Venus is still alive.

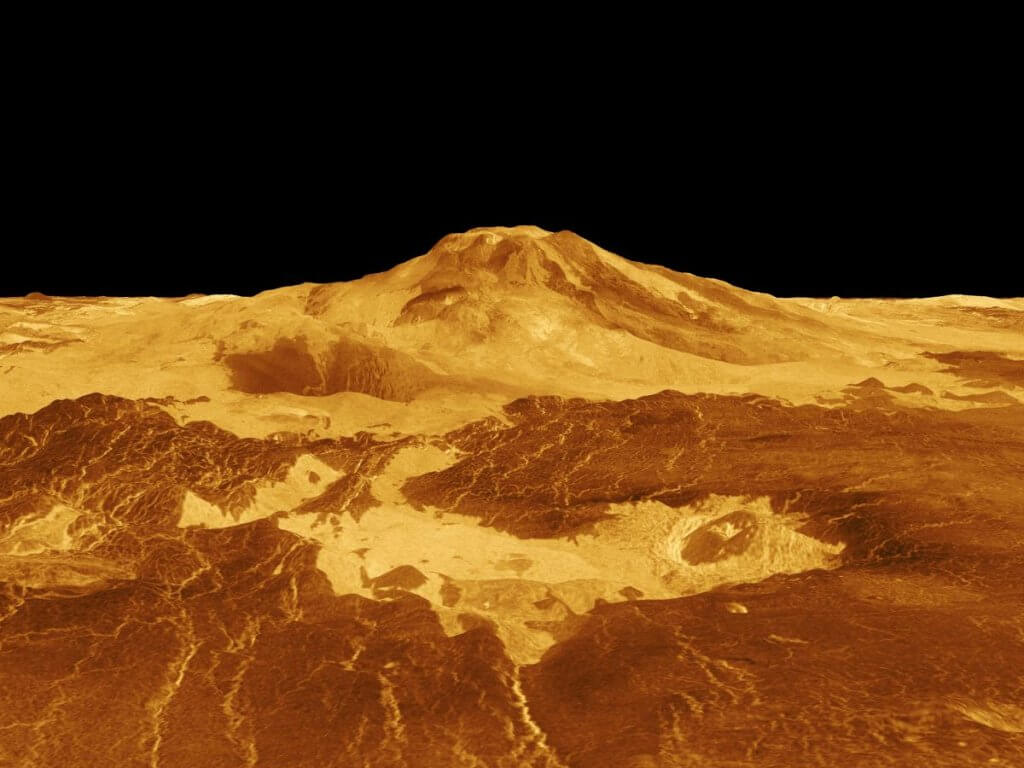

Scientists studying data sent home by NASA’s Magellan spacecraft in the early 1990s say they have spotted volcanic activity on Venus. The discovery, announced in a paper published Wednesday (March 15), is based on changes of a vent near one of the planet’s largest volcanoes, Maat Mons.

“Where we made the discovery is the most likely place that there should have been new volcanism,” Robert Herrick, a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, said Wednesday (March 15) at the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) being held in Texas and virtually.

Related: Planet Venus: 20 interesting facts about the scorching world

Scientists have long known about lava flows on Venus from volcanoes that erupted a few million years ago. Although around 1,600 major volcanoes and close to a million smaller ones dominate the planet’s surface, whether any of them still flare up has been hotly contested.

The latest finding marks the first time that scientists have found direct evidence of recent volcanic activity on the surface of Venus, Earth’s closest neighbor. They think such eruptions — less explosive than those on Earth — occur at least a few times each year, adding to the growing evidence that volcanoes play a major role in shaping the planet’s youthful surface.

In the latest study, scientists analyzed two Magellan images taken eight months apart in 1991. In those eight months, they noticed that a volcanic vent measuring 0.7 square miles (2 square kilometers) grew “considerably larger,” to about 1.5 square miles (4 square km).

Related: 10 incredible volcanoes in our solar system (photos)

They saw that the vent’s shape too had changed: it was circular in the first image, while the second showed it to be kidney-shaped with a dark interior, which is evidence of “a volcano that has erupted on the surface of Venus,” Herrick said during his presentation at LPSC. The dark patch is likely a lava lake filling the vent to its rim, he added.

With the limited data on hand, the team speculates that Venus’ high pressure and blistering temperatures make the lava runnier and flow for longer than it does on Earth.

Venus is overwhelmingly covered with volcanoes, so there are likely many more active ones waiting to be discovered. Herrick said he stopped looking after making the discovery, but “by no means has all the potential searching for new stuff with the Magellan data been done.”

The latest study covers just 1.5% of the planet, while about 40% has been imaged by Magellan twice, giving scientists lots of radar images to sift through.

“There’s still several Hawaii-like volcanoes on Venus that I did not get a chance to search, so there is plenty more to do there,” Herrick said.

Related: Scientists hail ‘the decade of Venus’ with 3 new missions on the way

A discovery from 30-year old data

The Magellan spacecraft arrived at Venus in 1990 and snapped photos from orbit for two years. During this time, the spacecraft revisited the same spots once every eight months. Back then, the purpose of each visit was not to look for changes on the surface like scientists are doing now but to perform various other tasks, so the images ended up being at different angles and heights, Herrick said. Both images pertaining to the discovery could be thought of as being snapped from windows on different sides of a plane, he added.

The first image — taken as if the vent site were seen from a window on the plane’s left side — shows the vent site to be circular in shape. The second image — clicked from a right-side window — shows a kidney-shaped vent with shorter, collapsed walls likely a few hundred feet deep. Herrick also spotted a brighter patch on the ground farther downhill, which he thinks is a new lava flow that poured out of the volcano.

Even though the Magellan images are 30 years old, Herrick attributed the timing of this discovery to recent improvements in software and hardware for planetary scientists. Much like Google Earth, scientists can now easily download large datasets and zoom in and out of radar images, which they couldn’t do three decades ago.

Because Magellan’s images were clicked at different angles, Herrick and his team picked points on the surface of Venus that remained the same in both pictures, and processed them such that they looked as they would if seen from overhead. The process, called orthorectification, helps scientists convert raw images into a format friendly for modeling.

“We really wanted to nail down that the difference we saw in the vent could not possibly, in any way, be a factor of simply looking at the same feature from different angles,” Herrick said during his presentation at LPSC.

Is it really a volcano?

To confirm if what they were seeing was really volcanic activity, Herrick teamed up with Scott Hensley, a project scientist for two of NASA’s upcoming Venus missions.

“I was immediately cautiously optimistic and excited, because it did look real,” Hensley said, adding that previous efforts that looked for similar changes in the images did not lead to positive results. Moreover, many features that did not change on Venus looked different in various Magellan images, thanks to variations in lighting and spacecraft angles.

“We wanted to be very careful here that we really had something,” Hensley said.

So to rule out that the spacecraft angles themselves were responsible for the changes they saw, Hensley used Magellan data about the vent’s shape, depth and other features to simulate hundreds of volcanic vents, 60 of which are outlined in the new paper (opens in new tab), which was published online Wednesday in the journal Science.

“None of our simulations could mimic the kidney shape of the vent,” he said, adding that their simulations also did not show a dark floor throughout the vent spotted by Magellan. “That is what led us to very strongly believe we had a real change on the surface of Venus.”

‘The decade of Venus’ likely to reveal more volcanic activity

In the 2030s, a fleet of spacecraft will visit the planet next door, including NASA’s VERITAS (or Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy) and DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry and Imaging) and Europe’s EnVision.

DAVINCI will send an atmospheric probe into Venus’ clouds, and VERITAS and EnVision will peer through the planet’s thick atmosphere from orbit, looking for miniscule, “centimeter-sized changes” on the planet’s surface — a great deal more than what scientists are able to do with Magellan’s data alone.

“Right now, Magellan is the state of the art,” Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, told reporters at the conference. “That is the highest resolution we have. We really need to get VERITAS and EnVision at Venus in the next decade.”

DAVINCI is slated to lift off in 2029. After a delay that set its launch back by three years, VERITAS is now scheduled to launch between 2032 to 2034, followed closely by EnVision, which will fly between 2035 to 2039. Venus scientists hunting for signs of ongoing volcanic activity are most excited that these new missions will not have the one-sided viewing problem that Magellan did, so future data will be a lot easier to work with, Hensley said.

“It’s going to be a really exciting dataset, and the whole Venus community just can’t wait to get their hands on these data,” he said.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).