The date: July 4, 1054 AD.

At dawn, astronomers in China, and half a world away in what is now the desert southwest of the United States — cave artists of the Anasazi and Mimbres Indian tribes — gazed into the eastern sky. These ancient people all knew the sky; knew each and every star as an old friend. But suddenly here before them — near to a slender waning crescent moon — shone a dazzling star where none had been seen before. And what an amazing star it was!

In terms of brightness, it initially seemed at least several times brighter than Venus and for 23 days was readily visible against a clear, blue daytime sky before it slowly began to fade. For a total of 653 days, it could be seen with the naked eye, before it finally faded completely out of sight. The Chinese called such a star a “guest star,” because it visited for a while and then left.

Fortunately, the men who observed this strange object nearly a millennia ago carefully noted its position in the sky: about two breadths of a full moon northwest of the tip of the star we know as Zeta Tauri, marking the southern horn of Taurus the Bull.

The brilliant planet Jupiter is not far from that spot in the sky right now.

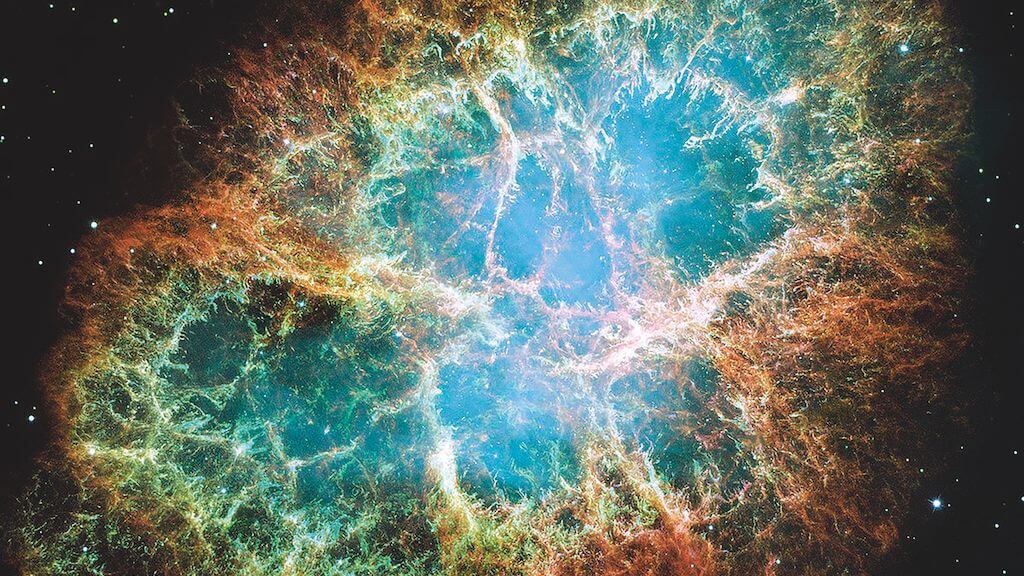

And today when we look at the location of that strange guest star, we see a fuzzy patch of stardust with tentacles of incandescent gas moving rapidly outward in all directions, from where a star had literally blown itself apart.

What a catastrophic explosion this must have been!

Related: Iconic Crab Nebula shines in gorgeous James Webb Space Telescope views (video, image)

A devastating detonation

While some stellar explosions are not very great, this one was absolutely devastating, changing the entire character of the star. Today, we call it a supernova, from the Latin stella nova or “new star.” But far from being a new star, this star had reached the end of its career and would have better been referred to as a dying star.

A typical nova can maintain a tremendous expenditure of energy for a while, after which it fades back to its former obscurity. At the peak of its eruption, the star blows off its outer layers, increasing its brightness by some 50,000 times or more. We have even seen cases of stars that have undergone such contortions more than once.

But there is no second time for a supernova.

In the case of the Guest Star of 1054, a star, at least ten times more massive than our sun, apparently converted the greater part of its mass instantly into radiant energy; the bursting star suddenly flared to a brilliance equal to perhaps 400 billion suns!

Although people here on Earth saw the star blow apart in the year 1054, we now know that it is located about 6,500 light-years from us. So, in reality, this stupendous explosion actually took place around the year 5446 B.C. and then took some 6,300 years for the light from that explosion to finally reach us.

Leftover stardust

In the aftermath, nothing remained, except the intensely hot, newly revealed core of the star and an expanding cloud of gaseous debris, which today we refer to as the Crab Nebula. As of now, the material ejected in the supernova explosion has spread out over a volume of approximately 10 light years in diameter, and incredibly, it’s still expanding outward at a very high velocity of some 1,100 miles (1,800 km) per second.

The first person to see the Crab was an English physician and amateur astronomer, John Bevis in 1731. Then on September 12, 1758, Charles Messier recorded what he described as a

“. . . nebulosity above the southern horn of Taurus . . . it contains no star; it is a whitish light, elongated like the flame of a taper; discovered while observing the comet of 1758.”

It was, in fact, the Crab Nebula’s resemblance to a telescopic comet that prompted Messier to compile his celebrated catalog of such fuzzy objects so that they might not deceive other comet hunters. The Crab Nebula is first on his list and is therefore known as M (Messier) 1. The moniker “Crab Nebula” came about from an 1844 sketch of it made by the English astronomer, the third Earl of Rosse.

Where to find it

To see the Crab Nebula for yourself, you’ll have to wait until around midnight local daylight time, after it has sufficiently risen high enough above the east-northeast horizon. You should also have access to a dark, clear sky, for although relatively bright as planetary nebulas go at visual magnitude +8.4, the Crab unfortunately has a tendency to get lost in the background illumination in light polluted locations.

It may be just barely visible as a rather featureless dim blur of light in good binoculars. It is more readily detectable in a 3-inch telescope and begins to appear as irregularly oval-shaped with telescopes of 6-inch aperture or greater. But to see a few of the scalloped edges; the delicate outer filamentary structure that gave rise to its name, you’ll need a much larger telescope, starting at around 16 inches of aperture. Only then — and only under excellent sky conditions — will hints of the filaments and fine structure of the nebula begin to become visible.

Swiftly whirling

In November 1968, the core of the exploded star which gave rise to the material found in the Crab Nebula was discovered to be a pulsar; a rapidly rotating neutron star, spinning at an incredible rate of some 33 times per second! Apparently, there is a “hot spot” on the star’s surface, which emits energy in virtually every part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Hence as it whirls on its axis it appears to “pulse” from our earthly perspective. This pulsar is but only a fraction of the size of our sun, yet it must be extremely dense in nature; the equivalent of compacting and compressing one solar mass into a volume measuring just 50 miles/30 kilometers in diameter.

Were it somehow possible to transport just a teaspoon of this material to our Earth, it would likely weigh many hundreds of tons!

Still waiting for another

One final point should be mentioned for future reference: the appearance of a spectacular supernova within our galaxy is an exceedingly rare event. In 1987, a naked-eye supernova erupted in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way. Unfortunately, at a distance of 190,000 light years, that supernova appeared no brighter to us than a fourth magnitude star.

But during the past thousand years, there have been four recorded supernovas in our own galaxy that were truly dazzling to the eye. There is a record of a brilliant supernova that appeared in the year 1006 in the constellation of Lupus, the Wolf. Incredibly, that explosion may have even rivaled the one that would appear in 1054.

When and where to look

Another supernova in 1572 flared out in Cassiopeia the Queen and was extensively observed by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. Yet another appeared in the year 1604, this time in the constellation of Ophiuchus, the Serpent Holder. Unfortunately, the appearance of this final supernova occurred just several years before the invention of the telescope. No other such dazzlers have appeared in our sky since. One has to believe that we are long overdue for another.

Perhaps tonight will be that night.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.