Aurora watchers, it’s your lucky month.

For the second time in days, the sun hurled a large, X-class flare at Earth overnight Tuesday (April 19) and Wednesday (April 20), reportedly causing radio blackouts in Australia, the Western Pacific and eastern Asia. SpaceWeather.com reports 19 flares overall, including five medium-class explosions.

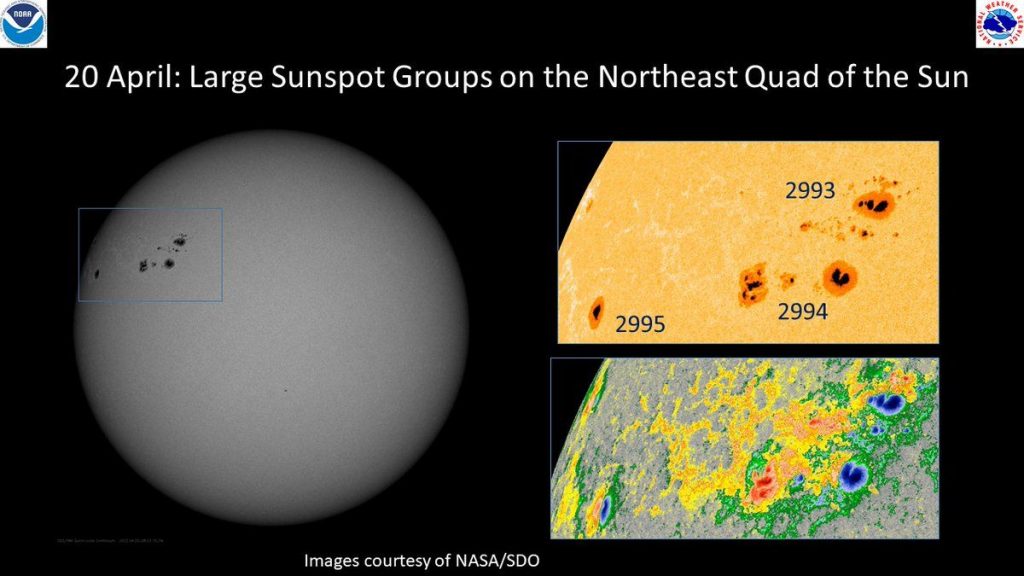

There’s likely more action in store, too. Imagery from NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory shows the large sunspot group AR2993-94, ready to rotate into firing range of Earth. “The fusillade is likely to continue,” SpaceWeather.com said of the solar activity.

But for now, it’s the X-class flare that has everyone’s attention. Generated from sunspot AR2992, we didn’t get the full brunt of the storm as the sunspot was on the extreme edge of the sun during the eruption.

Related: Earth braces for solar storm, potential aurora displays

There’s a chance, however, that coronal mass ejections (CME) of charged particles will from the same site could follow. If a CME happens, auroras might be on the way soon, although scientists aren’t sure yet whether Earth would be in the path of the plasma.

Solar flares have several flavors to them. By category, A-class are weakest and X-class is strongest, with B-, C-, and M-class falling in between in order of strength. With each category, flares are measured by size, with smaller numbers representing smaller flares in that size class. The largest of the overnight flare set was rated X2.2, according to SpaceWeather.

While flares are short outbursts, CMEs can shoot out clumps of charged particles. If the CME is pointed towards Earth, that could cause auroras, the stunning light shows caused by charged particles hitting Earth’s atmosphere. Some circumstantial evidence suggests that is happening already.

“Shortly after the flare, the US Air Force reported a Type II solar radio burst,” SpaceWeather.com explained. “Type II radio bursts are caused by shock waves in the leading edges of CMEs, and this could be a big one.”

The Space Weather Prediction Center at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirmed that the flare occurred at 11:57 p.m. EDT Tuesday (0357 GMT Wednesday) and was accompanied by the Type II outburst.

Scientists will use data from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), a spacecraft operated by NASA and its European counterpart, to monitor for any CME. But the NOAA officials played down the possibility of auroras, given that the originating sunspot was on the extreme edge of the sun.

“As the source region of the flare was beyond the southwest limb, initial analysis suggests any CME is unlikely to have an Earth-directed component,” NOAA stated.

NASA has not provided a detailed forecast yet on the websites for the two spacecraft, nor on social media. “Flares and solar eruptions can impact radio communications, electric power grids, navigation signals, and pose risks to spacecraft and astronauts,” NASA officials wrote in a recent statement.

The sun appears to be waking up in its newest 11-year cycle of solar activity, which began in 2019 and is predicted to peak in 2025. Early in the cycle, scientists forecast that overall the cycle will be quieter than usual given fewer sunspots.

NASA is among a group of space agencies watching the sun from space and on Earth to generate solar weather predictions. CMEs are usually harmless, creating auroras as charged particles hit the magnetic lines of Earth. The most powerful storms, however, may create issues with infrastructure such as satellites or power lines.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.