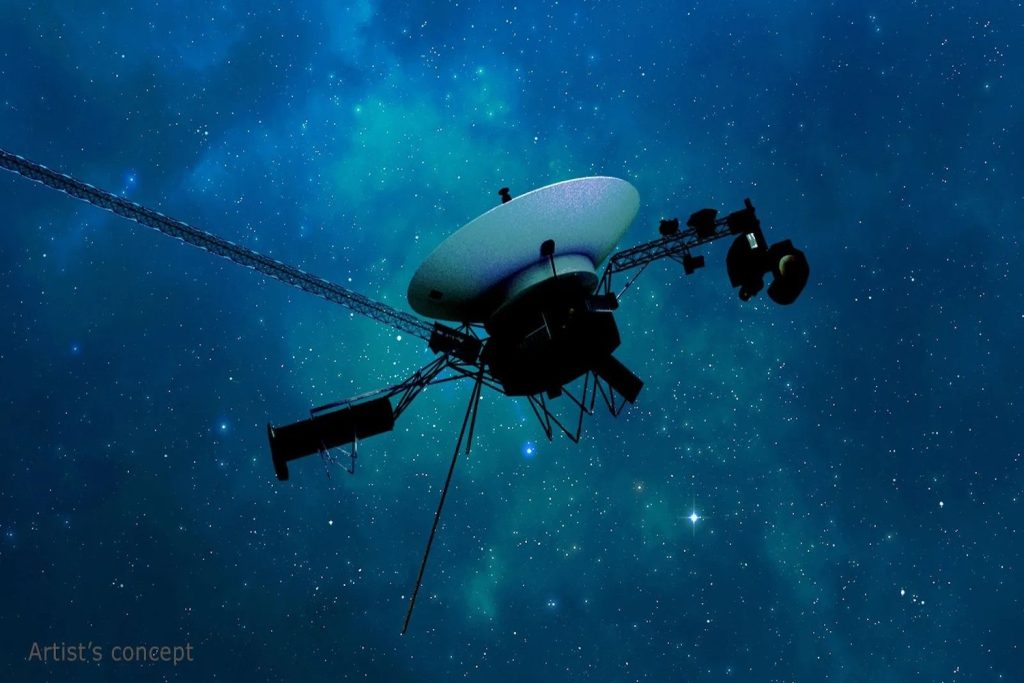

Voyager 1 is currently exploring interstellar space at a distance of 15.5 billion miles (24.9 billion kilometers) away from Earth. Communicating with the farthest human-made object is challenging due to its extremely faint signals, but a telescope designed to detect weak, low-frequency emissions from deep space can still pick them up.

A team of amateur astronomers used the Dwingeloo radio telescope in the Netherlands to receive signals from Voyager 1 after a communication glitch forced the spacecraft to rely on a backup transmitter. Dwingeloo, built in the 1950s, joins an elite group of telescopes able to detect Voyager’s faint radio signals from deep space, a helpful ability when NASA’s antennas, though fully capable, aren’t actively tuned to that frequency.

In late October, Voyager 1 suddenly turned off one of its radio transmitters, forcing the mission team to rely on a backup unit—a weaker transmitter that hadn’t been used since 1981. Voyager’s second radio transmitter, called the S-band, transmits a much fainter signal than its X-band transmitter. The flight team at NASA wasn’t sure the S-band signal could be detected, as the spacecraft is much farther away today than it was 43 years ago. NASA uses the Deep Space Network to communicate with its spacecraft, but the global array of giant radio antennas is optimized for higher frequency signals. Though NASA’s DSN antennas are capable of detecting S-band missives from Voyager—it can also communicate in X-band—the spacecraft’s signal can appear to drop due to how far Voyager is from Earth.

The Dwingeloo telescope, on the other hand, is designed for observing at lower frequencies than the 8.4 gigahertz telemetry transmitted by Voyager 1, according to the C.A. Muller Radio Astronomy Station. Dwingeloo would normally be unable to detect signals being transmitted by Voyager 1, since the mesh of the dish is less reflective at higher frequencies. However, when Voyager 1 switched to a lower frequency, its messages fell within Dwingeloo’s frequency band. Thus, the astronomers took advantage of the spacecraft’s communication glitch to listen in on its faint signals to NASA.

The astronomers used orbital predictions of Voyager 1’s position in space to correct for the Doppler shift in frequency caused by the motion of Earth, as well as the motion of the spacecraft through space. The weak signal was found live, and further analysis later confirmed that it corresponded to the position of Voyager 1.

Thankfully, the mission team at NASA turned Voyager 1’s X-band transmitter back on in November, and is currently carrying out a few remaining tasks to get the spacecraft back to its regular state. Fortunately, radio telescopes like Dwingeloo can help fill in the gaps while NASA’s communications array has trouble reaching its spacecraft.

The iconic Voyager 1 has been feeding scientists with precious data about the solar system and beyond for decades. On its way to interstellar space, the probe had close encounters with Jupiter and Saturn and discovered two Jovian moons, Thebe and Metis, as well as five new moons and a new ring called the G-ring around Saturn.

Clarification: This article has been updated to clarify that the NASA Voyager mission was not affiliated with the Dwingeloo research and to more accurately describe the capabilities of NASA’s Deep Space Network in detecting signals from deep space.