly prone to being buried, he said, putting them out of reach for future scientific study.

The main goal of the paper, the text states, is to “spur more research studying human–environment interaction in space.” It was published June 11 in the peer-reviewed publication Geoarchaeology.